By Melody Amsel-Arieli

During the Middle Ages, Europeans grieved the passing of loved ones by following a variety of traditional social and religious rituals. Since lives then were marked by disease and high childhood mortality, scores of mourners wore death-themed memento mori “remember you must die” rings, pendants, lockets, and brooches depicting coffins, skulls, skeletons, and coffins. Rather than celebrate Death, these were considered reminders to cherish each waking day.

The Popularity of Mourning Jewelry

Eventually, upper-class bereaved families, swept by tradition and sentimentality, offered mourners memento mori-type pieces, holding bits of hair of the departed, for comfort and consolation. Since people believed that human hair contains the essence of an individual, this was neither strange nor shocking. Indeed, through generations, the pious had venerated the locks of saints and lovers had exchanged plaited locks as personal keepsakes.

Mourning jewelry linked to specific losses became popular. However, only after the controversial execution of Charles I in 1649. Loyal Stuart supporters not only commissioned rings, earrings, brooches, and lockets bearing miniatures of his image with the inscription “The glory of England has departed.” They also treasured “Stuart Crystals,” flat-topped carved rock crystal quartz tributes featuring golden crowns or the King’s initials arranged atop locks of his hair.

By the turn of the century, funerals had become increasingly extravagant. In fact, mourning rings, depicting coffins, funeral urns, serpents, and seed pearl “tears” alongside engraved facts about the deceased, are post-mortem status symbols. Samuel Pepys, an English diarist and naval official, for example, willed that, at his death, mourning rings be presented to over a hundred relatives, servants, dependents, domestics, academics, naval officers, gentlemen, members of the clergy, and others. What began as a simple way of memorializing a loved one had become a funereal art practiced by many.

During the Georgian era, gold mourning rings, signifying the eternal nature of the soul through life and death, often replicated snakes clasping their tails in their mouths. Some inscribed, urn-themed models swiveled against their wearer’s skin to hide their personal

significance, while others featured bold black enamel bands, rich brocade detail, compartments for locks of the deceased, and inscriptions like “Sarah Reeves died March 12, 1823, aged 81 years” in ornate gold gothic lettering.

Hair as the Essence of Life

Human hair, as a major component of jewelry, appeared first in early 19th-century Sweden. Facing poverty, inhospitable weather, and a dearth of farmland for its growing population, enterprising Swedish women devised a method of braiding and weaving their most abundant resource, their gloriously long hair, into decorative brooches, hat pins, and crosses. Then, as a viable cottage industry emerged, they fanned out across northern Europe, hawking their wares.

By the early 19th century, human hair had become a highly desirable artistic medium. Yet even modest pieces of jewelry, due to the intricacy of their designs, required great amounts. So, each spring, merchants fanned out to fairs and markets that dotted Europe, enticing maidens by offering trinkets and trifles in exchange for their lengthy tresses.

The Victorian State of Mourning

Many hair brooches, rings, and earrings were featured at England’s 1853 Crystal Palace Exposition. This art form was popularized in 1861 however, after Queen Victoria, at the sudden loss of her husband Prince Albert, embellished her black crepe widow’s weeds with a variety of appropriate somber accessories.

Queen Victoria also wore a specific, fine-quality jet called Whitby jet as part of her mourning dress after Prince Albert’s passing. Deposits of Whitby jet are seen as narrow planks in the cliffs along a 7.5-mile stretch of North Yorkshire coastline, where Whitby is located. Famed for its deep, intense black color and the lustrous shine that can be achieved by polishing it. It is also very light in weight making it perfect for jewelry.

Bereaved commoners soon followed suit. Some exchanged bright pearls for strands of dark, hair-wrapped or Whitby jet beads. Some wore delicate jet brooches or bore bracelets a-dangle with heavy hair work crosses. Others accessorized their full, second, and half-mourning apparel with brooches featuring designs fashioned from locks of the dear departed.

Refining the Craft

Though these were processed in a variety of ways, braided or woven patterns were the most popular. To create them, swaths of perfectly straight, combed hair were boiled in soda water, sorted into appropriate lengths, then divided into remarkably slender bundles. These were positioned on special tables fitted with tiny weights and bobbins which, when manipulated, worked them into braids and patterns. After coaxing these round ready-made molds, boiling, and drying, they were unmolded. Then they were sent to jewelers for mounting in oval or round decorative cases. Some were simple hair-holding containers featuring removable tops. Others, like cases, featured more durable, glassed-in locks.

Palette-work, another hair work technique, was created by stiffening strands with egg white, carefully combing them in one direction then gluing them to a flat surface. When dried, these were cut into exceedingly small segments, formed into delicate textured patterns, then mounted in jewelry casings. Other strands were fanned into fashionable, feathery “Prince of Wales” designs or curled like the one inscribed “In Memory Of R. Burton Sept. 2, 1855 and E. Burton Oct. 27, 1865 husband and wife.”

“Sepia” mourning pieces were created by chopping, snipping, or grinding bits of hair until completely pulverized into powder. This was mixed with sepia, brown ink derived from cuttlefish. Then artists used this curious concoction to paint miniature mourning scenes of funeral urns, weeping willows, or grief-stricken widows leaning against tombs on palette-worked grounds. Some featured Prince-of-Wales hair plumes on their reverse.

Most people chose hair work mourning designs from catalogs, then had them created by professional hair workers contracted by national mail order companies or private jewelers. Pointedly, their advertisements offered assurances that these one-of-a-kind creations would actually feature the locks supplied.

Other Designs and Details

Mourning jewelry, in addition to edgings of seed pearls “tears” and black bands (signifying grief), sometimes incorporated engraved words of comfort like “In Memoriam,” “Forever Loved,” or “Momma and Poppa.” “Yet those personalized with initials or names of the deceased,” explains Madeline Celletti owner at Bohemian Boutique based in Georgetown MA, “are far more desirable.”

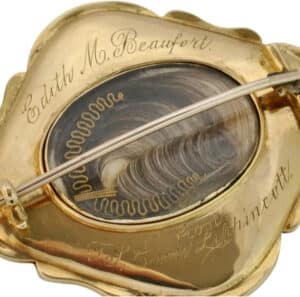

Yet those illuminating known loves and lives, like the agate, gold, and enamel glassed beauty inscribed “Edith M. Beaufort from J. S. Cann Lippincott,” are prized by collectors, genealogists, and historians alike. Research has revealed that Beaufort studied the occult with The Order of the Golden Dawn, while J.S. belonged to Gloucestershire England’s historic Lippincott Baronetcy of Stoke Bishop!

Getting Creative

By the mid-1800s, interest in hair work mourning jewelry was also sweeping America. Indeed, notes Godey’s Magazine and Lady’s Book, the most popular women’s magazine of the day, “Hair is at once the most delicate and last of our materials and survives us like love, It is so light, so gentle, so escaping from the idea of death, that, with a lock of hair belonging to a child or friend we may almost look up to heaven and compare notes with angelic nature, may almost say, I have a piece of thee here.” Hair, like love, outlasts the grave.

In response to its popularity, Godey’s not only published material promoting hair work but also offered instructions, printed patterns, and starter kits for do-it-yourself mourning creations. In addition to locks from the deceased, crafters needed tweezers, sharp penknives, delicate scissors, pencils, long pins, background palettes, thread, and ‘gum dragon’ adhesive. Frames and lockets were available commercially.

During the Civil War, as Yanks and Rebs set out for battle, many left bits of hair behind with loved ones. Should they lose their lives, they reasoned, these poignant mementos of shared affection could be incorporated into brooches, rings, or lockets worn close to the heart. After all, what was more moving than a part of oneself?

Victorian gold pinchbeck (brass/copper/zinc) glassed, pictorial swivel mourning locket/brooch with woven hair panel on the reverse. photo: www.rubylane.com

In later years, photography became increasingly accessible, and mourning jewelry often featured swaths of hair backed by images of the deceased. In time, these pieces fell from fashion entirely.

Those interested in exploring this historic art may find Campbell’s Self-Instructor in the Art of Hair Work (1867)—the most comprehensive work to this day—fascinating. Copies can be found online on GoogleBooks, Project Gutenberg, and at various bookstore sites.

Mourning jewelry not only remains little known among collectors but is considered morbid by many. So, few collect it. Though prices typically reflect their time period, material, size, condition, rarity, and historical significance, most pieces are generally quite affordable.

Related posts: