The Mini Time Machine Museum Collection

The Mini Time Machine Museum of Miniatures is dedicated to sharing the wonder of miniatures and inspiring new audiences to cherish and appreciate this universal art form. The museum was created from the imagination and dedication of Founders Patricia and Walter Arnell. Mrs. Arnell’s fondness for miniatures began in the 1930s when as a young girl she received her first miniatures – a set of Strombecker wooden dollhouse furniture. The beloved tiny furniture stayed with Mrs. Arnell, safely packed away for decades. It wouldn’t be until the Arnells moved to Tucson in the late 1970s that she rediscovered these treasured toys – and was once again inspired by them. Seeking a dollhouse for the Strombecker set, Mrs. Arnell headed to an antique store and found a Schoenhut dollhouse seemingly the same as her original childhood toy. Furnishing the small house prompted a passion for miniatures that grew into a collection of over 375 antique and contemporary dollhouses, fine-scale miniature buildings, roomboxes, and vignettes.

As the collection grew, Mrs. Arnell and her husband began to dream of a way to share it. They envisioned an interactive and enchanting space, providing a rich sensory experience to visitors. In 2006, The Mini Time Machine Museum of Miniatures was incorporated as a 501(c)3 nonprofit, with the museum opening to the public on September 1, 2009. The mission driving the museum’s programming, acquisitions, and collection care is to preserve and advance the art of miniatures.

A Flourishing Collection

Through a combination of purchases and generous gifts, the museum’s collection has flourished, currently encompassing over 500 pieces including 60 antiques. The antiques inspired the museum’s name, as they seemingly transport us back in time, allowing us to imagine how life was lived hundreds of years ago. We learn who uses miniatures, what purposes they serve, and how the world and the role of miniatures have changed over time throughout various cultures and regions.

One of the first pieces you encounter in the History Gallery is Daneway House, ca. 1775. This George III style “baby house” was made in England and is a typical example from the period. The term “baby house” does not mean it was a toy for children; rather, it refers to the petite size of the furnishings. It was created as a showpiece for the Lady of the house and would be considered part of the family’s art collection. The baby house is well appointed with dolls, furniture, and accessories that likely replicated objects in the Lady’s actual home. Of special note is a complete set of Shakespeare’s plays, printed in books no more than 2 inches tall.

When acquired, Daneway House was fitted with a plywood facade, clearly not original. Numerous coats of paint—the last one bright pink—hid the original stained wood. Mrs. Arnell hired miniaturist Casey Rice to restore the baby house. Ms. Rice was fortunate to have access to photographs of the house as it looked over 30 years prior, helping to clarify its long history of modifications and “makeovers.” She stripped away the paint and other historically unacceptable details including large lights thrust through holes cut into the sides. She researched and designed an architecturally appropriate facade, which

Mrs. Arnell then had custom-built and fitted to the house. The restoration effort took a year to complete, returning the piece to a condition which more accurately reflects its original grandeur from well-over 200 years ago.

The Nuremberg Kitchen

The oldest piece in the collection is the 18th Century Nuremberg Kitchen, dated on the chimney to 1742. Especially popular in Germany, toy kitchens resembling real kitchens in South Germany were known as the “Nuremberg” style. Like its real-world counterpart, this Nuremberg kitchen has a central cooking area with an overhead flue, rows of shelves for displaying plates, a checked pattern floor, and a poultry pen. It duplicates a kitchen in an early Georg Bestelmeier catalog: in his 1798 volume, the Nuremberg merchant lists over 8,000 toys and educational materials, including fully furnished doll’s houses and kitchens. In 1742, a kitchen such as this would have been affordable only to wealthy households.

Mass Production

The Industrial Revolution opened the doors of mass-production for the toy industry, developing first in Germany and spreading across Europe and into the United States, bringing dollhouses to the masses. The museum owns another Nuremberg kitchen designed and built by the Moritz Gottschalk Company around 1909. The Gottschalk Company located in Marienberg, Saxony produced toys for over seven decades, dominating the dollhouse market from 1880 to the 1930s when WWII changed toy production in Germany forever.

The museum’s Gottschalk piece shows the change in real-world Nuremberg kitchens at the turn-of-the-century. Unlike the earlier dark, sooty style, kitchens from this period generally had cream or white lacquered furniture and Delft tiled walls. Lithographed paper is used to imitate the bright and clean tile. Young girls were encouraged to practice their chores while at play; a tank on the back of the wall holds water for the faucet, so children could wash both the room and the dishes. Brooms, hand brushes, and dustpans sold as sets, and rendered the tools young girls needed to keep their kitchen spick and span.

Metal cookstoves were popular appliances in toy kitchens. The stove in this toy was heated with candles and a bucket was provided to empty debris when finished cooking. Mrs. Arnell found candle stubs inside the stove when she acquired the piece. The miniature coffee and meat grinder, with its small handles that turn and compartments that open, could actually grind soft bits of oatmeal.

Bliss Manufacturing Company

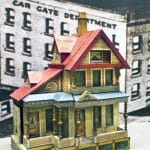

Bliss Manufacturing Co., located in Pawtucket, Rhode Island made many products in their 100-year history, but they are best known for their wooden toys and dollhouses covered with colorful lithographed paper. While the exact date which they began manufacturing toys is not known, the earliest known advertisement for Bliss toys appeared in 1871. In addition to dollhouses, they produced lithographed blocks, pull toys, games, and even tiny pianos and tool chests for lucky children.

Bliss dollhouses were simply constructed, usually with only a few rooms and designed in late-Victorian style, their shapes and sizes enhanced by fancy gables and dormers, porches, balconies, posts, and pillars. Some houses had hinged doors and cutout windows, lined with Isinglass and lace curtains. The architectural details of a Bliss house are depicted through the lithographed paper which covered the exterior: elaborate trimmings, railings, and sidings were printed in wonderfully rich colors that have remained relatively vibrant over time. The interiors were often decorated with lithographed wallpaper, floor coverings, windows, doors, and other interior details, but not nearly as elaborate as the exterior designs.

Bliss houses came in a range of sizes and corresponding price points to meet every budget, from a simple two-room folding house that stands 10” tall, to a wonderfully elaborate large house with two stories and an attic measuring 24” tall. In addition to houses, Bliss created firehouses, garages, and stables so a child could potentially assemble a village.

Related Miniatures

The museum’s collection of antiques also includes miniature mechanical parlor toys with wind-up mechanisms that bring them to life. People of means might have owned a miniature mechanical house depicting daily life or gave their child whimsical toys with moving parts such as the French Schoolhouse in the museum’s collection. Miniature mechanical toys, wound or cranked into motion by an adult or child, allowed the player to imagine and muse about life whilst watching the action unfold. The French Schoolhouse features a music cylinder that plays a tune while the teacher sways back and forth with pointer extended, guiding the children in their lesson.

Alongside the French Schoolhouse, the museum owns a mechanical house created by Emil Wick of Switzerland. The house is one of five created for his five godchildren, each unique, and an extraordinary living document of early 19th century Swiss village life. The museum’s enchanting automated three-story wooden hotel, typical of Basel, Switzerland in the early 1800s, is populated with mechanical figures animated by a key-wound and weight-driven mechanism. Inside the cabinet base is a music cylinder that chimes two different tunes. Though almost certainly influenced by the Swiss tradition of elegant clock making, Wick’s engineering is delightfully chaotic. The inner workings of this house are a web of strings, pulleys, wires, and cams set in motion by the descent of a carefully balanced weight. Despite their jumbled appearance, Wick’s mechanics yield surprisingly sophisticated animation. There are over 30 different movements, some of them remarkably complex. The dancers on the upper balcony, for example, don’t just spin randomly, but pause and pirouette in step with a stately waltz. Wick modeled all his figures on people he knew. Though simply carved, each one is individually detailed, and no doubt would have been recognizable to Wick’s family and friends.

The Automata House

The museum acquired a unique Automata House in 2017, created by an unknown artisan, possibly American, around 1860-1930. This piece may have been a limited-edition toy or a one-of-a-kind folk-art tableau. Victorian paper scraps mounted on wood surround the building. They depict villagers dressed in clothing reminiscent of mid-19th century rural America, and farm animals, including two domestic turkeys, native to North America. Powered by a hand crank with a mainspring, it is possible this machine was clockwork-driven. Evidence of an original clockwork mechanism exists in the form of an on/off switch, brass gearing, and a ratchet and pawl.

Just Suits

Another rare piece in the collection is a spectacular miniature house known as Just Suits, built in Malden, Massachusetts around 1900. Dozens of wooden cigar boxes were used to construct the house. When wooden boxes became the standard for cigars in the 1850s, they became a popular resource for folk artists and craftsmen of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Although aromatic cedar was the most popular type of wood for cigar packaging, the boxes crafted into the walls and shingles of this house were made of walnut. The builder might have favored the Just Suits brand, as the remnant of a box of Just Suits launderette cigars was found in the miniature’s attic. Stamped logos identifying the Buchanan & Lyall tobacco company are still visible beneath the attic roof.

According to the popular lore accompanying this miniature, the builder died soon after completing it – the victim of an accident involving an unlucky encounter with a horse-drawn buggy. The owners of the house commemorated his passing by adding figures of a skeleton leaning against a lamppost and a devil riding a velocipede. A small buggy, sans-horse, completed the memorial.

And There’s More

This is just a snapshot of a few of the antique miniatures presented within The Mini Time Machine Museum’s permanent collection. From January 28 to April 19, 2020, the Museum will present Global Miniatures, an exhibit of tiny artifacts dating from ancient to contemporary times, representing cultures around the world, including the Americas, Asia, Africa, Europe, and the Pacific Islands, on loan from the Fleming Museum of Art, University of Vermont. If you are in Tucson, plan to schedule a visit.

Great Collections: November 2019

Photo’s by Amy Haskell, Balfour Walker, Michael Shea Muscarello, courtesy of The Mini Time Machine Museum of Miniatures.

Related posts: