by Elle Shushan

Adapted from an essay in The Look of Love; Eye Miniatures from the Skier Collection, published by the Birmingham Museum of Art, 2012

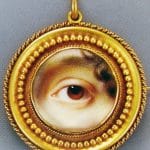

From September 21, 2013, to January 5, 2014, Winterthur hosted the highly successful exhibition titled The Look of Love: Eye Miniatures from the Skier Collection. From the overview of the exhibition: “On loan from the Birmingham Museum of Art, this unique exhibition features hand-painted portraits of individual eyes. The trend for this art form, fragile watercolors on tiny pieces of ivory ensconced in myriad jewelry forms, dates back to the late 18th century and began with a love story.” The companion book to the exhibition bearing the same name included miniature portraitist expert Elle Shushan as a contributor. Here, she shares her insight into many of the gems from the exhibit from the book hailed as “… both fun and has sentiment befitting its subject … ” by Sarah D. Coffin in the American Society of Jewelry Historians Newsletter.

In his comic gem The Four Georges (1860), William Makepeace Thackeray (1811-1863) referred to George IV (George Augustus Frederick, 1762-1830) as “The King of Beasts.”i (Ill. 1) Forty years later, English parodist and caricaturist Sir Max Beerbohm (1872-1956) jumped to the defense of the long-dead and much-maligned monarch, saying Thackeray judged the King “by the moral standard of the Victorian age.”ii He went on to note, “In those days, a young man of wealth and family found open to him a vista of such license as had been unknown to any since the barbatuli of the Roman Empire.”

Indeed, just as the moral pendulum had swung in the four decades between Thackeray and Beerbohm, George IV, in his tenure as the Prince of Wales, ushered in a brief period of indulgence and excess in the upper classes, ripe for the flowering of portraits of illicit loves.

The Sway of the Times

The Prince’s mentor in politics, gambling, and women was the brilliant Whig leader Charles James Fox (1749-1806), who had a pedigree that perfectly illustrated the sway in convention during the 18th century. Fox was the great-grandson of the 1st Duke of Richmond Charles Lennox (1672-1723), whose title was created by King Charles II as he was the illegitimate son of the king and his last mistress, Louise de Keroualle.

Charles Lennox, who was recognized by his Royal father and the Court, amassed an immense fortune built upon lavish gifts from the hedonistic monarch. A solid dynasty was created in a great mansion on the Thames overlooking the King’s Privy Garden. Two generations later, the 2nd Duke of Richmond’s 2nd daughter Lady Sarah Lennox (1745-1826), who was the first great love of King George III, found herself ostracized by society and banned from Court for openly having an affair. Her nephew was Charles James Fox, only four years younger than she but of a different generation. Fox would live with, and then marry the notorious courtesan Elizabeth Armistead, whose affections he originally shared with the Prince of Wales. Of course, the new Mrs. Fox was welcomed at Court.iii

As Beerbohm noted, when the Prince of Wales came of age, “Society broke into a gallop. Great Ladies and courtesans brushed beautiful shoulders in utmost familiarity …”

Artist Richard Cosway

Richard Cosway (1742-1821) was uniquely suited to chronicle this age of unparalleled indulgence. The son of a headmaster in Devon, Cosway’s talent was quickly recognized; he was sent to London at the age of eleven for artistic training. Cosway received the best education, studying with Thomas Hudson at Shipley’s drawing school. By 1760, he was exhibiting at the Society of Artists and, in 1771 after graduating from the Royal Academy Schools, Cosway was elected as a Royal Academician. Cosway, a notorious fop known for his love of design and fashion, married the brilliant and beautiful Anglo-Italian artist Maria Hadfield (who was much admired by Thomas Jefferson), eighteen years his junior, in 1781. They soon hosted one of London’s most cultured and coveted salons.

Considered one of the most important artist-collectors and connoisseurs of the period,iv Cosway quickly attracted the attention of the Prince of Wales. The seventeen-year-old Prince commissioned the fashionable artist to take a miniature of his mistress of the moment, actress Mary Robinson, known as “Perdita.”v By 1780, the Prince was regularly employing (though not payingvi) Cosway.

The twice-widowed Catholic beauty Maria Fitzherbert met the Prince of Wales in 1784.viii Rejecting his determined advances, Mrs. Fitzherbert withdrew to France in the hope that distance would chill the Prince’s infatuation. This had the opposite effect, even eliciting a feigned suicide attempt to attract her attention. The Prince wrote ceaselessly, begging marriage. His letter of November 3, 1785, contained a postscript, saying he was sending a parcel and “at ye. same time and eye, if you have not totally forgotten ye. whole countenance, I think ye. likeness will strike you.”ix

This was the first of two portraits of the Prince’s eye recorded in Cosway’s list of unpaid commissions. Additionally recorded were the notation for the painting of Mrs. Fitzherbert’s eye in 1786 and Cosway’s 1795 portraits of the Prince’s eye and another of his mouth.x

An Earlier French Connection

Jewelry depicting individual eyes have long been popular (the Victoria & Albert Museum in London has Roman and Etruscan examples). In medieval England, there were theological connotations considering eyes to be “the windows of the soul,”xi but the mid-Eighteenth century incarnation almost certainly began in France.

On October 27, 1785, Horace Walpole wrote to the Countess of Ossory, “When human folly, or rather French folly can go so far, it would be trifling to instance a much fainter silliness; but you know Madam, that the fashion now, is it not, to have portraits but of an eye? They say ‘Lord don’t you know it?’ A Frenchman is come over to paint eyes here.”xii

On December 6, 1785, the eccentric Lady Eleanor Butler recorded that a friend, recently returned from the Grand Tour, had brought back “an Eye, done at Paris and Set in a ring; a true French idea and a delightful idea which I admire more than I confess for its singular Beauty and Originality.”xiii

Both of the above letters were written in 1785, prior to the execution of Cosway’s portrait of the Prince’s eye.

There are two even earlier notations: George Engleheart’s fee book lists two

portraits of Mrs. Quarrengton painted in 1783, one of them, her eye.xiv Ten years earlier in 1773, a full twelve years before Cosway took the eye of the Prince of Wales, Oziah Humphry, R.A. (1742-1810) painted two eye miniatures while staying with his patron, the Duke of Dorset, at Knowle.xv The Duke, having strong connections with France, may well have been familiar with the new fashion.

George Engleheart, et al

Richard Cosway and George Engleheart could not have been more different. The flamboyant Cosway was miniaturist to the grandiloquent Prince of Wales. The solid Engleheart served in the same position to the Prince’s Father, the priggish, sober, George III.

One of eight sons born to a German immigrant, George Engleheart (1753-1829) entered the Royal Academy Schools at the age of sixteen. Additionally, Engleheart studied with Sir Joshua Reynolds; he would emerge as one of Reynolds’ most successful copyists.

Engleheart’s production was prolific. His meticulous fee book, which provides the best available record of an artist taking eye portraits, covers the years 1775-1813. 4,853 portraits were documented. Of those, only twenty-two were of eyes.xvi

A quiet, industrious family man, Engleheart was a businessman who kept a busy studio filled with relatives. Both his cousin Thomas Richmond (1771-1837) and his nephew John Cox Dillman (J.C.D.) Engleheart (1782-1862) studied with and then assisted Engleheart before striking out on their own. Thomas Richmond’s work strongly reflected that of his master. Richmond, who exhibited at the Royal Academy from 1795-1829, was retained by the Royal family to copy miniatures by both Engleheart and Cosway.xviii A splendid eye, set in a ring, topped by the coronet of an Earl, may be confidently attributed to him. (Ill. 3).

The exquisite eye of Engleheart’s niece Mary Cox Dillman Engleheart was painted by her brother, J.D.C. Engleheart, circa 1810. (Ill. 4) The nephew, would have had extensive training in the art of eyes. Though there were no other recorded examples of his eye portraits, the discovery of the eye of Engleheart’s sister has facilitated the discovery of others. The splendid diamond-set eye dated 1819 is a stunning example of his mature work. (Ill. 5)

Other Eyes

Very few other Georgian artists were documented as having painted eyes. William Wood (1769-1810) listed one eye miniature in his ledger at the Victoria & Albert Museum, that of Mrs. Oliphant in 1806. Because there is only one recorded, it is safe to assume there were no others. Royal favorite Anthony Stewart (1773-1846) who did a miniature of Princess Victoria at about three years of age, and mezzotint engraver and drawing master William Pether, F.S.A. (1738-1821) known for his engraving of King George III in three different sizes, are known to have painted eyes.

The Scottish National Portrait Gallery has, on long term loan from a private collection, the eye of Princess Charlotte of Wales by Miss Charlotte Jones (1768-1847).xviii A student of Richard Cosway, Jones held the title of miniature painter to H.R.H. Princess Charlotte of Wales (1796-1817), daughter of George IV.

Princess Charlotte of Wales was the unfortunate only child of the Prince of Wales. The only legitimate grandchild of George III (during her lifetime), Charlotte was the hope of a nation ravaged by war with France. Her death during childbirth at the tender age of 21 resulted in massive mourning not seen again until the 1997 death of Diana, Princess of Wales. One of the most elaborate and personal commemorations of Charlotte was the remarkable eye set in the clasp of a bracelet made of the Princess’s hair. (Ill. 6)

In November of 1809, landscape artist John Constable’s (1776-1837) early patron Henry Greswolde Lewis (1754-1829) saw an image of “the human eye & enough of the forehead to know the likeness” in a jewelry shop on Bond Street. Entranced, he requested that Constable paint the eye of his ward to be set in a shirt-pin. If Constable accepted the challenge from Lewis, that eye is now lost.xix

Queen Victoria briefly revived the tradition of eye miniatures early in her reign. The dazzling Sir William Charles Ross, R.A. (1794-1860) held the position of royal miniaturist from the beginning of Queen Victoria’s reign until his death in 1860. Ross painted the majority of those Victoria commissioned. (Ill. 7)

The Queen ordered a number of eye miniatures from Ross, many of which were used as presentation pieces.xx In addition to those of her children, Victoria ordered eyes of friends and relatives including Princess Feodora, the Duke of Coburg, Marie Caroline, Duchesse d’Aumale, and the Duchess of Nemours. Moreover, she retained two artists – Mrs. Dalton (1801-1874, Miss Magdelena Ross, sister of Sir William Charles Ross) and Sicilian artist Guglielmo Faija (1803-1873) to make copies of the Ross originals.xxi

Without a doubt, one of the most spell-binding eye portraits to have been painted was the self-portrait by Dresden artist Gehard von Kugelgen (1772-1820). (Ill. 8) A powerful, direct gaze catches the observer from behind a curtain of cloud. The hypnotic eye, held by a gold and enamel neoclassical frame, is set within the blue glass in a double-sided gold pendant frame. Painted for his wife, the other side holds a profile portrait (interesting that there is no gaze at all) of her father, Wilhelm Zoege von Manteuffel.xxii

Strangely, America, always eager to grab a new fad, did not succumb to the charm of eye miniatures. In 1801, future American superstar artist, miniaturist Edward Greene Malbone (1777-1807) headed off to London at the Royal Academy Schools. Immediately taken with the work of Cosway, Malbone arrived home with inspiration and a new style. During the year after his return, Malbone painted three eyes, two of which are only known today by the copies made by the sitters’ descendent, Revival period miniaturist, Emily Drayton Taylor (1860-1952).

Charleston beauty Maria Miles Heyward sat for Malbone right after his 1801 London sojourn. At the same time, Malbone experimented with the new London fashion, painting her right eye. Emily Heywood Drayton Taylor copied many of her family’s miniatures, including at least three eyes. Both Malbone’s portrait of Maria Heyward’s eye and the Taylor copy are in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.xxiii (Ill. 9a and 9b) The museum holds another Taylor eye, also presumed to be a copy of a Malbone original. Additionally, there is one very similar additional Taylor eye miniature of a different sitter in the Cleveland Museum of Art, also a Malbone copy. Malbone went on, in his short lifetime (he would live only six more years, dying at the age of twenty-nine) to be the finest and most influential miniaturist America would know.xxiv But he painted no more eye miniatures and did not start a fashion. There are only a handful of other eye portraits that can firmly be called American.

But Is It Art

Because there is so little documentary evidence of specific artists rendering eye miniatures, the reasons why must be considered.

Richard Cosway, who famously painted the eyes of both the Prince of Wales in 1785 and Mrs. Fitzherbert in 1786, returned to the form only once in 1795. Cosway again took a portrait of the Prince’s Eye.xxv During his years as Royal Miniaturist, Cosway did not invoice the Prince for the massive amount of work ordered and executed, instead of enjoying the access and patronage afforded his position as Royal Miniaturist. Therefore, all work performed for the Prince appeared in Cosway’s list of unpaid commissions. Despite the fame he garnered by having created the first two miniatures, it is highly unlikely that he painted any other eye portraits.xxvi During his entire career, Cosway carefully managed his image and position as an artist. It is apparent that he considered the form somewhat beneath art and therefore not worthy.

George Engleheart, the businessman who accepted the commissions offered to him, failed to display a single eye portrait during the forty-nine years he exhibited at the Royal Academy.

The indication is that eye portraits were, in fact, not considered fine art. It is probable that they were a hybrid – part portrait, part jewelry, part decoration, the vast majority executed by many technically competent, unknown workmen artists.

These eyes, most ad vivum, were referred to as “trinkets” by some as they were framed in jewel-set rings, (Ill. 10) bracelet clasps, (Ill. 11) and brooches. (Ill. 12) They were set in canes and snuff boxes, commemorating not only love, but friendship, family, and death.xxvii

In the 226 years since the great love story of the Prince of Wales and Mrs. Fitzherbert turned the implication of eye portraits into the subject of gossip and speculation, they have been the most desired and coveted of miniatures, evoking immense emotion. The significance of the artist diminishes next to the significance of the power of the portrait – which was exactly the reaction the Prince had hoped for.

The Artist’s Eye

Photos courtesy: William Grimaldi; Collection of Dr. & Mrs. David Skier; Christie’s, London; Collection of Dr. & Mrs. David Skier; The Royal Collection© 2011; Dorothee von Hellermann; Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource, NY; Private Collections

i Thackeray, The Four Georges, Sketches of Manners, Morals, Court and Town Life, London, 1861, based on a series of lectures given in the late 1850s.

ii Beerbohm, “King George the Fourth,” The Works of Max Beerbohm, London 1894.

iii For an absorbing account of this remarkable family, see Tillyard, Aristocrats: Caroline, Emily, Louisa, and Sarah Lennox, 1740-1832, London, Chatto & Windus Ltd., 1994.

iv Lloyd, Richard, and Maria Cosway: Regency Artists of Taste and Fashion, Edinburgh, Scottish National Portrait Gallery, 1995, p. 14.

v Munson, Maria Fitzherbert: The Secret Wife of George IV, New York, 2002, p. 66.

vi Lloyd, “The Cosway Inventory of 1820: Listing Unpaid Commissions and the Contents of 20 Stratford Place, Oxford Street, London,” The Walpole Society, vol. 66, p. 196.

vii Lloyd, Richard, and Maria Cosway: Regency Artists of Taste and Fashion, Edinburgh, Scottish National Portrait Gallery, 1995, p.14.

viii Munson, Maria Fitzherbert: the Secret Wife of George IV, New York, 2002, p. 75.

ix Munson, Maria Fitzherbert: the Secret Wife of George IV, New York, 2002, p. 140.

x Lloyd, “The Cosway Inventory of 1820: Listing Unpaid Commissions and the Contents of 20 Stratford Place, Oxford Street, London,”

xi Lloyd and Remington, Masterpieces in Little: Portrait Miniatures from the Collection of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, London, Royal Collection Enterprises Limited, 1996, p. 41.

xii Cunningham, editor, The Letters of Horace Walpole, Fourth Earl of Oxford, London, Richard Bentley and Son, 1891, vol. 9, p. 26.

xiii Bell, G.H., editor, The Hamwood Papers of the Ladies of Llangollen and Caroline Hamilton, London, Macmillan, 1930, p. 65.

xiv Williamson and Engleheart, George Engleheart 1750-1829: Miniature Painter to George III, London, privately printed, 1902, p.110.

xv Williamson, G.C., “Miniature Paintings of Eyes,” The Connoisseur, X, September-December, 1904, p. 147.

xvi The fee book is reproduced in Williamson and Engleheart, George Engleheart 1750-1829

xvii Foskett, D., Miniatures, Dictionary and Guide, London, 1987, Antique Collector’s Club Ltd., p.627.

xviii Lloyd, Portrait Miniatures from the National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, 2004, National Galleries of Scotland, p. 97, no. 79.

xix Gayford & Lyles, Constable Portraits: The Painter and his Circle, London, 2009, National Portrait Gallery, p. 104.

xx Remington, Victorian Miniatures in the Collection of Her Majesty The Queen, London, 2010, Royal Collection Publications, vol. II, p. 432.

xxi Remington, Victorian Miniatures in the Collection of Her Majesty The Queen, London, 2010, Royal Collection Publications, vol. II, pgs. 432 and 565.

xxii Hellermann, Gerhard von Kugelgen (1772-1820), Das zeichnerische und malerische Werk, Berlin, 2001, Dietrich Reimer Verlag, color plate XI, no pl. 104a, 104b.

xxiii Barratt and Zabar, American Portrait Miniatures in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2010, p. 95, no. 181, for the eye of Maria Heyward, p. 237, nos. 472, 473 for the Taylor copies.

xxiv For a discussion of Malbone’s career and his influence on American portrait miniatures, see: Shushan, “How America Found Her Face,” The Magazine Antiques, vol CLXXV, no. 4, April 2009

pp. 68-75.

xxv Lloyd, “The Cosway Inventory of 1820: Listing Unpaid Commissions and the Contents of 20 Stratford Place, Oxford Street, London,” The Walpole Society, 2004, vol. 66, p. 197.

xxvi Related in conversation with Dr. Stephen Lloyd.

xxvii Grootenboer, “Treasuring the Gaze: Eye Miniature Portraits and the Intimacy of Vision,” Art Bulletin 88, 2006, p. 496.

Related posts: