by Maxine Carter-Lome, publisher

“It has happened more than once that a composition has come to me,

ready-made as it were, between the demands of other work.”

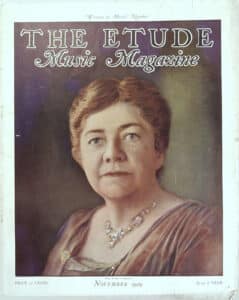

While you might not know her name, Amy Beach’s accomplishments in her day were a big deal – especially because she was a woman playing in a man’s world.

Shortly after Antonin Dvorak arrived in the United States in 1892 for a historic visit that resulted in the creation of his “New World” Symphony, he made a cursory remark to a Boston newspaper about gender and the field of music.

“Here all the ladies play,” Dvorak said. “It is well; it is nice. But I am afraid the ladies cannot help us much. They have not the creative power.”

His contention that women might play but not create—that they could be performers, not composers—was commonplace at the time. Ten days later, though, another paper published a rebuttal from an up-and-coming Boston composer named Amy Beach, who would soon go on to prove Dvorak wrong.

“From the year 1675 to the year 1885, women have composed 153 works,” Amy Beach wrote. “Including 55 serious operas, 6 cantatas, 53 comic operas, 17 operettas, 6 sing-spiele, 4 ballets, 4 vaudevilles, 2 oratorios, one each of fares, pastorales, masques, ballads, and buffas.”

The question is, who was Amy Beach to comment on such matters?

Amy Cheney, Child Prodigy

Amy Marcy Cheney was born on September 5, 1867, in Henniker, New Hampshire, the only child of a prominent New England family. Her mother, Clara Imogene (Marcy) Cheney, was a talented amateur singer and pianist, her father, Charles Cheney, owned a paper mill.

Amy was a true prodigy who, according to her biographers, memorized forty songs at the age of one and taught herself to read at age three. At age four she played four-part hymns and wrote her first compositions with Clara’s help, including a little piece for piano entitled “Mamma’s Waltz.” By the age of six, she began studying piano with her mother and performed her first public recitals one year later, playing works by Handel, Beethoven, Chopin, and some of her own pieces.

As with her musical training, Beach’s academic education was also home-centered. Her mother taught her at home for six years. She then attended a private school run by W. L. Whittemore. Beach particularly enjoyed natural science and languages like French and German. While she was encouraged academically, it was within the limits of what was expected of young women in this period.

In 1875 the family moved to Boston, where Amy studied with the leading pianists of her day, including Ernst Perabo of the New England Conservatory and Carl Baermann, a pupil and friend of Franz Liszt.

In 1884, at age 16, Amy gave her first public recital in Boston. A year later, she performed the Chopin Concerto in F Minor with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, with Wilhelm Gericke conducting.

Although Beach admired her mother and owed her an enormous debt for nurturing her career, biographers describe Clara as “rather repressive” and “controlling.” The same could also be said for the man Amy chose to marry.

Mrs. H.H.A. Beach

On December 2, 1885, Amy married Dr. Henry Harris Aubrey Beach (1843-1910), a physician, Harvard University lecturer, and amateur singer who was 24 years her elder and a widower. He had followed her career from the time she was a child in part because he was also a musician, albeit on an amateur level.

One of the conditions of their marriage was that Amy stop working as a piano teacher and restrict her public performances to two a year, with the profits donated to charity. Dr. Beach wanted a wife, not a concert pianist. Amy agreed but wrote: “I thought I was a pianist first and foremost.” He did, however, encourage her to work as a composer. A dutiful wife, Mrs. Beach channeled her musical energies into composing and became known publicly and professionally as Mrs. H. H. A. Beach. For many years, Amy held weekly musical soirees at their Commonwealth Avenue home, during which she encouraged other composers and performers. The Boston Classicists Arthur Foote, George Chadwick and Horatio Parker welcomed her as “one of the boys.”

A Self-Taught Composer

Amy’s husband’s restrictions on public performances and his belief that formal study might inhibit her originality required that she become a virtually self-taught composer.

Beach had received one year of formal training at the age of 15 when she studied harmony and counterpoint with Junius W. Hill (1840-1916), an organist, composer, and Professor of Music at Wellesley College. With that foundation, she went on to study music theory, counterpoint, musical form, and instrumentation on her own. She studied Bach’s fugues by writing out her version of one of his works then comparing it to the original, and taught herself orchestration by writing notations of themes she heard at concerts, looking at the original score, and then putting the versions side by side.

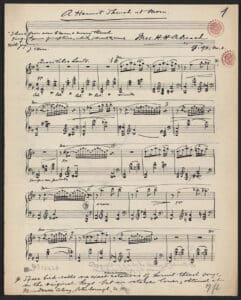

Beach’s first works were poems that she liked, set to her original music. Her first published piece while studying with Hill was a song to the poem of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s The Rainy Day.

While she would continue to do these kinds of pieces throughout her career, Beach would go on to do much larger and more complex pieces including major orchestral works, choral works, chamber works, church music, and cantatas.

Beach’s Work Hits the Stage

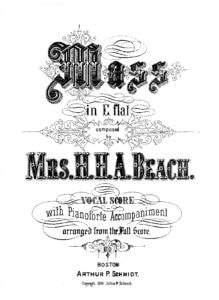

In 1892, Beach’s first major work was performed, Mass in E-flat Major, numbered Opus 5. It was a 75-minute piece written for chorus, vocal quartet, soloists, orchestra, and organ. The mass was performed by the Handel and Haydn Society with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. This marked the first time a composition written by a woman was performed by these groups. One modern-day critic calls Beach’s Mass in E-flat Major, “a colorful, dashing work.”

That same year, Beach had her second work performed, an aria entitled Eilende Wolken, Segler der Lüfte (Wand’ring Clouds, Sail through the Air) for contralto and orchestra, based on Friedrich von Schiller’s Mary Stuart. Beach was asked to write this for Mrs. Carl Alves, who had been the alto soloist for the premiere of Mass in E-flat Major. The first performance of Eilende Wolken was given by the Symphony Society of New York. Again, this was the first work arranged by a woman to be performed by this group.

Beach went on to write Festival Jubilate, op. 17 for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, and Song of Welcome, op. 42, commissioned for the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition in Omaha. But it was Beach’s “Gaelic” Symphony, which premiered in Boston in 1896 with Emil Paur conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra, that shattered the glass ceiling. Gaelic was the first symphony to be composed and published by an American woman.

Beach’s Gaelic Symphony was not taken seriously by critics at the time due to her gender. Compared to Dvorak and Chadwick, Beach’s music was described as “delicate,” “beautiful” and “tender.” It was striking that many of the quotes, whether positive or negative, couldn’t help but mention Beach’s gender in relation to the music, while “the most negative critics displayed heightened anxiety over the emergence of a truly valid American symphonic voice capable of speaking to international audiences.” This is what people had been hoping for in the “great American symphony;” however, for some, the fact that this voice was coming from a woman was the sole thing rendering the attempt invalid.

Despite the critics, the premiere of Beach’s symphony established her as a major American composer, and Gaelic, the most successful American symphony by any composer of Mrs. Beach’s generation. Despite the fact that she was a woman in a man’s profession and composing in a male-dominated genre, she proved that a woman can be just as talented and successful as any male composer.

A Second Act

In 1910, Dr. Beach died, followed by Amy’s mother. To recover from their deaths, and to establish her reputation there as both a performer and composer, Beach sailed for Europe and began performing across the continent. She received enthusiastic reviews for recitals in Germany and for her symphony and concerto, which were performed in Leipzig and Berlin.

When World War I broke out, Beach was forced to return to the United States in 1914, settling in New York City, which remained her home base for the rest of her life. After her return, she toured as a pianist and continued composing, and started giving music lessons again.

In 1921 Beach became a fellow at the MacDowell Colony in Peterborough, New Hampshire, where she composed most of her later works. MacDowell was founded in 1907 by composer Edward MacDowell and his wife, pianist and philanthropist Marian MacDowell, as an artists’ colony. For her time at MacDowell, and in support of its mission, Beach left the MacDowell Colony her royalties in her will, helping to support future generations of artists of all forms.

Almost all of Beach’s more than 300 works were published soon after they were composed and performed. Beach died of a heart ailment in New York City on December 27, 1944, at the age of 77.

CODA

Throughout her career as a musician and composer, Beach assumed many leadership positions, often in advancing the cause of American women composers. She was associated with the Music Teachers National Association and the Music Educators National Conference. In 1925, she was a founding member and first president of the Society of American Women Composers, earning her the historic designation as dean of American women composers. Her accomplishments also made her a national symbol of women’s creative power as American music entered the 20th century.

Amy Beach is experiencing a renaissance of sorts as music historians and composers look to the past for inspiration and find the door she opened for future generations of women composers. In 1994, two books on Amy Beach were published by Walter S. Jenkins and Jeanell Wise Brown, with a more recent book published in 1998, Amy Beach, Passionate Victorian: The Life and Work of an American Composer, by Adrienne Fried Block. These books have led to a reprinting of her music and renewed examination of her work through a less gender-bias lens. And it holds up!

In her day, critics praised her “deeper resources of the science of music” that were “difficult to associate with a woman’s hand.”

Her thoughts on the matter?

“Music is the superlative expression of life experience, and woman by the very nature of her position is denied many of the experiences that color the life of man.”

Despite all the restrictions and limitations of the day placed on her as a female musician and composer, Beach was able to break through the gender barriers of the Victorian Era and get her voice heard, perhaps lamenting but ultimately accepting her prescribed role as a woman and wife. Over 75 years later, we are still listening and her work speaks for itself.

Related posts: