Shaker Museum, located in Mount Lebanon, NY, was lauded by The New York Times as being, “Widely considered the country’s most significant collection of Shaker furniture, objects, and archival materials.” And if you want to immerse yourself in this religious and production leader of all the Shaker sects, you will be glad to know at the beginning of August of 2023, a new location and building for this important Museum breaks ground in the Hudson Valley village of Chatham, New York. This forthcoming $18 million structure will be the permanent home for the Museum and will house the immense and diverse collection dedicated to the Shakers which is currently in storage and has been physically out of public view for over a decade but is available to view online at https://www.shakermuseum.us/collection. The Mount Lebanon Village is open and is a thriving living museum.

In June 2024, the museum opened a new library, archives, and administrative facility at 29 Jones Avenue in Chatham, NY. This addition complements the museum’s forthcoming permanent facility at 5 Austerlitz Street, which is currently under construction.

Lessons to be Learned

The overall mission of the Shaker Museum is to elevate “Shaker material culture to animate Shaker values and beliefs and inspire individuals and communities to deepen bonds and seek meaningful approaches to social, economic, environmental, and spiritual issues.” By sharing not only the material culture of Shakerism but also its teachings, Shaker Museum gives visitors the opportunity to immerse themselves into the what’s, how’s, and why’s of the lifestyle the Shakers chose to manifest.

Founder John Stanton Williams

Shaker Museum founder John Stanton Williams (1902-1982) began collecting items directly from the Shakers in the 1920s and 30s. He quickly realized the Shakers represented an important facet of American history and, as their societies were in decline, that crucial story was in danger of disappearing.

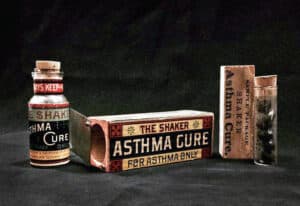

Williams embraced an almost “anthropological” mission to preserve what he could, traveling around New England to extant communities and forming lasting relationships with the Shakers. They came to trust him, not only to pay a fair price but to be the custodian of their story. Many collectors and dealers sought spectacular show pieces that could be resold, some of which are now on display in places like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, but Williams also wanted evidence of daily Shaker life, how they lived, and how they worked. The Shakers gave him important religious relics, such as a piece of Founder Mother Ann Lee’s apron, because they believed in his mission to start a museum and allow the Shaker story to live on.

Stanton built the museum in the dairy barn and farm buildings on his property in Old Chatham, New York. Before the Museum opened to the public, he’d acquired more than 4,000 artifacts. In 1948, he hired the Museum’s first curator and director, H. Phelps Clawson, who worked on installing displays and cataloging the collection. Williams continued to add to the collection, donated the land for the Old Chatham campus, and was closely involved in the Museum’s operations for decades.

Gathering the Collection

in a Shaker cloak. This and a photo taken from the back were used on labels and marketing materials.

The first benefactress of the Museum was Sister Emma J. Neale. Sister Emma came to live at the East Family of Mount Lebanon in 1855 at the age of eight and then moved to the Church Family where she lived for the next seventy years. In 1901, she became a trustee of the Mount Lebanon community and inherited responsibility for the community’s declining financial fortunes. She also managed the production of fancy goods made by the sisters and, in 1901, formed E. J. Neale & Co. which produced the popular Shaker cloaks. (Grover Cleveland’s wife wore a gray Shaker cloak at his second inauguration in 1893.) In 1930, she oversaw the sale of the church and Center Family properties, but still had the buildings’ contents to dispose of. Though the Shakers badly needed the funds realized from the sale of their possessions, John Williams was making a transition from collector to a kind of curator; he later stated that on several occasions she remarked, “Mr. Williams, you are really going to start a Shaker Museum.”

Through Sister Emma Neale, Williams acquired the first objects for the Museum, ranging from hand tools and pieces of equipment used in a variety of industries, to decorative art pieces such as baskets, oval boxes, and cupboards. Williams later remarked that without Sister Emma’s “faith and help, the job would have bogged down and perhaps been abandoned.”

Thanks to an endorsement from Eldress Emma B. King, the search for and gathering of key Shaker objects grew across all of the Villages. Soon after meeting Williams and Clawson regarding the building of the collection, a strong working and personal relationship grew between them. In a letter to Williams, Eldress Emma wrote, “… We feel you have been very fair to us in your dealings and unlike most museum promoters there is a sympathy and interest in what our organization represents and a desire to be helpful to us, while we contribute to your effort. This naturally calls for our regard and respect and a desire to be cooperative with you.” Thanks to this friendship, the Museum acquired hundreds of interesting and important artifacts.

Eldress Emma B. King corresponded regularly with both Williams and Clawson regarding important artifacts and items she felt would be well served as a part of the Museum. She would also reach out to most of the villages inquiring about pieces that were possibly being sold off or disposed of to determine whether or not they would make a useful addition to the Shaker legacy being gathered. For example, in a letter dated July 14, 1952, she wrote: “Have you any Shaker sewing desks at the Museum? If not I think I should reserve one for you before it is too late. They are in great demand and all we have left but two are needed and used by the Sisters here. I do not want to sell to any other party what you really need or want for the Shaker Foundation. I am museum minded and in due course of time may find other items which may be helpful to you.” Thanks to her networking, the Museum collection continued to expand.

Shaker sisters manufactured various styles of cloaks at villages in New York, New Hampshire, Maine, and Massachusetts. Modeled on traditional Shaker style, the cloaks became popular and stylish among non-Shaker women. First Lady Frances Cleveland is said to have worn a Shaker cloak to her husband’s second presidential inauguration. The sale of cloaks at Mount Lebanon earned the Shakers $144,700 between 1881 and 1929, over $3 million in today’s dollars. At Canterbury and Enfield in New Hampshire, the sisters ran a successful business manufacturing knit sweaters, which were often sold to colleges such as Yale and Dartmouth as “letter sweaters” in the school’s color.

Continuing to Grow

The Shakers transferred one of the most significant collections of their archival material to Shaker Museum – the records of the Central Ministry, which included diaries, business records, and correspondence spanning 150 years.

In 2004, the Museum became the owner and steward of the North Family site at Mount Lebanon Shaker Village, consisting of 11 shaker buildings on 91 acres.

The administrative offices, collection, and research library are located in Old Chatham, NY, where the original museum was founded. Here, researchers and scholars work and are given access to over 56,000 Shaker artifacts including tools, furniture, tools, photographs, textiles, and more. With the new building, access to the collection by the public will be much improved.

A Precious Item in the Collection

This framed piece of fabric was given to the Shaker Museum’s founder John S. Williams, Sr., in 1953 by Sister Marguerite Frost of the Church Family, Canterbury, NH. Williams’ son, Warden, recalled that his father was at Canterbury negotiating the purchase of a number of objects for the Museum. By this time some of the Shakers had become invested in and committed to helping him establish the Museum. At the end of the meeting, Sister Marguerite handed him a paper bag and told him not to open it until he got in his car. “Dad forgot to pick up the bag when he left the room and the Sisters had to come to his car and hand him the bag,” said Warden. When Williams had driven down the road a bit, he stopped the car and opened the bag to discover it contained a piece of fabric from the dress worn by Shaker Founder Mother Ann Lee on her voyage from England to America in 1774. Warden remembered that this moment brought his usually stoic father to tears.

The fabric has been identified as hand woven of hand-spun linen thread but has not been definitely dated to the period of the Shakers’ ocean voyage. While there is no reason to think the piece is not legitimate, its authenticity is of little importance. What is important is that the Shakers believed it was real and treated it as if Mother Ann Lee had indeed worn it aboard the ship Mariah sometime between May 10, 1774, when the small group of Shakers left Liverpool, and August 6, 1774, when they disembarked in New York City.

To learn more about the Shaker Museum, exhibits, activities, and collection, visit shakermuseum.us

Related posts: