By Matthew Webster and Dani Jaworski

When studying the building history of 18th-century Williamsburg, architectural fragments have proven to be valuable and fascinating research tools. Since the 1920s, architectural fragments associated with Williamsburg, Virginia were actively collected and studied. With the core collection pertaining largely to the Williamsburg, Virginia area, the collection also has important fragments from New England, the Mid-Atlantic, and Southeast United States, as well as the Caribbean and Europe. The collection is comprised of over 15,000 fragments and has everything from roof framing and carved decorative elements to nails, plaster, and wallpaper.

Some of the earliest fragments discovered and collected were from the Bruton Parish Church, circa 1715. The 1752 pilaster capitols, panels, and even the large round window from the east chancel were found in the cellar of a Williamsburg house in the 1920s. These fragments presented information and evidence used for the restoration of the church to its 18th century appearance, and now are part of Colonial Williamsburg’s architectural fragments collection.

The fragments collection has been instrumental for both the understanding and the reconstructing of Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area. In 2008, the Foundation began the reconstruction of the 1750s Charlton Coffeehouse. At the core of this effort were over 200 fragments from the original structure. Found in the cellar and reused in the house that replaced the Coffeehouse in the 1880s, these fragments included window sashes, doors, moldings, nails, rafters, joists, and many other elements.

With careful study, these items established information on everything from the pitch of the roof, arrangement of the chimneys, width of floor boards, the types and length of nails used, molding profiles, paint colors, and even the presence of wallpaper. These elements were meticulously copied for the reconstruction, with the surviving fragments serving as models.

Following the Evidence

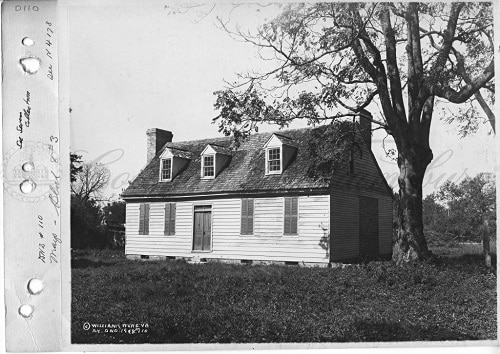

Many of the collection’s fragments are the last remaining pieces of structures lost to time. A lone baluster in the collection was thought to be the only element remaining from the circa 1767 Mayo House (named after its last owner). Located on York Street (just east of today’s Historic Area boundary), the house was built for one of the first owners of the property, Thomas Powell, a noted surgeon. His widow deeded it to their son Thomas Powell, who was also a surgeon, on April 17, 1767, mentioning it as “the new dwelling house.”

While conducting research on the Mayo House, an image was discovered from the Colonial Williamsburg Special Collections that showed the original stairs still in place in the dilapidated building. In the image, an empty space near the top of the balustrade shows where the baluster in the collection was removed. After undertaking further research, it was able to be determined that not only was the baluster in our collection the one missing in the picture, but that the rest of the staircase had been reused in the George Pitt House, a building that was reconstructed in the Historic Area in 1936.

When the staircase was installed in the George Pitt House, it was stripped of all its early paint. The removed baluster had remained protected in the fragments collection, retaining all of its 18th century information. Paint analysis from the single baluster detected seven finish layers: the earliest has a clear primer coating (possibly shellac), followed by a greenish-blue paint. The unaltered baluster allowed us to understand construction techniques, design aesthetics, and paint colors used in Williamsburg around the time of the American Revolution, and serves as an invaluable link between a lost 18th century Williamsburg house and a reconstructed one in the Historic Area.

The fragments are not only parts of buildings, but have links both historically and through the use to their owners. A circa 1753 window pane from Bassett Hall, the circa 1753-66 house that was the part time home of John D. Rockefeller Jr. and his wife Abby Aldrich Rockefeller during the early years of the restoration, highlights the Coke and Henley families. They lived in a few of the surviving colonial houses including the Coke-Garrett House, the Charlton House, and the aforementioned Bassett Hall.

On the pane, two names were etched: cousins Mary E. Coke and Clarissa W. Henley. Mary was the daughter of John Coke who owned Bassett Hall from 1843 to 1845. Clarissa was the daughter of Leonard and Harriett Coke Henley who owned a house on Duke of Gloucester Street (today referred to as the Charlton House) from 1819 through 1880. Mary’s father and Clarissa’s mother were brother and sister. We believe that the cousins etched their names in the pane during the time the Cokes lived at Bassett Hall, when Mary and Clarissa would have been in their mid-to-late teens. While the historic record can link the families to the house, it is the window pane that clearly shows the two cousins visiting each other, creating a strong connection of person and place.

A Family Feud

Other fragments represent stories far beyond the structures they belonged to. A cornice from Tazewell Hall, circa 1762, is such piece. The house was moved out of Williamsburg in the 1950s, and with it, part of the story of a family’s struggle during the Revolution.

Tazewell Hall stood a few blocks south of courthouse green, just outside Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area. The cornice fragment from the home witnessed the story of two brothers, one a patriot and the other a loyalist during the Revolution. Tazewell Hall was the home of John Randolph, who remained loyal to England during the Revolution, eventually fleeing Virginia for

Scotland. His brother, Peyton Randolph had a home on the opposite side of courthouse green. Peyton was an ardent patriot, becoming the first and third president of the Continental Congress. This fragment is one of only a few physical elements remaining related to John Randolph at Colonial Williamsburg.

All of our fragments represent structures and the people who built and used them. While it is impossible to prove, many of the fragments likely represent people who do not survive in the written record. Their stories are left as marks from the production and construction of the elements and the structures they belonged to. Several fragments tell these stories.

When the Governor’s Palace burned in 1781, the cellar floor was buried and eventually found intact when the site was excavated in the 1920s. While most of the pavers remain in their original locations today, a few were removed. The pavers are remarkable fragments from a historically important structure. There is however, more to them than just their connection to the Palace. On the unfinished side of many pavers, markings are carved. These markings represent the unknown 18th century English stone workers who made the pavers. The marks assured that the pavers were attributed to the correct workers, as they were paid based on what they produced.

Bricks from the 1750s Charlton Coffeehouse mentioned earlier gave information on the size and color of the bricks used, and guided us in their reproduction. Marks from the brick molds, scraping off excess clay, and burn marks give us information on their 18th century production. A few brought us even closer to the unknown brick makers. Looking closely, the fingerprint of a worker can be seen in one brick. While picking up the molded clay brick before it was completely dry, the worker’s fingerprint was transferred into the clay. Surviving the firing process and used in the construction of the Coffeehouse in the 1750s, the brick was uncovered over 250 years later, with its maker’s legacy imprinted on it.

We also see the marks of animals on the fragments. One brick from the Coffeehouse has a dog paw imprinted in it. The dog walked across the area where the brick was drying, and with one misstep, its story was imprinted in the historic record. Still usable, the brick was fired and used for construction.

Animal Behavior

The presence of many different types of animals is evident in the collection. Perhaps the most compelling example of this was found at the 1738-1745 Wetherburn’s Tavern.

Rats were an unwelcome, yet inevitable part of life in the 18th and 19th centuries. They made their homes in walls, between floors, and any other space they could get into. The rats that lived in these houses are a particularly social variety that occupy a single nest for several generations as long as food is present.

While the thought of rats in buildings is not comforting, for researchers their nests often offer a treasure trove of information. The black rat is a hoarder and generally ranges no more than 150 feet from its nest. Black rat nests have yielded fragments of 18th century wallpaper, documents and newspapers, pieces of furniture, ceramics, bone, grain, textiles, shoes, and even silver utensils. These objects are datable and give us a snapshot of life within a 300 foot diameter space from the nest.

Rat nests found in the ceiling of Wetherburn’s Tavern have given us perfect snapshots of life inside the tavern before, during, and after the Revolution. Providing a unique form of documentation, the nests contained sections of newspapers, grass, small bits of cloth, scissors, an iron cup, metal strips with brass ends, a wheel, a spool of thread, a shell, gown stays, a fork, stoneware ceramic fragments, nails, and many other fragments. These items have been dated from the mid-18th through the early 20th century. While a surviving 1760 inventory of Wetherburn’s Tavern tells us about what was in the building at that time, the rat nests give us insight into what people used on a day-to-day basis in the building up through the early 20th century.

These fragments are tangible links to our past, serving as relics, invaluable research tools, and memorials to those who made and used them. Every fragment has a story to tell creating a better understanding of our past.

Today, Colonial Williamsburg only removes architectural elements when they or the structure is threatened. The fragments that make up the collection are like any other collection at Colonial Williamsburg. They are carefully curated, cataloged, maintained, and studied. Exhibits such as Architectural Clues to 18th Century Williamsburg, Rebuilding Charlton’s Coffeehouse, and Rich and Varied Culture: The Material World of the Early South at Colonial Williamsburg’s DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, showcase elements from the fragments collection.

Matthew Webster is Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s Director, Grainger Department of Architectural Preservation and Research, and Dani Jaworski is the Associate Curator of Architectural Collections.

Related posts: