The American Arts & Crafts Movement and its Women Practitioners

By Catherine W. Zipf

In 1903, Waldo Waterman died unexpectedly. Once his debts were paid, his wife, Hazel, was left with a very small income, a modest insurance policy, and three children. And at age thirty-eight, Hazel had no training in any profession open to women – secretary, teacher, or nurse. What was she doing to do?

In desperation, she turned to her San Diego friends, Alice Lee, Katherine Teats, and architect Irving Gill. Gill taught her architectural drawing at his studio and paid her to render designs, which she did on a drafting table at home. Lee and Teats commissioned three houses from her while she was still in training. Two years later, now a seasoned practitioner of the Arts & Crafts, Hazel Waterman began her first project as a professional architect. For the next decade, she designed buildings at home while raising her three children.

Waterman was one of many women who found opportunities for work within the American Arts & Crafts Movement. Unlike other women of the time, Arts & Crafts women were able to build professional careers for themselves in a multitude of ways. Cloaking their work in the socially acceptable guise of artistic production, these women founded businesses, invented technology, and built economic markets, all at a time when women had few professional options. The key to their success lay in the tenets of the Arts &

Crafts Movement and its connection between good design and the home.

The development of the American Arts & Crafts Movement marked the end of a century that had redefined women’s relationship to work. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, social norms dictated that women direct their labor towards the home and children. By mid-century, however, women’s roles had shifted toward the cult-of-domesticity values of piety, purity, and submissiveness. According to these values, women were strongly associated with domesticity and morality. They were not supposed to work outside the home.

Arts & Crafts women benefited most from the movement’s ideology. As defined by its English founders, John Ruskin and William Morris, Arts & Crafts ideology emphasized the individuality of the craftsman and the personal exploration of art. The craftsman was given the freedom to select whatever design motifs, forms, and techniques s/he deemed appropriate. Education was key, as was the movement’s club-based format, which made tools and communities accessible to women. As a result, the Arts & Crafts Movement from its very beginning embraced a wide and very diverse variety of objects and people.

The appearance of English Arts and Crafts objects in the exhibits of the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia sparked a revolution in American taste. American artists seeking to imitate the English Arts and Crafts style formed an early grassroots movement of schools, clubs, and other organizations. Women were fundamental to this grassroots movement. For example, Mary Louise McLaughlin, one of the earliest women working in America, formed the Cincinnati Pottery Club in early 1877, shortly after the Centennial Exposition. Run entirely by women officers, it was the first women’s ceramic club in the country and one of the first to hold annual receptions at which members could sell their work. The Cincinnati Pottery Club disbanded in 1890, but many members went on to considerable personal and professional success.

Despite their importance, these early women were often overshadowed by men. In 1879, Candace Wheeler joined Louis Comfort Tiffany, Lockwood DeForest, and Samuel Coleman in founding Associated Artists, a New York-based interior design firm. Wheeler’s responsibilities centered on creating textiles for the firm’s clients, including handmade curtains, tapestries, and embroideries. For commissions like the George Kemp House (1879) and the Seventh Regiment Armory (1880), this work was considerable. Yet, the firm’s advertising listed her only as “Associated Artist.” Choosing to own this moniker, when Associated Artists disbanded in 1883, Wheeler took the name as part of her settlement and used it to found a new firm.

In fact, aside from a tour by Oscar Wilde in 1882-83, Arts & Crafts men did not catch up to the movement’s women until the 1890s. Frank Lloyd Wright entered private practice in 1893, Grueby Pottery was founded in 1895, Elbert Hubbard founded Roycroft in 1895, and the Gustav Stickley Company was founded in 1898. Although the perception of Arts & Crafts history is to the contrary, women designers guided this grassroots Arts & Crafts Movement for nearly two decades before the movement’s major male figures arrived.

This early generation of women designers believed that art could proactively generate change. By the mid-1880s, their efforts had caused a massive expansion in Arts & Crafts production. As the grassroots movement evolved into an organized network of individuals and groups, McLaughlin and Wheeler were joined by more and more mid-level workers who fabricated handmade products, designed and oversaw production methods, and managed daily operations. For women, these supporting positions offered two attractive benefits: they were socially acceptable, and they contained the potential for career growth.

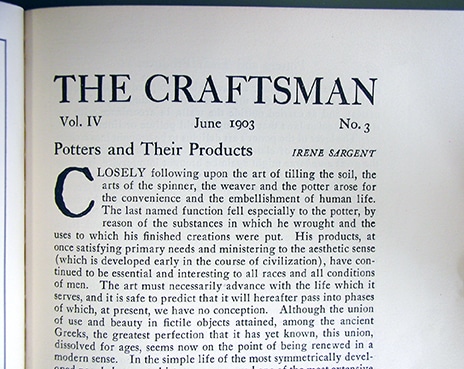

The acceptability of Arts & Crafts jobs was extremely important and derived from the Movement’s focus on the home. Arts & Crafts artists focused on creating objects, furniture, wallpaper, curtains, embroidery, tapestries, vases, and tiles intended for domestic use. Many American Arts & Crafts designers worked at home or in a home studio. And, Arts & Crafts magazines worked hard to reinforce connections between the movement and the home by printing articles on how to use Arts & Crafts objects. For example, in October 1903, “The Craftsman” published an article explaining how dining room furniture “may be arranged, at a slight expense, in any ordinary private or apartment home.” One important advantage, the article pointed out, “gained by this simplicity and spareness [is] the comfort of the guests …” At stake was more than just connecting art and home, but actually living with the art at home. Incidentally, the article, “A Simple Dining Room,” was written by the magazine’s editor, a woman named Irene Sargent.

The movement’s emphasis on social reform also helped make Arts & Crafts jobs acceptable for women. Although many designers, like Stickley, did not hide their economic agenda, a sense of social reform pervaded the Movement. Ruskin and Morris wrote frequently about their commitment to reform through art. In America, similar trends were evident. Candace Wheeler founded several networks designed to change society by making women’s work more valuable. Sargent, in the article quoted earlier, argued that the dining room “would seem to be a step toward the substitution of luxury of taste for the luxury of cost; an end toward which every American architect, decorator, and owner of a home should work, as an effort against the materialism which threatens our rapidly developing and prosperous country.” Social reform lay well within the domain of women, extending naturally from their position as moral guardians and homemakers.

Further advantages lay in the Movement’s promotion of handmade goods. Industrialization had caused a significant decline in the value of art forms like embroidery, weaving, and pottery, which were typically done by women. Arts & Crafts ideology fostered a new appreciation for handmade objects by declaring them superior to industrial products. Art potters, in particular, worked especially hard at changing attitudes. McLaughlin, Storer, and others promoted the handcrafted aesthetic of their pottery as a positive attribute and stressed it as a feature that conveyed the honesty of the worker. Efforts to change this perception were accompanied by a strong sense of professionalism. Arts & Crafts objects were better because they were handmade. They were also better because they were created by experts and were not the result of “amateur doodling.”

Women were first to organize Arts & Crafts societies. They were first to create Arts & Crafts objects. They worked at or for nearly every major Arts & Crafts business, organization, or community. They created techniques for improving handcrafted technology. They designed buildings and objects in nearly every medium. They wrote books and articles that defined the movement’s ideals, values, and style. They encouraged others to join and made it easy for them to do so. Women were not just involved in the movement, they were the movement.

Catherine W. Zipf, PhD, is an award winning architectural historian and author with expertise in historic preservation. Her research focuses on women’s participation in architectural and decorative arts history. She holds an AB from Harvard University and a MaH and PhD from the University of Virginia.

Zipf writes frequently for a wide range of print and online publications. She is a contributing author to the anthologies “Monuments to the Lost Cause” and “A Gendered Profession,” and has written scholarly articles for “Buildings and Landscapes,” “Radical Teacher,” and “The Journal of City, Culture and Architecture.” She also writes a monthly column on architecture for “The Providence Journal.” Zipf’s research has been supported by organizations like The National Trust for Historic Preservation, The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and The Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation. She is currently writing her second book, “Making a Home of Her Own: Newport’s Architectural Patronesses, 1850-1940.”

Related posts: