Makes Good Cents: Vintage Gumball Machines

by Douglas R. Kelly

All of the debate surrounding the U.S. government’s potential elimination of the penny—a coin with a long and illustrious history—ignores what I think might be the biggest negative impact of all: if this goes through, what will we put in vintage gumball machines that we run across at flea markets, in antique shops, or at the dry cleaners up the street that has that vintage Oak machine on the metal stand?

There isn’t much that a penny will buy these days. But there was a time when the little copper disc was a passport to fun, at least for a few seconds, when you put it in the slot of a gumball machine and turned the handle. Machines that were made from the 1930s into the 1960s aren’t hard to find, for the most part, and unless you chance upon a real rarity, many of them still are very affordable. Over the last 25 years, with the way the Internet opened up new avenues for finding vintage stuff, the market for these machines (those that generally are in the $200 to $800 range) has cooled. That translates into buying opportunities for those who arm themselves with some knowledge about these devices that often were referred to as “silent salesmen.”

About the Globe

For this annual glass-focused issue of the Journal, it seems to me that we should look first at the most vulnerable part of vintage gum machines, which are their glass globes. For obvious reasons, these globes could be damaged more often and more seriously than the cast metal and aluminum components of the machines. Most units were designed and manufactured to withstand daily interaction with the general public, but even the strongest machines had their limits. Some manufacturers started using plastic for their globes during the 1950s, but most machines continued to use glass.

Replacement globes now are available for most of these machines, and some of the repros are made from the original tooling that was used in 1934 or 1958. Still, there are clues to look for with a glass globe. “New globes tend to have unfin-ished edges at the openings, [while] original ones are polished,” says Tom Tolworthy, a coin-op and gambling machine expert with Pennsylvania-based Morphy Auctions. “And newer globes are thinner – noticeably so.”

The thinner glass that globes are made with today makes some sense, given that these machines no longer have to take a beating in retail settings and, therefore, don’t require heavy glass. But Tolworthy shared with me a couple of things about globes that I wasn’t aware of, things that shed some light on this corner of the coin-op machine world. He said that most machines made after about 1920 were “route machines,” meaning machines that were owned and maintained by individuals who shared the profits with shopkeepers. “That means there were a lot of [this type of machine], and that’s what drove the market to produce [repro] globes. Most vending machines prior to 1920 were single purchases by shopkeepers, who owned that machine, so there were a lot less of those.”

I’d seen early gumball machines from that period with globes that had marks and imperfections, and Tolworthy said the globes on those units likely were non-route machines. “A non-route machine, if it needed a globe, generally had it made by a glass blower. These globes are not smooth, [and] in [the] reflection, you can see ripples.”

Decal Details

The globe of a gumball machine, of course, sported the decal that told the buyer what they were getting and for how much. Some decals were adhered to the inside of the globe, others to the outside, and finding a machine with the original decal is the goal for most collectors. If the decal is only partly there or missing altogether, there are repro decals made for many machines, and some are very sharp and well-done.

However, as in many categories of antiques, originality generally is king. A perfect, unrestored machine with the original globe, original decal, and original paint (or porcelain in some cases), will command a much higher price than a machine that’s been restored or repaired, or even merely touched up.

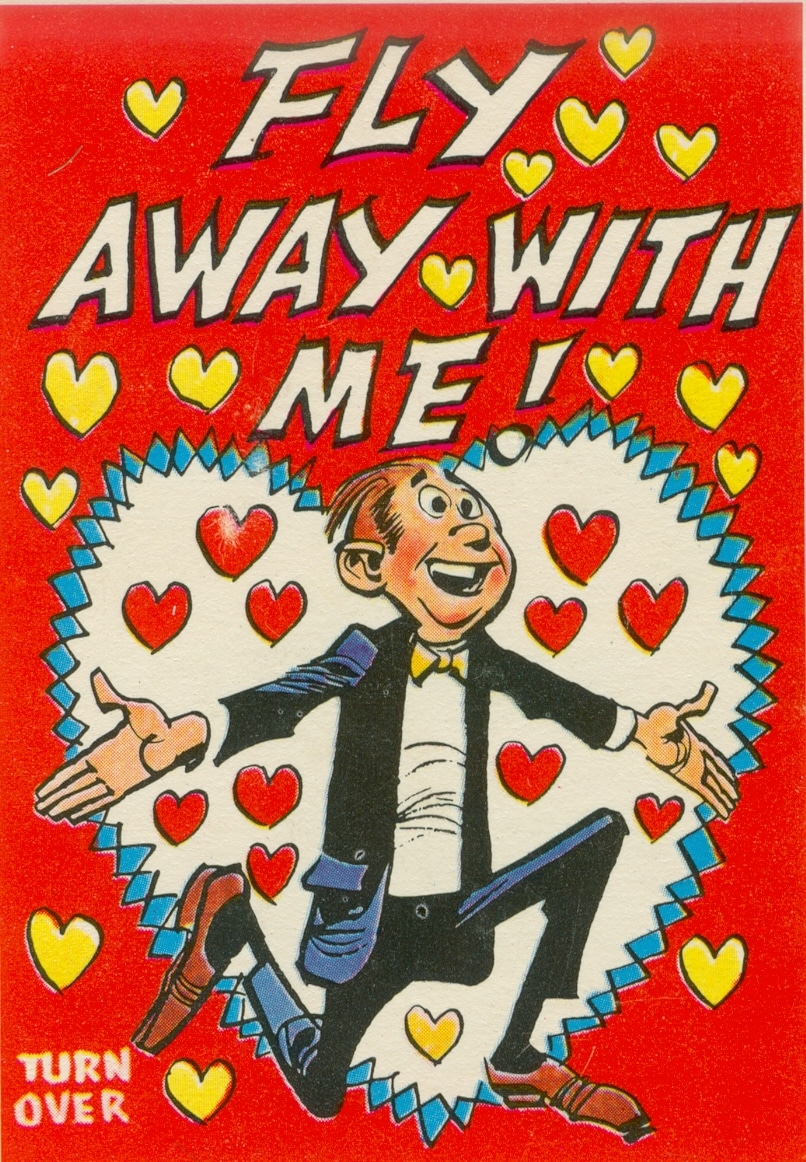

Some manufacturers, beginning probably after World War Two, used cardboard labels (small signs, really) that were adhered to the inside of the globes. Like decals, these labels often are miniature works of art in themselves, offering a little glimpse at life in 1950s or 1960s America.

It would be reasonable to assume, because these machines stored and dispensed a food product, that corrosion might be a factor today. But that’s generally not the case. The majority of these machines were made of aluminum (with some early machines being cast iron), and generally, they can be washed out and they’ll look and function just fine. The exception is with nut machines because the product contained salt, and that often corroded interior components.

The Works

Some buyers don’t care whether a gumball machine works the way it was originally intended to work. They’re more interested in it for the decorative or aesthetic value that it offers. The design of many of these machines was both beautiful and functional, and it was often the look of the machine, as much as the product being offered, that separated customers from their cash.

But if you want a machine that gives you that spearmint or cherry or licorice-flavored ball when you put your coin in the slot, you’ll want to know about its functionality early on. If the seller has the key to the machine, that’s a good start, although you may be reluctant to disassemble a 1947 Victor Model V in the middle of a crowded show or a busy store.

That’s when your penny (or nickel or dime) comes in handy. As long as the seller is cool with it, put in the coin and turn the knob. If there are no gumballs inside the machine, you should be able to see at least a part of the mechanism working as you turn the knob. There should be some resistance as wheels and springs do their thing, but the action should feel smooth. If the machine does have product inside it, you’ll know pretty quickly whether or not it works.

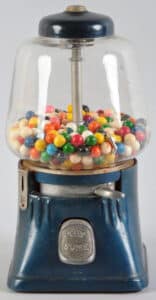

A 1950s example like this will generally sell for $300 to $400.

By the way, the absence of the key doesn’t have to be a deal-breaker. A locksmith can make a new key for many older machines. The cost for this can be $25 to $50, so this should be a part of the purchase decision. Additionally, some gumball machines were designed to attach to a metal floor stand rather than to sit on a countertop. Finding a machine complete with its original stand usually means a higher price tag.

The Market

Machines made before 1920 are generally considered rare, no matter what condition they turn up in. But for 1940s to 1960s machines, it’s not difficult to find examples that are in excellent original condition. (Finding gumballs that are the correct size for that 1933 Northwestern? That can be more challenging, although there are gum and candy makers today that produce products that will fit in many vintage machines.) In fact, it’s surprising how often gumball machines turn up in their original shipping boxes, unused for all these years and just waiting to be filled with those little round chewy treats.

“Vending machines in the $200 to $800 price range have remained virtually constant for the last 20 years,” says Tom Tolworthy. “The reason for this is that, as collectors advance and add machines to the top value of their collection, many

make room by selling from the bottom value of their collection, so these machines are not in demand. Most collectors have an example or two and, because these machines tended to be route machines, there are a lot of them.”

Learn More

Even with all of the information available on the Internet, many people looking for the skinny on gumball machines still turn to a book: Silent Salesmen Too, written by Bill Enes and published in 1995. It’s the bible of the hobby, and along with gum, nut, and candy machines, it covers match, pen, and even perfume dispensers. The author also included more than 20 pages of original advertisements, which offer a peek into the cultural context in which these machines were used. It’s not cheap—copies often sell for $50 or more—but it’s loaded with good information and photos.

And as with other categories of antiques, there’s an association for all of this, and it’s the Coin Operated Collectors Association, or COCA, which holds meetings and offers members a host of resources on its website. They also publish a three-times-a-year magazine, COCA Times, which covers everything from slot machines to arcade games to gumball machines. Check it out at www.coinopclub.org

Douglas R. Kelly is the editor of Marine Technology magazine. His byline has appeared in Antiques Roadshow Insider; Back Issue; Diecast Collector; RetroFan; and Buildings magazines.