Original Article:

Life Rolls on at the National Museum of Roller Skating – The Journal of Antiques and Collectibles – September 2012

Updated June 2025:

Since 2012, the National Museum of Roller Skating in Lincoln, Nebraska, has introduced several exciting exhibits and initiatives that celebrate the rich history and evolving culture of roller skating. These additions offer visitors a deeper insight into the sport’s impact on society and its various competitive forms.

Competition: Spirit of the Sport

This permanent exhibit delves into the diverse world of roller skating competitions, highlighting disciplines such as hockey, speed skating, roller derby, and artistic skating. It showcases the dedication and achievements of athletes like Fred Murree, Gene Murray, Tara Lipinski, Apolo Ohno, and Erin Jackson. Notably, the exhibit is being updated to include “Culture Roll,” a new sport established in 2021 by Reggie “Premier” Brown and Darius “D-Breez” Stroud.

Pop Culture: Society and Roller Skating

Exploring the intersection of roller skating and popular culture, this exhibit illustrates how skating has influenced and been influenced by movies, comics, and music from the early 1900s to the present. It offers a unique perspective on how roller skating reflects societal trends and artistic expressions.

Audio Tour Experience

The museum launched a comprehensive audio tour in 2022 to enhance visitor engagement. This self-guided experience covers various facets of roller skating history, including its origins, cultural significance, and competitive aspects. Topics range from the first roller skates and the disco era to the emergence of jam skating and roller skating’s role in wartime efforts.

The “Newest” Craze Exhibit

Reflecting on the resurgence of roller skating’s popularity, this exhibit examines five distinct periods when skating captivated the public’s imagination.

It provides insights into the factors contributing to these booms, including the recent revival fueled by social media platforms like TikTok.

Oral History Project

The museum’s ongoing Oral History Project aims to preserve personal stories and experiences from the roller skating community. The project enriches the museum’s narrative by collecting interviews and firsthand accounts and ensures that diverse voices within the skating world are heard and remembered.

These developments underscore the National Museum of Roller Skating’s commitment to celebrating the sport’s legacy and dynamic role in culture and society. Visitors are encouraged to explore these exhibits and participate in the museum’s initiatives to comprehensively understand roller skating’s past, present, and future.

For more information on current exhibits and visiting hours, please visit the museum’s website: www.rollerskatingmuseum.org.

Original Article:

Life Rolls on at the National Museum of Roller Skating – The Journal of Antiques and Collectibles – September 2012

by James Vannurden

National Museum of Roller Skating

The National Museum of Roller Skating located in Lincoln, Nebraska, houses the largest collection of roller skates and roller skating memorabilia in the country. Visitors know it is the premier organization for roller skating and donations, and are confident their personal collections are stored to the highest quality. After over 30 years of existence, the National Museum of Roller Skating can accurately accept its place as the top roller skating museum in the world.

The story of roller skating begins in the 1760s. John Joseph Merlin, an instrument maker by trade, also tinkered with improving existing ideas and even creating his own. Merlin is credited with the first official documented use of a roller skate. Invited to a masquerade ball in London, Merlin decided to make a grand entrance. While playing a handmade violin, Merlin sailed into the party on his new invention, the roller skate. Being inexperienced as a skater, Merlin crashed into a large mirror, shattered it to pieces, cutting up his body, and making a fool of himself. This was the official introduction of roller skating to the world. The negative perception lingered for years and skating was forgotten. That was until about 1820 in Paris.

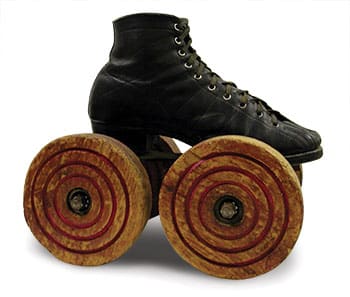

By the early 1800s, the world was again ready for the roller skate. With the popularity of ice skating, participants wanted the experience year round. So Monsieur Petitbled of Paris patented the first roller skate. A three-wheeled inline, the first skate was constructed of wood and included straps to fasten them to the skater’s feet. The wheels came in three possible materials: wood, metal, or ivory. Without a brake, the new Petitbled skate best simulated ice skating on non-ice surfaces. However, the one major complaint with this skate and other early roller skates encompassed the idea that turning corners proved difficult. One had to constantly pick up the feet to change directions, and this became a problem for those with limited skating experience. So after the introduction of the Petitbled, others embarked on creating better roller skating for the masses. It is with this skate where the collection of the museum starts.

The museum begins with early roller skating, pre 1860s. Many early models are housed in the museum, beginning with the Petitbled skate. The Volito skate of 1823 from England showcased the first use of a braking system, with a simple hook attached to the toe of the skate; this rudimentary idea later expanded to the toe stops of today. The French “Cingar” skate of 1828 expanded on the brake system by adding a rear brake. To simulate ice skating on the stage, Le Grande developed his skate to look like an ice skate for stage use in the opera “Le Prophete” in 1849; the popularity of this opera sparked interest in the sport of roller skating. The “Woodward” of 1859 used rubber wheels for added traction and slightly increased the size of the inner wheel to allow for a pivot action to shift directions. Stamped “Feb 24, 1860” the next skate also used rubber wheels but attached them to a steel plate. A two-wheeled skate patented by Albert Anderson in November of 1861 had a rather large wheel in the front to better roll over obstacles, and a much smaller wheel in the back for steering.

In 1863, the whole format of roller skating changed forever with the new invention of an American. James Plimpton from Massachusetts changed skating forever with his 1863 invention. Doctor recommend, he began roller skating for physical therapy. Shortly after his initial skate, Plimpton realized how difficult it was to control the best skates of the day and perform the same types of turns available on ice skates. He then put it upon himself to improve the act of roller skating. After studying many types of skates, Plimpton created his own – a quad skate. Known as the “rocking action” skate, Plimpton attached the wheels to rubber blocks instead of the plate itself; this allowed the skater to round corners simply by shifting body weight side to side. The quad design also gave skaters better balance. With the introduction of the Plimpton model, interest in roller skating skyrocketed. The children of Presidents like Jimmy Carter, Teddy Roosevelt, James Garfield, and Gerald Ford even had fun roller skating around the White House. With its new found popularity, Plimpton later opened the first public roller skating rink, located in Newport, Rhode Island.

After the introduction of Plimpton’s skates, many others began surfacing. In 1869 AJ Gibson patented a combination skate; three rollers could be removed and an ice blade added to one pair of skates, usable on both surfaces. Hiram Robbins patented his skate in 1870 in which he connected the rollers using levers underneath the plate that could turn directions when applied with foot pressure. The John Lemman skate of 1870 connected the wheels to the plate using a ball and socket joint. John L. Boone’s “Spring Skate” of 1871 used spring pressure to shift directions, a similar idea that was used by Cyrus W. Saladee in his skate from 1876. One of the most unusual truck assemblies in the museum belongs to the “Rariai” skate from Sheffield, England. This two-wheeled skate has a spring on either side of each wheel to resemble the rocking motion. Each of these skates is housed within the museum collection.

In addition to these individual skates, manufacturing companies began opening in the United States with the sole purpose of constructing roller skates. The Samuel Winslow Skate Company of Massachusetts opened in the 1870s; their “Vineyard” model line became the most popular skate produced during the 1880s. The Barney and Berry Skate Company patented the use of clamp-on attachment to skaters shoes while other manufacturers had to use straps; better known for ice skates, the company lasted from 1865 until 1923. Union Hardware opened in the early 1870s and continued manufacturing skates under different ownerships for 100 years. Founded in 1880 the Henley Skate Company of Indiana introduced the “kingbolt” which made skate cushion tension adjustable; their trademark curved plate skate was adopted by the National Museum of Roller Skating for its official logo.

The Richardson Ball Bearing Skate company introduced the first steel ball bearings in wheels in 1884. The final large American company to open its doors was the Chicago Roller Skate Company; the dominate manufacturer of the 20th century, Chicago skates are still available today. Examples from all of these companies are on permanent display at the museum.

Also on permanent display is our “odd and unusual skates” display. Here the museum includes strange and bizarre items, including a stilt skate. There are two motorized skates; the first has an engine that straps to your back and propels the skater up to 40mph while the other has a chainsaw motor attached to the toe and travels 30mph. One skate has an odometer. Another has support planks that attach below the knee to give the skater more ankle security. Two skates have spherical wheels. Also showcased are skates for a horse, a bear, and a parakeet.

Photography of Roller Skates & Roller Skating

Paired with all of the skates is the wonderful photographic collection. Each display consists of many of these photos to help illustrate the story. Photos date back to the early 1800s as well as illustrations from early magazines such as the New Yorker. Early rinks are portrayed such as a tent rink from 1924 blown up to a large size. Couples skating saturate the gallery and also spill onto the painting collection. A roller basketball team from 1922, a Halloween party in 1937, roller derby images from the 1940s, and championship matches in figure skating from the 1950s, dot the exhibits. Vaudeville act pictures from the early 1900s sit near the Skating Vanities traveling roller skating show of the 1940s and 1950s. Speed skating troops from 1913, 1915, and 1920 showcase early speed racing. Roller derby in the 1950s exemplifies the popularity of the sport. Roller hockey from the 1920s showcases the primitive nature of its equipment and uniforms. Along with the thousands of photographs not on display in the archives, these roller skating photos portray the sport in ways words cannot.

In addition to the photographs, costumes line the display gallery as well. A chronological display showcases figure skating costumes starting in the 1950s and travels through the present. There are speed skating uniforms from 1907 and 1966 displayed. Roller hockey jerseys of today are paired with roller hockey outfits from the 1960s. A dress from headliner Gloria Nord highlights a display on the traveling roller skating show of the 1940s known as the Skating Vanities. Miss Arizona 1989 roller skated to “Amazing Grace” during the talent portion of the Miss America pageant; the outfit she wore is on display at the museum. Tara Lipinski, former Olympic Gold medalist in ice skating, began her career on roller skates; her national championship winning costume from 1991 hangs on permanent display.

While costumes, photographs, and skates are the main items showcased in the museum, other pieces help bring alive the idea of roller skating to visitors. There are six paintings showcasing skating couples. Also shown is an original 1870s lithograph from Jules Cheret, known as the father of poster art, depicting a Parisian roller rink. Skate boxes and trophies line the tops of each display cabinet. The archival room houses complete collections of many roller skating magazines and newspapers; it also includes books, rink stickers, patent papers, programs, medals, postcards, board meeting minutes, posters, patches, and toys. The USA Roller Sports Hall of Fame lines the entrance to the museum and features athletes, coaches, and distinguished service members.

With over 200 years of history, the National Museum of Roller Skating reminds everyone of a great American pastime. For more information visit www.rollerskatingmuseum.com.

Related posts: