By The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation staff

A version of this article first appeared in the winter 2021 issue of Trend and Tradition.

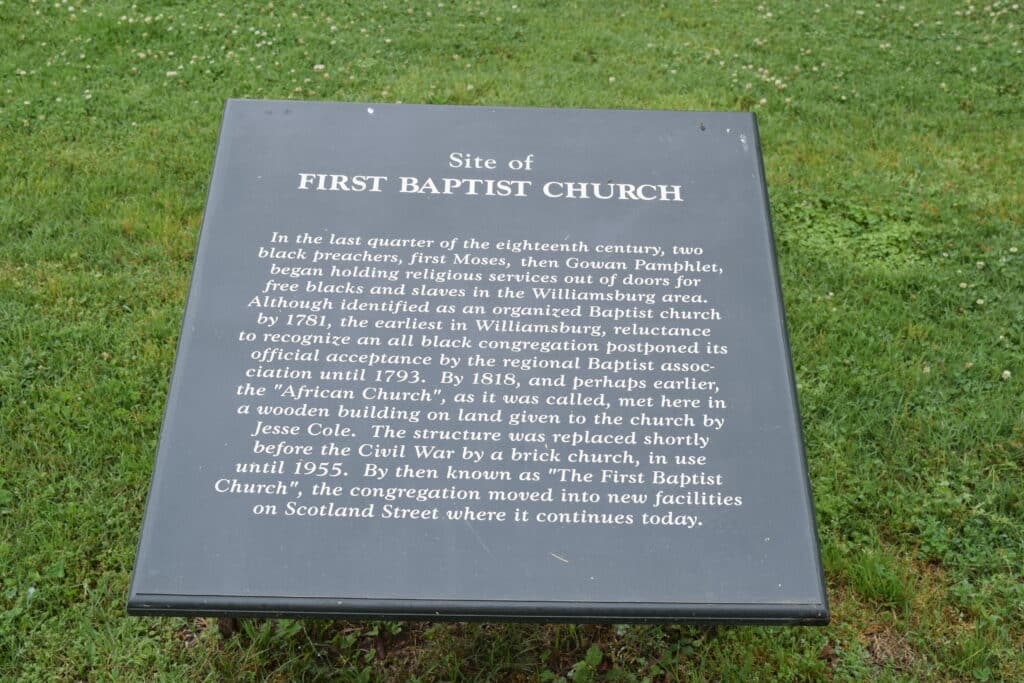

Connie Matthews Harshaw was driving on Nassau Street when she passed a grassy field in which a gray marker had been placed. The words “Site of FIRST BAPTIST CHURCH” indicated where the church’s first permanent location had been.

There is no building to visit. No other information was given at the site. The 1856 brick church that once housed the Williamsburg congregation had been purchased and torn down in the 1950s during the process of restoring the colonial capital. The First Baptist Church then moved to a new home several blocks from its original site.

Back Up to the Beginning

But the First Baptist Church’s story doesn’t begin in the 19th century. It begins in the 18th century, in a brush arbor. At that time, a brush arbor was a rough, open-sided shelter constructed of vertical poles driven into the ground with additional long poles laid across the top as support for a roof of brush, cut branches, or hay. Appearing in the 1700s and early 1800s, brush arbors were used by some churches to protect worshipers from the weather during lengthy revival meetings. Free and enslaved Black congregants were hidden from view because they were forbidden to gather in groups.

The bulk of the Church’s history, though, emerged on Nassau Street where the group eventually moved after a white landowner, Jesse Cole, offered them land in town on which to worship. According to oral history, Cole heard the music of the congregation and was moved to offer them sanctuary.

Just as that early congregation was first hidden from view, so was the church’s history. When the church moved to its 20th-century home, the antebellum-era brick structure built on Cole’s property was torn down, and the site was paved.

As Harshaw looked at the empty site and the grassy field, she wondered: Where is the story that goes with the marker?

A Mission is Configured

“I see a sign there that says this was the site of the oldest church created by and for African Americans – and that’s all. There was no story,” said Harshaw, a member of the First Baptist Church and president of the Let Freedom Ring Foundation, which is dedicated to preserving and telling the church’s story.

Shortly after Cliff Fleet became president and CEO of Colonial Williamsburg, he invited Harshaw to breakfast. They talked about the restoration and Colonial Williamsburg’s history with the First Baptist Church. And they talked about the sign. Harshaw said Fleet’s reaction was the same as hers.

What followed was a plan to try to find—and tell—that story.

Some of that story was preserved under the pavement, waiting to be found. The effort to unearth clues began in September 2020 when the pavement was removed and Colonial Williamsburg’s archaeology team—in collaboration with the church—began the excavation to find the evidence of one of the oldest Black churches in America.

“There is a story there,” Harshaw said as the excavation project began. “The fact that they’re looking, that they’re trying to uncover that story – that is major for us.”

“We’ve got to acknowledge the painful past, but it fortifies us,” she said. “And we’ve got to look to the future. This is the first step – the project on Nassau Street.”

Church Leaders Lost, then Found

The First Baptist Church story begins in 1776, when the church was organized. It was originally led by an African American named Moses and then by Gowan Pamphlet, an enslaved Black tavern worker who by 1793 saw his congregation accepted into the Dover Baptist Association of Virginia. The congregation moved from the arbor to Cole’s property, where they built their first permanent building referred to as the Baptist Meeting House in an 1818 tax document. A tornado destroyed that structure in 1834.

Then came the brick church dedicated in 1856, which was known before the Civil War as the African Baptist Church. It was renamed the First Baptist Church in 1863.

James Ingram remembers when he began to interpret Gowan Pamphlet in Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area 22 years ago.

“I was given about two paragraphs, and it was all we knew about Gowan Pamphlet,” he told an audience that gathered in early September for a prayer vigil held at the Nassau Street site just before the archaeological excavation began. In the last sentence of the second

paragraph, he learned that Pamphlet had sought to have his church accepted into the all-white Dover Baptist Association, which at the time was one of the largest district associations of Baptists in the world.

Ingram was stunned. He had studied religion at two seminaries and had never heard of Gowan Pamphlet. Now the man who portrays Pamphlet dreams of finding the foundation of the structure where the ordained Black minister preached.“I think we have something to talk about here,” he said.

Excavation Begins

This is not the first archaeological project at the Nassau Street site. A dig in 1957 also searched for—and found—the existence of earlier structures, but no connection was made at the time between those structures and the Church.

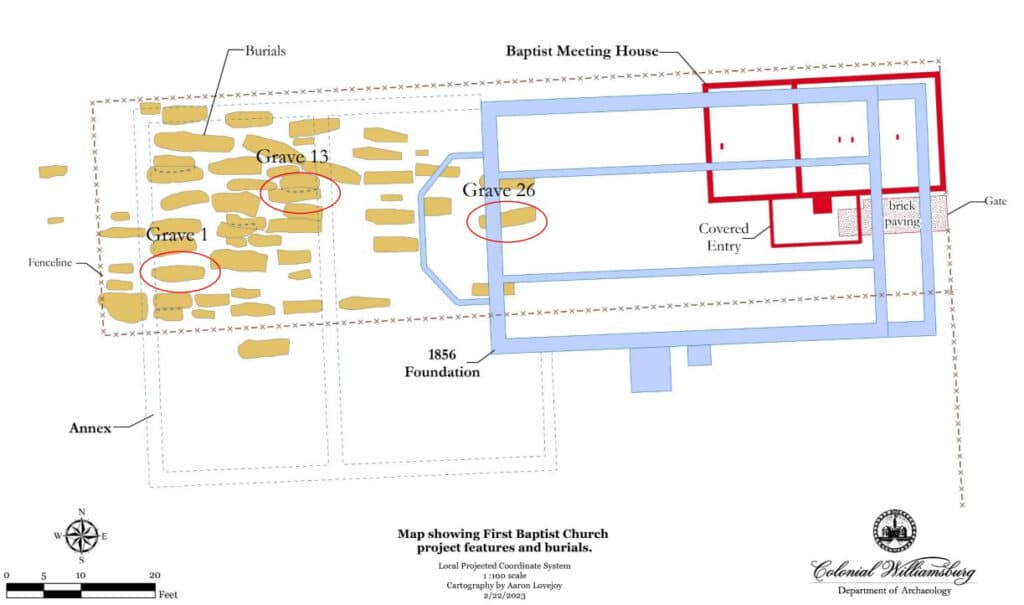

Colonial Williamsburg Director of Archaeology Jack Gary and his team studied notes and maps from that early excavation to determine the first steps in the project. Before ground was broken, ground-penetrating radar showed evidence of a structure, which gave the team a starting point.

In October 2021, after a year of excavation, Gary and his team announced the discovery of a small brick building foundation that sat alongside a brick paving and on top of a layer of soil that dated to the early 1800s. In addition to the foundations of buildings, the team found what appeared to be steps and brickbats, which may have indicated a path to the street.

Additional archaeological evidence, including an 1817 coin and a straight pin discovered under the paving, indicated that the foundation was constructed sometime in the first quarter of the 19th century. Tax records suggest that by 1818, the congregation was worshipping on the site in a building known as the Baptist Meeting House, and, in all likelihood, the congregation’s first permanent structure.

The Congregation Links to its Past

“The early history of our congregation, beginning with enslaved and free Blacks gathering outdoors in secret in 1776, has always been a part of who we are as a community. To see it unearthed—to see the actual bricks of that original foundation and the outline of the place where our ancestors worshipped—brings that history to life and makes that piece of our identity tangible,” said Dr. Reginald Davis, pastor of the First Baptist Church.

Over the course of the excavation process, archaeologists also discovered a total of 63 burials on the site. At the request of the First Baptist Church descendant community, archaeologists excavated three grave shafts over the summer of 2022, launching an extensive process to unearth information about who was buried there and the lives they led.

In April 2023, experts from Colonial Williamsburg, William & Mary, and the University of Connecticut presented the results of the archaeological, osteological, and DNA analyses of three burials excavated at the site of the church’s original structure. Combined, the evidence confirmed that the individuals buried there are the ancestors of the First Baptist Church community, which extends well beyond the current Scotland Street congregation.

“This is what we were praying that we would hear,” said Harshaw. “To know for certain that these are our people and that this was our congregation is such a powerful step forward in the ongoing work of reconstructing our history and telling a more complete story.”

Let the Analysis of the Discoveries Begin

While the excavation of the site is now concluded, the work continues. Archaeologists will now turn their attention to the lab where they

will analyze the over 200,000 artifacts found at the site in search of additional clues about the lives of the people who worshipped there.

Taking control of their story is important to Davis and his congregation. He and his parishioners want to know more about the people who persisted in the pursuit of their faith.

“These are people who never gave up on their God,” he said. “They never gave up on their country. We have to look back to gain wisdom.

“We want to help tell the story of people who were brought here … and in spite of it all, people who wanted to be part of this democracy. They want equality under the law. We want what America has to offer. That’s why people come here.”

The Foundation plans to reconstruct the original church structure and open it to the public by the fall of 2026 to coincide with the 250th anniversary of the congregation’s founding in 1776. When it opens, it will not require an admission ticket to ensure that this vital piece of the First Baptist Church community’s story remains accessible to all.

“The history of this congregation is a story that deserves to be at the forefront of our interpretation and education efforts,” said Fleet. “We are honored to play a part in bringing that story to light.”

Evaluating History

From start to finish, the First Baptist Church project followed the lead of the contemporary First Baptist Church congregation and the broader descendant community.

Bobby Braxton, former city councilman and longtime community activist, said he made near-daily visits to the Nassau Street site as the work

progressed so he can see the discoveries for himself. His interest is understandable. He also serves on the First Baptist Church’s history committee.

“I don’t understand [the archaeologists’] business, but they get so much excitement about it, and when they explain it, you get caught up in it too,” Braxton said. “To say it’s exciting – that’s putting it mildly.”

Harshaw said families who have long been members of the church are especially involved in the project. “One of the things we’ve done for Nassau Street is involved the descendant community,” Harshaw said. “What do you want the nation to know about this sacred space?”

The excavation comes at a pivotal time in the American conversation about race. Harshaw and Davis see an opportunity to contribute to that conversation.

“Right now, as we talk about the timing for this, there is no better time in history than now to do this,” Harshaw said. “This is a national treasure. It’s not just a church. It’s something that should be shared with the nation.”

Sharing the church with the nation also means sharing an uncomfortable chapter in the country’s past. But without confronting it and acknowledging the wrongs of slavery, Davis said, there can be no reconciliation.

“We have not gotten rid of ghosts of the past,” he said. “We want to move to a future that is bright. The beauty of adversity is something that ought to be celebrated not tolerated.”

Related posts: