By Donald-Brian Johnson

Ever watch Mad Men? If you were one of the many fans of that series, which meticulously recreated American life in the early 1960s, after awhile you started to notice something: nearly everyone on Mad Men smoked. A lot. It’s something you don’t see much anymore, in the movies, or on TV, unless in a true-to-the-times flashback. If someone’s smoking in a story set in the present-day, chances are good that the character is either a villain, an eccentric, or possessed of some unfortunate character flaw. And, as puffing performers are quick to point out in promo interviews, all that onscreen smoke is actually a smokescreen: herbals, or other non-tobacco, non-addictive alternatives have been used to create the necessary illusion.

Smoke Dreams

Smoking (as if you needed to be told) is no longer glamorous. But once upon a time, smoking on the silver and small screens served as a scene-setter and character-indicator. Think of sultry Marlene Dietrich, and other femmes fatale of the 1930s and ’40s. Swirls of smoke from omnipresent cigarettes added to their mysterious aura. And, when Paul Henreid lit two cigarettes in Now, Voyager, then passed one along to Bette Davis, you just knew their romance would soon be heating up. Wreaths of smoke festooned the TV tube as well. Rod Serling smoked. So did George Burns and Groucho Marx. Even those fresh-faced young vocalists on Your Hit Parade (“brought to you by Lucky Strike”) lit up with cheery regularity.

Tobacco Road

The first ashtrays really weren’t much to look at. In fact, when introduced around 1850, they were referred to as “ash-pans,” cup-like containers without cigarette rests. The “ash-tray,” much the same as we know it now, debuted in the 1880s, and made its first dictionary appearance in 1887, defined as “a dish for tobacco ashes.”

Overly-fussy Victorian ashtrays, and sinuously-sculpted Art Nouveau ones, will always have their fans. Most ashtray collecting today, however, focuses on those produced from the Art Déco through the Mid-Century Modern eras – roughly, from the late 1920s through the 1960s. Smoking was then at its most socially acceptable, cigarette advertising was at its peak, and ashtray production was big business.

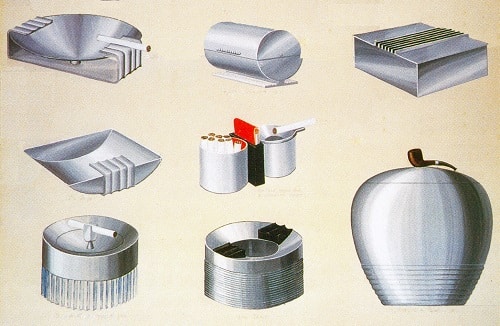

Sometimes, it seemed that the only people who didn’t smoke during the 1930s were those in diapers. Although it was the Depression, consumers still craved at-home elegance, but at bargain-basement prices. They also craved tobacco. Answering the call for inexpensively elegant housewares, ashtrays included, were companies like the Chase Brass & Copper Co. Chase and its contemporaries crafted the look of luxury from such relatively affordable metals as copper, brass and nickel. Its most successful products, however, mimicked the sleek sheen of silver, but with a much less costly and more “modern” chromium finish. Buyers quickly responded, opening their pocketbooks for a multitude of attractive, moderately-priced Chase specialty items. Among them: buffet dishes, decorative accessories, barware and all those ashtrays.

At one point during the ’30s, Chase offered over 100 different “Smoker’s Articles,” rivaling its listings for dining accouterments. The Chase catalog burbled that its offerings for smokers were “as finely done as expensive jewelry. Our new smoking articles are fresh and beautifully finished to the last detail, some heavy and important-looking in black and brass, some with many-colored etched covers.”

As there are only so many things an ashtray can do (well, only one thing, actually), the inventive emphasis was on performing that duty more attractively and efficiently.

Among the Chase brainstorms: the “Riviera,” complete with an operable numbered roulette wheel; the “Snuffer,” with a golden fish serving as a cigarette extinguisher, and the “Pelican,” shaped just as one might imagine. A tilt of the Pelican’s bill, and ashes disappeared inside its tummy (presumably to be dumped out later, before indigestion set in).

Somewhat racier were the metal figural ashtrays created for Frankart by Arthur von Frankenberg. An androgynous nude sylph adorns most Frankart smoking accessories, perkily perched on, or patiently holding, the ashtray itself. Since von Frankenberg sculpted from life (complete with props), his longtime model/muse Leone Osborne was evidently tireless.

Whether figural or functional or both, Art Deco metal smoking accessories seem to have danced directly off the screen, where they’ve perhaps been gussying up the set of a glamour-filled Fred Astaire/Ginger Rogers movie. And that, of course, was the idea.

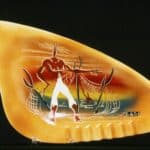

For those in search of a more down-to-earth smoking experience, companies like Syroco (Syracuse Ornamental Company) were happy to oblige throughout the late 1930s and ’40s. Although possessing the look of carved wood, Syroco novelties (which included everything from tie racks and thermometers, to plaques and paperweights) were actually

made of a wood composite. The compressed mixture of wood flour, waxes, and resins used to create “Syrocowood” meant that non-charring “wood” ashtrays were now a possibility. Many, however, came with their own glass insert dishes for ease in cleaning and to preserve their cosmetic appeal. While cavorting carved bears and cascading bowling pins made for clever Syroco ashtray themes, most in demand today are those created for special events, such as the 1939 New York World’s Fair.

Smoke Gets In Your Eyes

Ceramic ashtrays captivated consumers post-World War II, and continued to hold them in thrall throughout the 1960s. Think of a popular ceramist of the period, and chances are good that at least one ashtray made its way into his or her portfolio. Hedi Schoop came up with a quaint bug-eyed bird. Georges Briard experimented with porcelain. Both Roselane and Gonder took brief detours into ashtray production. Harris Strong stepped away from his tile work long enough to create slab-like ashtrays decorated with primitive stick figures. And, Sascha Brastoff and Marc Bellaire churned out ceramic ashtrays by the truckload.

Brastoff’s smoking accessories were populated by his wispily dreamlike “Star Steeds,” “Jeweled Peacocks,” and “Persians.” Bellaire’s eerily muscled, eyeless “Beachcombers” and elongated, masked Mardi Gras revelers were a less comforting, if more arresting, presence. Each found favor, however – and each fulfilled its dual mid-century purpose: ashtrays thoroughly useful, and at the same time, thoroughly, decoratively, modern.

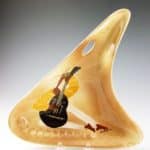

Most ubiquitous in the lineup of mid-century smoking paraphernalia, however, are glass ashtrays (perhaps because they are inexpensive, and the easiest to clean). Even today, glass ashtrays continue to endure, lurking furtively in those increasingly-rare “smoking-permitted” areas. There are the clear, impressed-pattern or colored glass ashtrays of the Depression years. There are logo ashtrays, advertising long-vanished restaurants, bars, and service stations. And, at the top of the heap, there are ashtrays by Higgins Glass.

Specialists in fused glass (where an interior design was captured between one or more glass layers) Frances and Michael Higgins soared to national prominence through glassware produced for Dearborn Glass Company from 1957 to 1964. The Higgins specialized in “useful” decorative housewares. At Dearborn, the definition of “useful” seemed to correspond with “the sky’s the limit.” The company’s line of “Higginsware” included nearly every possible variation on a homemaker’s dream, from entire tables set with Higgins dishes, to Higgins candleholders, vases, clocks, lamps, and elaborate, multi-tiered serving dishes.

Of course, some Higgins ideas proved more interesting in theory than in reality. “Gemspread,” a lovely irregular geometric-shaped ashtray, featured a border studded with glass chips. Said Frances Higgins, “that was one of our handsomest patterns, but it didn’t sell very well. Too hard to clean. The ashes got stuck in the chip.” Another disappointment: “Little Girl,” featuring an interior design of a perky flowered-hat-wearing youngster. Asked why it didn’t sell well, Mrs. Higgins responded, “Well, just think about it. Would you want to put out a cigarette in that sweet little girl’s face?”

Although Higgins Glass continues to thrive today, ashtrays, no matter how eye-catching, are no longer on the Studio’s docket. Times change. As Frances Higgins once noted, “we don’t make ashtrays anymore. You just can’t sell them.”

Down To My Last Cigarette

Fortunately, you can collect them. Vintage ashtrays, if no longer needed for their original

use, can be imaginatively repurposed. Among the myriad of possible new callings: coasters; jewelry/trinket trays; change trays; flowerpot trays; business card/mail trays; key holders; TV-remote holders; eyeglass stands; fruit plates; popcorn/chip bowls; cheese trays – even soap dishes!

Chase reference materials courtesy of Barbara Ward Endter

Photo Associate: Hank Kuhlmann

Donald-Brian Johnson is the co-author of numerous books on design and collectibles, including Postwar Pop, a collection of his columns. Please address inquiries to:

donaldbrian@msn.com.

Related posts: