By Kristen Berggren, Program Coordinator

The New England Carousel Museum has been an important fixture in the city of Bristol, CT since it was founded in 1990. At that time the museum was a tenant in the converted hosiery factory on Riverside Avenue and had only one horse to its name. The menagerie of wooden animals has grown substantially over the past thirty years—today, over one hundred antique carousel figures are on display at any given time—some figures are in our permanent collection while others are on long term loan to us from private individuals, and the factory building is now owned by the Museum.

Let’s Look at the History

The numerous horses, giraffes, deer, pigs, and more come off of long-dispersed carousels from all over North America and Europe, and there is a history behind the creation of each one. Carousels as we know them started in 17th-century Europe as crude human or animal-powered training devices for horsemen to practice their skills for battle as well as tournaments. With the advent of more advanced weaponry, these training devices became obsolete and were instead used by the nobility for entertainment. Although they were conceived abroad, carousels would eventually reach their pinnacle of artistic excellence here in America.

In the 1860s with the Industrial Revolution carousel production began in a factory setting. The introduction of the steam engine and later electricity ensured that carousels could turn faster while their diameters increased, along with the number of horses and exotic “menagerie” such as lions, giraffes, and camels populating each platform. By the 1880s street trolley companies, seeking increased ridership on the weekends would place parks or picnic groves with carousels at the end of their lines for the growing middle class to enjoy.

Craftsmen on the Move

Also around this time, an influx of skilled European woodworkers began arriving in this country; men who were trained as cabinetmakers and sculptors for churches and synagogues in their home countries of Germany, Italy, Russia, and elsewhere often found employment in the burgeoning carousel factories. Several centers of carousel industry developed, including the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia, and Coney Island in Brooklyn. Here in this new country, these recently arrived immigrants found the freedom with which to let their creative geniuses soar, and by the 1890s horses were leaving their workshops the likes of which had never been seen in Europe or anywhere else; accurately-proportioned animals frozen in time at the apex of their leap, with flaring nostrils, intricate manes, expressive faces, and trappings aplenty sometimes fanciful and shiny, sometimes realistic and historically accurate but always eye-catching.

built in 1925 by the Philadelphia Toboggan Company.

Americans quickly developed a love affair with these majestic creatures, however during the Golden Age of the wooden carousel industry from 1880-1930 they were not considered art but commercial commodities; it was believed that the larger and fancier the horses and carousel mechanism, the more income they would generate. For a time this seemed to be true; carousel production and operation in the early 1900s were lucrative businesses. At this time there were approximately twenty carousels at Coney Island alone, the largest and most successful of which could bring in $500 in nickels on a busy day (about $15,000 today) as thousands of eager patrons would hop on the platform, hoping to grab the brass ring and win a free ride.

Unfortunately, the duration of this love affair was limited. Rising labor costs, the Great Depression, and changes in technology all contributed to the demise of the wooden carousel. Factories had to switch to automated carving and eventually cast figures out of aluminum in order to stay in business. High unemployment in the 1930s meant that many families had less disposable income to spend. Countless wooden carousels fell into disrepair and simply disappeared as maintaining them became too expensive and time-consuming. The handful of individual wooden figures rescued from defunct platforms were considered decorative items at best and junk at worst.

A Comeback for Art’s Sake

This outlook changed around 1973 with the establishment of The National Carousel Association, which helps fund the preservation and raise the awareness of existing antique carousels. Many publications on carousel art followed, and the American love affair with carousels has now come full circle as wooden carousels are being built and figures carved once again, and the public continues to appreciate the wooden carousel as not only a form of entertainment but as a work of art.

The New England Carousel Museum shares in this dedication to the preservation of antique carousels, of which there are fewer than 200 around today. Tradition is alive and well here, as we carve new carousel pieces and restore antique ones for both private collectors and carousel operators using early 20th century techniques. Master Painter Judy Baker explains our painting process: “We use Japan Oils which are the same types of paint that would have been used at the beginning of the last century, except the lead has been removed. We have a basic palette of colors and we mix variations of the different shades.” The paint is applied entirely by hand, and dozens of brushes of different sizes, shapes, and textures are used at a time for painting, blending, and pinstriping. “As the horse is being painted you can see it come to life in front of your eyes and it’s very exciting, and you never want to take away from the carving detail. You want to enhance it.” Our current restoration projects are always on display for visitors to view.

A Collection of Different Styles

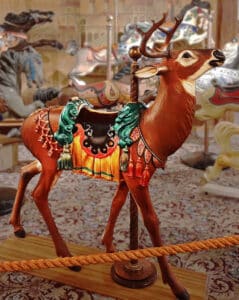

simply decorated, as they had to be easy to transport. However, some larger and more ornate figures were produced by the same

factories on occasion, like this deer with

real antlers, carved on special order at the Allan Herschell factory of North Tonawanda, NY in 1922.

Pictured at center is a c.1905 giraffe from the factory of Gustav Dentzel. This fellow, with his head up in an unusual “leaf eater” pose, has been partially stripped of old varnish and shows old factory paint beneath.

When you visit the Museum you will notice that the figures are grouped by carving style. There were three styles of carousel carving that developed in America during the Golden Age: the Philadelphia style, the Coney Island style, and the Country Fair style. Philadelphia figures are renowned for their literal and sculptural qualities and realistic proportions; they look very much like real horses and often have beautiful secondary carvings on the saddleback (called the cantle) or on the chest. We like to joke that these horses are so life-like that if you held out an apple to one of them they would actually eat it!

The Coney Island figures are products of the location where they originated. As a neighborhood full of carousels, coasters, and countless other amusements, Coney Island was an exciting place to visit in the early 20th century, and the horses on the carousels there reflected this energy well. The Coney Island carvers were renowned for creating flamboyant, animated, emotional figures with wide-open mouths, elaborate manes, and plenty of jewels to reflect the newly invented electric lights that dotted the carousel scenery panels. The trappings and manes of these horses are often enhanced with the addition of real 23-karat gold leaf, which is thinner than paper and takes a great deal of patience to apply.

Designed to be transported frequently on portable carousels while sustaining little damage, Country Fair style horses show the simplest and most common style of American carousel carving; they tend to be smaller and less realistic than those from Philadelphia and Coney Island. The “battle horses” of the carousel world, they took a lot of abuse, so great care had to be taken with the carving; the ears were usually carved into the mane so they wouldn’t break off, and the legs had to be designed in such a way that allowed the horses to be stacked easily in the back of a wagon or a railroad car as they made their way from one fair to the next. Although many antique portable carousels are still in operation today, virtually all of them have retired from traveling and operate in one fixed location to help preserve them and minimize repairs; the figures on portable carousels at today’s carnivals are almost always made of either aluminum or fiberglass, but are often molded or styled after the figures of yesteryear.

If your travels take you to New England this fall, give the New England Carousel Museum a visit. They are located at 95 Riverside Ave (Rte. 72) in Bristol, CT. The Museum is open on Saturdays from 10-5, and Sundays from 12-5 with guided tours at 12 and 2, or by appointment during the week. Also on-site and included with admission are an operating modern fiberglass carousel, Wurlitzer band organ, the Museum of Fire History, as well as additional changing exhibits. For more information visit thecarouselmuseum.org

Related posts: