Photography and the Smithsonian: the Wonder and Power of the Photographic Image – The Journal of Antiques and Collectibles – June 2004

by Merry Foresta

In December, 2003, Smithsonian Books published a book of photography drawn from the Institute’s vast archives, many never before published. Hundreds of collections were scrutinized, thousands of photographs and negatives examined, hundreds of captions written, generating many absorbing stories in and of themselves. The project took three years to complete; a justified effort; a stunning piece of work.

The Smithsonian, the largest museum complex in the world, holds more than 13 million photographs, housed in nearly 700 special collections and archive centers within its 16 museums and the National Zoo. Its photography archives span nearly 160 years encompassing numerous curators and photographers. Each curator, during their tenure, made choices; to file or discard, pursue or disregard, research or ignore, based on their perception of relevance and importance. Personal judgment was applied to all of the photography collections; photographs of specimens, skeletons, airplane models, geological surveys, planets, plants and animals, and even photographs recording the development of the photographic processes itself.

The Smithsonian was born in 1846, into the midst of the Industrial Age, when the creation of a national museum was signed into law by President James Polk, funded through a bequest from James Smithson, a wealthy British scientist. Although founded as a base for research and scientific expedition, the Smithsonian set out to catalog and organize the world.

Photography emerged at the same time – a time of inventions, and thirst for knowledge of new peoples and places. Its introduction coincided with an explosion in mechanical and technological advances: steam locomotives, sewing machines, the Colt revolver, as well as the cotton gin and reaper, and Morse’s telegraph patent in 1843.

Photography was new and exciting – a true marvel. Newspapers announced it with enthusiasm. Images of intricate detail were nothing less than astonishing. Within a very few years of its announcement in 1839, the populace had seen detailed images of the moon, and bacteria photographed from a microscope.

The Smithsonian itself lost no time in applying the new found tool to its own mission–scientific documentation–in archaeology, anthropology, or geography, biology, or physiology. Photography allowed new options in scientific study. No longer was inspection of a direct object critical for study or comparison purposes. The photograph itself became an object of study. Analysis of the photograph exposed the same enhanced detail available in the laboratory. Similarities and differences could be studied to aid classification and cataloging. Information could be shared over time and distance.

American photographers embraced the initial technology, improved the process, and adopted less expensive procedures. As years passed, the technology was no longer reserved for professional scientists. People learned the trade, invested in equipment, packed their wagons, and sought new markets. Roaming peddlers sold family portraits or likenesses of the son who was heading west, or the sweetheart he was leaving behind.

Portraits were no longer exclusive to the wealthy, but affordable to those of moderate income. Reasonably priced options allowed boys and men going off to the Civil War to leave mementos for mother or sweetheart. As peddlers moved west, they hunted new images – anything exciting and novel to sell to people back home. Far away places were brought to people’s doorsteps; the Grand Canyon, Niagara Falls, American Indians in stunning ceremonial dress.

Postcards

During the second half of the 19th century, and through their heyday before World War I, postcards were abundant, an avenue for photographers to market their work, and for ordinary people to see extraordinary things and places. As early as the 1850s, both American and European photographers traveled to Africa and the Orient, bringing back images of sights only imagined through the art, literature and popular culture of the Victorian age – Egyptian pyramids, Japanese royalty, the Holy Land, African natives.

Into West Africa they traveled, through Liberia and Sierra Leone, where the technology was embraced by local entrepreneurs. Open air studios were assembled; painted backdrops were created showing tropical landscapes, or the architecture and accessories of the wealthy. Patrons were eager to portray themselves as sophisticated, worldly, and important. Color was added by colorists, people who had never seen, first hand, their subjects. What was presented was an image easily interpreted as truth, yet in fact influenced by interpretation and imagination.

Family portraits were quickly in high demand. Earliest portraits were stark and formal – a result of the long exposures necessary. As the technology changed, sitting times were less demanding, children would be included in family portraits, and patrons became conscious of their surroundings. Items placed in a photo were intentional, conveying a sense of identity. Portrait attire became indicative of status; books would speak of intellect and education; dress carefully chosen to be fashionable. The rise of the middle class brought leisure time and disposable income, and folks began to travel to see the country’s natural landmarks. Scores of entrepreneurs set up studios at Niagara Falls, posing visitors and selling stunning souvenir photographs on the spot.

The first major photographic project the Smithsonian Institute embarked upon was the documentation of Indian delegations visiting Washington. Prior to this initiative, more than 150 portraits had been painted of visiting Indian dignitaries. A fire in 1865 destroyed the paintings, and accelerated the proposal to implement photography as a method of record keeping. Photography was less expensive, quicker, less susceptible to the interpretation of the artist, and easily reproduced. By 1867, more than three hundred of these photographs were hung in the newly repaired and renovated Smithsonian building in the Institution’s first exhibition of photographs, Photographic Portraits of North American Indians.

Smithsonian hired its first photographer and photographic curator in 1868, Thomas Smillie. Museum installations were photographed, the Institute’s building projects were documented, and specimens acquired by Smithsonian scientists were photographed and recorded. Smillie clearly understood his role, and that of the new national museum, as a preserver of the past and present, to make it available to the future. Expeditions under Smillie’s charge were equipped with state of the art tools to authenticate their findings. In 1900, he and his assembly of scientists and equipment went to Wadesborough, NC in anticipation of a predicted solar eclipse. Smillie’s goal was to capture the event on film. They were able to rig cameras to seven telescopes and successfully made glass-plate negatives of the eclipse at its peak. The resulting photography was considered an amazing scientific achievement, providing photographic proof of the solar corona.

Whatever the original intent in photographing an individual subject, time and reflection produced differing perspectives; snowflakes were photographed and studied to explore their crystalline characteristics, but the images are stunning in their intricacy and artistic beauty. Exotic animals at the National Zoo were captured on film as modern marvels; today some are sad reminders of animals lost to extinction. Construction projects were recorded for engineering and historic records, but they provide insight into structural principles of the times. In the name of comparative anatomy and physical anthropology, Native Americans and African slaves were photographed to study and compare physical features, results were used in attempts to further the theories of superiority of the “white” race. Hindsight gives us pause at what first was perceived as scientific fact. Today we comprehend more fully that photography, initially celebrated as perfect “truth”, is also, and still, subject to opinion and interpretation, and manipulation by its creator.

Photography and the Smithsonian were invented at the same time, and both were instrumental in revealing the modern world to itself. The Smithsonian holds more than 13 million images spanning over 150 years of taking and collecting photographs. This largely unknown body of photography – most never before published – represents nothing less than the Smithsonian’s effort, in the name of all Americans, to describe and comprehend the world.

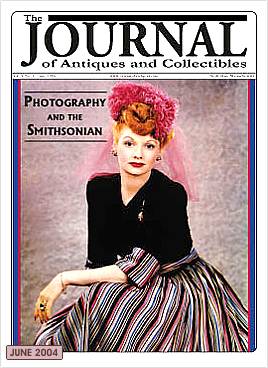

The book is at once a first glimpse at the wealth of photograph holdings at the Smithsonian and an exploration of the wonder and power of the photographic image. Open anywhere in these pages to be plunged in the ongoing history of our modernity, and what the Smithsonian – charged as the nation’s museum – deemed important to document and preserve. The book contains photographs that span the medium’s history and record science, geography, history, the arts, and cultural events, from the first photographs ever made to digital views beamed back from Mars. The famous, the infamous, and the never-before-seen are here in a remarkable “democracy of images”: Amelia Earhart, Abraham Lincoln, P.T. Barnum and Tom Thumb, John Brown, Frederick Douglass, Lucille Ball, Greta Garbo, Babe Ruth; the earliest views of the moon and the earliest panoramic view of Damascus; rare Native American photography; views of Asia, Africa, and the American West; photographs of early flight, and much, much more. By recording the act of seeing, and of what was seen, both photography and the Smithsonian have shaped our sense of ourselves, as individuals, as a people, as a country.

Merry Foresta is senior curator of photography at the Smithsonian Institution. Her previous books include [amazon_link id=”0896598705″ target=”_blank” container=”” container_class=”” ]Perpetual Motif: The Photography of Man Ray[/amazon_link]; [amazon_link id=”0826313639″ target=”_blank” container=”” container_class=”” ]Between Home and Heaven: Contemporary Landscape Photograph[/amazon_link]; and [amazon_link id=”093731126X” target=”_blank” container=”” container_class=”” ]Secrets of the Dark Chamber: The Art of the American Daguerreotype[/amazon_link].

For more information, contact Smithsonian Institution Press at www.sipress.si.edu , call 1-800-233-4830 or contact them via email at info@sipress.edu. All photographs are used with permission of Smithsonian Books.

Related posts: