by Judy Gonyeau, managing editor

On the left, is a delicate portrait of a beautiful young girl. She may look a bit on the yellow side – what some may call a yellowing of the portrait due to age has taken away some of the finer features. Parts of the canvas are missing, and this painting is not stable enough to last through the next couple of generations.

On the right, the young girl appears refreshed, healthy-looking, and soft yet wise. The vignette effect is complete with nothing to disturb the viewer’s eye from enjoying this painting as it was intended, thanks to careful restoration.

Fine Art Restoration is so much more than cleaning and touching up the paint. It is making a full list of discovered weaknesses, whether due to varnishes, the frame, paint loss, or past not-too-great restorations. Restorer Julian Baumgartner demonstrates the tasks necessary to make what is beautiful, whole once again.

Meet YouTube sensation, Julian Baumgartner, a second-generation fine art restorer renowned around the world for his amazing restoration work, yet a bit controversial for his approach and belief that the restorer is the preserver of the artist’s work. As Julian stated, “I work in service of the image.”

The delicate work done by Baumgartner is mesmerizing to watch and to listen to, allowing the viewer to appreciate the artwork even more than thought possible thanks to his YouTube channel: www.youtube.com/@BaumgartnerRestoration

The viewer is taken through the restoration process as agreed upon by the owner of the artwork and Baumgartner. After assessing the work, a conservation proposal is sent to the client, outlining what discovered issues need to be addressed, the timeline for completion, and the price. Some work is completed within one week while others require several weeks depending upon the complexity of the work to be done.

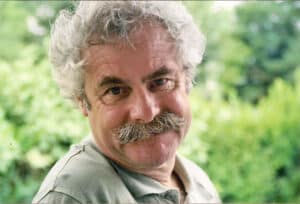

Baumgartner Fine Art Restoration was established by Julian’s father, R. Agass Baumgartner, who was born in Switzerland where he received an intensive art education. Julian learned by first being placed in his father’s studio while a youngster, and moving on to his own art education. However, nothing compared to learning by working with and watching his father, a master at his calling, at work.

Agass passed away in 2011 at the young age of 63. As remembered by a patron and friend, he is described as the following:Agass was a wonderful, cheerful man and a remarkably talented conservator. He always had time for us small collectors/ enthusiasts; he was eager to talk about the art, the physical facts of a piece, historical clues, and evidence, even the artist; he was an educator in his own way; but above all, he was a gentleman artist himself, who honored the labor of artisans long gone by attending to their canvases.”

His joyous approach to art is continued by his son, Julian, who is determined to reveal the image as it was originally intended, and return it to its owner strengthened, allowing it to be enjoyed for generations. Whether applying his skills to an old master or an amateur artwork, he approaches each one the same – with care.

The Interview

Would you mind sharing how this business became established? How did you get into the family business?

I often joked that my entrance into the world of conservation was through indentured servitude. My father started this business here in Chicago after working as a conservator and with conservators in both Switzerland and France in the late 1970s. As a child, I would often spend weekends and sick days and summer vacations at my dad’s studio mostly getting into trouble and trying to stay out of his hair. What I was unaware of was the fact that I was slowly learning the craft and trade by watching him. Throughout college I worked for him mostly sweeping floors and organizing the studio and then after graduating I began a formal apprenticeship which generally included getting a lot of coffee and getting yelled at a lot. But for the next five or six years I worked under him watching, studying, reading, absorbing, and learning everything that he could teach me and supplementing it with any source material I could find.

When it comes to fine art, how do you know what is worth restoring? And with some not-so-fine art?

Well, it’s not really up to me to make that decision about whether or not a piece is worth restoring. That is a burden that falls on the

owners, luckily. That said I do try to offer some contacts for my clients; obviously, if they are looking to sell the piece there is a cost-benefit analysis, and putting in money that they cannot realize during the sale wouldn’t be wise. It gets a little bit more difficult with heirlooms and general pieces that are loved because the cost of conservation may not equal the “value” of the piece.

Ultimately though, most people who do inquire about conservation are interested in some level of work and there’s always a solution

that can be found – even if it’s not a comprehensive conservation and restoration.

You use several basic tools to physically approach repairs (except for your amazing, heated table!). It can be hard work. But I enjoy hearing how you pace yourself when you do the work. Do you have a particular routine you follow? Do you ever work on more than one project on the same day?

Over the course of 2+ decades, I have learned and developed a very structured routine for how I approach paintings and the work in the studio; it’s necessary to keep a schedule and workflow and to keep everything organized and not lose focus. I will work on many paintings at the same time and paintings that require a variety of treatments so that I have a mix of work throughout the day and week. As an example, I will only choose a few paintings that need a lot of retouching so that I don’t spend the entire week sitting and retouching because it’s quite laborious and exhausting. Having a mix of pieces not only keeps my skills sharp but also keeps me engaged in what I’m doing and ensures that I don’t become bored or complacent with any steps or projects.

What are the differences when working on a large tour de force vs. a tiny masterpiece?

Nothing really. Every project requires the same amount of focus and attention to detail and if it’s a small painting it may take less time than a large painting but that doesn’t mean that it’s an easier project or one that can be dismissed in any way, shape, or form. But, with very big projects either in scale or scope, we approach them as one would anything of that scale; one incremental step at a time and we don’t focus on the finish line, rather we focus on the immediate task at hand and that allows us to move through the project without becoming overwhelmed.

You once discussed using different paints on a piece. How do you determine what type of paint to use when doing touch-ups?

Every treatment we do that requires the addition of materials is evaluated based on what is best for the painting. Some pieces require different paints for retouching because the artwork cannot sustain exposure to certain solvents or materials and as such, we choose an alternative. In addition, some adhesives that require heat may not be suitable for heat-sensitive paintings and as such we will choose a

cold-set adhesive. Evaluating the best course of action is essential as the first step in any project and that will become the guide for all the work we do on that piece.

What is the oldest piece you have restored? The youngest?

I think the oldest piece that I have worked on dates back to the early 1400s or late 1300s and the youngest was still wet from the artist’s studio. Believe it or not, the 600-year-old painting was exponentially easier to work on than the six-day-old painting.

What is the toughest thing to match?

Ask any conservator and I would wager the answer would be the same; flat solid color fields where there is no texture no visual static or anything that allows camouflaging the retouching. These colors change based on the light and time of day and the sheen changes based on your viewing angle and all of these things conspire to make that type of retouching incredibly difficult.

I notice you seem to approach each work as a total project based on your assessment. What do you look for when you assess a painting?

Ultimately, I try to see if I can effect a positive change on the work and if that is possible then it’s a candidate for conservation. Between the needs and wants of the client, the needs and wants of the artist, and the artwork, as well as those of the conservator, there is a sweet spot where, if all of those sometimes differing goals and objectives can be met, we have a successful project.

In the “About” section of your website, it is said that Baumgartner has chosen to stay relatively small. How many pieces do you take on over the course of a month or year?

I suppose that is a relative statement because while it is only me and my assistant, we still take on approximately 800 pieces a year. Not all of these projects are approved and not all are completed in the same timeline, but it keeps us quite busy.

Your YouTube channel is insanely popular, and goodness knows people love before/after stories. As of this moment, you have 1.75 million subscribers. Why do you think your channel has taken off?

If I had the answer to this question I would sell it in a bottle! I think it’s a confluence of several factors; people love seeing transformations whether it’s a home being renovated or a makeover; it feels good to see something go from a dilapidated state to a glorious one. In addition, watching craft and somebody who is fully engaged in their craft is a very seductive and calming process, I feel the same way when I watch This Old House or cooking shows. And then of course the world of art is largely kept at arm’s length from the general public and getting a peek behind the curtain into a location that has four generations existed only in secret is kind of magical.

What are some indicators of the age of a painting?

We can of course start with the subject matter; a portrait will tell us a lot about the time from the clothing and hairstyles of the sitter. Then we can look at the materials and often times we can deduce an approximate age based on the construction or the materials used. When all of those fail and determining an age is critically important, we can turn to scientific analysis and things like radiocarbon dating to give us a better indication.

I noticed in the video that you were doing the complete work from start to finish. Are there times when you allow others/colleagues to work on projects with you? Or someone to assist?

Aside from my assistant, no I don’t outsource or subcontract any of the work.

Do you have someone set up your table to begin the process or do you take care of mixing what you need for solvents, varnishes, etc.?

Again, for the past decade-plus it was only me and only recently do I have an assistant so no, I don’t require or depend upon somebody else preparing or setting up my workspace before I work. It’s critically important to me that I am in control of, or aware of the entire process from start to finish. This work isn’t easily delegated or segmented and being aware of and in control of everything throughout the process results in a better outcome.

Have you worked on modern works that have been damaged?

I’ve worked on all types of pieces from old masters to contemporary works and everything in between. Each painting has a unique set of complications and requirements that can make the conservation appear easy yet be very difficult. I generally find that more modern and

contemporary works are more complicated to conserve because of unique materials or unorthodox creation methods, but that presents opportunities for growth and innovation that make this work so exciting.

Do you ever work from photos of a painting taken before they were worn/damaged?

There are rare instances when there is good enough documentation of an artwork before the damage that we can use as a reference. When those cases arise it’s a real pleasure to have a data point that we can use during the conservation and restoration of the work. Unfortunately,

it’s quite rare, and even when there are photographs they may not be suitable for our use.

How can our readers help preserve their purchased artwork? Acrylic? Oil? Watercolor? Other?

The best advice I can give to collectors is to do nothing to their artwork. Don’t try to clean it, don’t try to work on it, and don’t do

anything that could potentially jeopardize its stability. Make friends with a good conservator and slowly work through your collection

heeding their advice and methodically approaching each project.

On a personal note, I have a painting created by my father when he was 12 – painted on cardboard. Amazingly it has stayed in great shape over the past 70+ years. Materials used for paintings can range from papyrus to board to paper to canvas, and cardboard!

There’s that saying about old houses and how they don’t build them like they used to. The same applies to artworks. Old master paintings were made with care and techniques that have stood the test of time. Contemporary works are often built less well, and this will have a deleterious effect on them in the future. Good quality materials, archival materials, and proper art-making materials all contribute to the success and longevity of a particular artwork.

Re: Varnishes – what are the better ones to use that will last, and what should painters avoid?

Artists are very fortunate today that there are many modern and synthetic residences that are ultraviolet stable and easily removed, unlike the natural reasons of yesterday. I generally tell artists to avoid using shellac and damar because they are fallible, and we know that there are better alternatives. Gamblin makes a wonderful varnish called Gamvar based on a commonly used synthetic resin within conservation that is very stable, very easy to use, and very easy to remove if need be. There are others as well, but I always encourage artists to test any varnish they intend on using so that they can understand how it is applied, how it will look when dry, and how to use it based on their work because every painting is unique and what may work for one artist may not for another.

If you could give advice to the Old Masters about their work, what would you say?

You guys knocked it out of the park, what else can I say …

Related posts: