By Diane Dolphin

(Unless otherwise noted, all photographs are by the author, Diane Dolphin. All items shown are currently or formerly in the collection of the author.)

When people think of craftsmanship created by members of the Shaker religious communities, what might first come to mind are their exquisite furniture, crafted to merge refined form with functionality; or their elegant oval boxes, with their fine, delicate fingers. But many Shaker and sewing collectors focus on one of the Shakers’ most prolific industries: “fancy goods,” which includes many sewing items. The New York and New England Shaker communities produced a wide array of delightful and functional sewing goods for sale in their village shops and at local tourist destinations, including woven poplar boxes and pincushions, fingered oval sewing carriers, spool stands, and sewing clamps. Because these items were produced in large quantities for sale to the public—and because they were so charming and well-crafted—many of these items survive today, to the delight of collectors.

The Fancy Goods Industry

The Shakers have always produced goods for sale to businesses and the public to support their communities, such as cooperware, household goods, seeds and herbs, and food products. The sale of fancy goods became a major industry following the Civil War and spanned more than a century. In The Human & The Eternal: Shaker Art in Its Many Forms, Brother Arnold Hadd of the Sabbathday Lake Shakers describes the evolution of this industry. With industrialization and the rise of the middle class in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, leisure and tourism industries expanded. People began to travel to resort areas throughout the Northeast. The Shakers saw this as an opportunity to create small novelty items for sale to these tourists. Additionally, as the number of Shaker Brothers declined along with Shaker membership, the Sisters became the primary income producers, and fancy goods utilized their existing skills of sewing, weaving, and handiwork.

Many of these tourist items were made to appeal to a more Victorian aesthetic, thus earning the Victorian “fancy goods” moniker. Several Shaker communities published catalogs, such as the 1908 “Catalog of Fancy Goods,” produced by the Alfred, Maine community. In addition to sewing-related pieces, various communities produced countless other items, among them baskets, boxes, textile crafts, souvenirs, household items, brushes, dolls dressed in handmade Shaker outfits, and bonnets, to name just a few. The Brothers provided any “heavy work” needed, such as woodworking, and they helped with sales.

The Shakers sold these items in their own village gift shops, and they also went on the road, setting up sales displays at hotels and resorts. The Sabbathday Day Lake Shakers, for example, sold much of their fancy goods at the Poland Springs resort and at Maine seaside towns.

Shaker Fancy Goods: Poplarware Sewing Boxes and Accessories

Many of the sewing items produced by the Shakers are poplarware pieces. Poplarware describes the large variety of small boxes and items that were created using finely woven poplar wood. The craft was invented by and unique to the Shakers and was a major industry for several communities.

Interior is sectioned and lined in green velvet.

The Mount Lebanon Shakers first created woven poplar cloth in the 1860s, and the poplarware industry continued well into the 1900s in several communities. Poplarware was primarily produced at Mount Lebanon in New York, Sabbathday Lake and Alfred in Maine, and Canterbury in New Hampshire. The Enfield, New Hampshire, and Hancock, Massachusetts communities also produced poplarware, but in limited volume. The Sisters would produce thousands of poplarware items during the winter months for sale in the coming tourist season.

To make poplarware, poplar wood was shaved into paper-thin, narrow strips of only 1/16th of an inch wide. These strips were woven with thread into sheets, which were then applied to a paper backing for stability. Several communities created their own unique weaving patterns, and some makers incorporated dyed poplar, ash, or sweetgrass for a striping effect. The resulting “poplar cloth” was then applied to paper board or wood, and constructed into poplarware items.

Poplar boxes featured woven poplar exteriors, finished with white kid leather edging and ribbons, and were usually lined with colorful silk satin, although occasionally with velvet or other material. They were produced in a wide array of shapes, sizes, and intended uses, from small, square “handkerchief” boxes, to half-moon-shaped jewelry cases, to diamond-shaped “card trays.” Sewing boxes came in many shapes, from octagonal, square, and clam-shell shaped, to elaborate sewing “work boxes,” also called “caskets,” which resembled fancy handled baskets and were decorated with sewing accessories on the lids. The sewing boxes were fitted with small accessories such as pincushions, needlebooks, molded wax thread waxers, and strawberry-shaped emeries.

Poplarware pincushions were also produced. They consisted of a woven poplar “basket” base, fitted with a velvet tomato-shaped pincushion. Most poplar pincushions are round, but other shapes were produced, including square and clamshell-shaped. Small poplar needlebooks had woven poplar covers and contained woolen “pages” inside to hold needles.

As the availability and ability to produce poplar cloth declined by the mid-1900s, the two remaining communities, Sabbathday Lake and Canterbury, continued to produce similar sewing items but replaced the poplar cloth with other fabrics, such as upholstery fabric and leatherette.

Shaker Fancy Goods: Sewing Carriers

An extremely popular sewing-related item was oval sewing carriers: wooden carriers resembling traditional Shaker oval boxes with fine, elongated fingers, but with added swing handles. The Sisters lined these with colored cloth—usually satin or brocade—and outfitted them with matching pincushions, needlebooks, emeries, and waxers.

Sabbathday Lake was the primary producer of sewing carriers. Brother Delmer Wilson began producing sewing carriers in the late 1890s, and his carrier industry soared within 10 years to more than 1,000 a year. The boxes were made of applewood, cherry, maple, and quartersawn oak. The sewing carriers were unlidded, showing off their pretty outfitted interiors. Many boxes are marked with the Sabbathday Lake trademark, which includes their community name and the monogram, “SC,” for “Shaker Community.” The Alfred community in Maine also produced their own sewing carriers, which were very similar; however, many of them featured fingers that pointed to the left, whereas most Shaker carriers have fingers pointing to the right.

Sister Lillian Barlow and Elder William Perkins in Mount Lebanon, New York produced their own unique sewing carriers from the 1920s to 1940s. They were made of gumwood, stained a medium to dark brown, and varnished, leaving the tiny copper tacks shiny. They had lids and were lined in patterned brocade silk; some had sewing accessories, while others did not. Just a few of them are marked with a Mount Lebanon label.

Shaker Fancy Goods: Spool Stands and Sewing Clamps

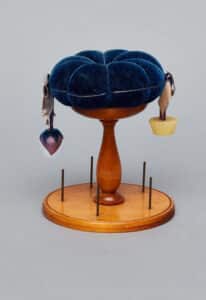

Other appealing and popular items were “spool stands,” also known as sewing stands or spool holders. The round wooden base of these stands had metal pins that could hold different spools of thread, keeping them all at the sewer’s easy disposal. In the center of the base, a finely turned wooden pedestal ends in a round wooden disk that holds a large round tomato-shaped pincushion. Sewing accessories were often attached to the pincushion with silk ribbons. However, the silk often grows fragile with age and breaks, so it’s a challenge today to find spool stands with the original accessories still attached.

Besides the spool stands, some communities, including Hancock, Massachusetts, and Canterbury, New Hampshire, produced sewing clamps to hold down the cloth being worked on and have a pincushion handy. They were made of turned wood (usually maple), and had round pincushions on top that were plainer than the tomato-shaped ones on the spool stands. Depending on the style, clamps could be screwed down to the edge of the sewer’s table by tightening a wooden key or by rotating a round wooden disk on the clamp’s threaded shaft.

Shaker Fancy Goods: Sewing Accessories

Many of the sewing accessories that fitted the sewing boxes, carriers, and stands were also sold separately. Round melon or tomato-shaped pincushions of satin and velvet came in different sizes and colors. Decorative threadwork segmented the pincushions into sections, and the thread was woven or knotted around the center, often looking like a tiny spider web. Similar pincushions produced in the mid-1900s were made from cotton prints with colorful patterns. Strawberry-shaped emeries, usually made of satin with velvet caps and filled with sand-like emery powder, were used to sharpen needles. Besides the strawberries, emeries were also created using walnut shells, seashells, and as little cloth daisies. Little thread waxer “wax balls” were produced in several shapes, including tarts, balls, and cylinders. Sewers would run their thread across the waxer to make it glide more easily through the cloth.

The Shaker Sisters produced many other sewing-related items besides those mentioned here. Their vast number and array of types and styles are a delight to today’s collectors. Even among similar items, it seems no two of these hand-made pieces are exactly alike, making every new discovery a useful and delightful addition to their collection.

Want to learn more about Shaker Fancy Goods? You can start by visiting the various Shaker village and museum websites, including Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village in Maine, the remaining active Shaker community, to gain a deeper understanding of the Shakers’ religious and communal life and work, as well as learn about their industries. Several sites have online collections of Shaker-made items you can browse or search. You can also plan a visit in person to enjoy tours and exhibits (check their websites for public hours, any current restrictions, and current exhibits and programs). In addition, the books below, which provided information for this article, describe the life, religion, and work of the Shakers and illustrate many of the products the Shakers made and sold to the public.

About the Author:

Diane Dolphin is the owner of D. Dolphin Antiques. She has been learning about and collecting Shaker ephemera and Shaker-made items for the past twenty years, after first becoming fascinated with their religion, philosophies, and community life while visiting several Shaker villages and reading their publications. Diane is also a retired college faculty member who taught writing, media, and organizational communications.

Sources:

From Shaker Lands and Shaker Hands, by M. Stephen Miller. Published in 2010 by University Press of New England.

Handled with Care: The Function of Form in Shaker Craft, by Christian Goodwillie and M. Stephen Miller. Published in 2006 by Hancock Shaker Village.

The Human & The Eternal: Shaker Art in Its Many Forms, published by the Sabbathday Lake Shaker Museum.

Shaker Baskets & Poplarware: A Field Guide, Vol. III by Gerrie Kennedy, Galen Beale, and Jim Johnson. Published by Berkshire House Publishers, 1992.

Ingenious & Useful: Shaker Sisters’ Communal Industries, 1860-1960, by Brother Theodore E. Johnson. Published by the United Society of Shakers, Sabbathday Lake, 1986.

The Shakers: From Mount Lebanon to the World, Michael K. Komanecky, Editor. Contributions by Leonard L. Brooks, Christopher Brownawell, Michael S. Graham, Jerry V. Grant, Brother Arnold Hadd, Michael K. Komanecky, Stephen J. Stein, David Stocks, and Angela Waldron.

Related posts: