Erica Lome, Ph.D.

“Necessity is the mother of invention.” This adage certainly applied to many of the domestic objects produced in the nineteenth century that served as creative solutions to everyday problems; and for some women, one of those problems happened to be their husbands’ hair.

Avoiding Disaster

In 1783, a London barber named Alexander Rowland produced a new conditioner to groom, style, and promote the growth of hair. Made with a mixture of coconut or palm oil and other fragrant oils, the newly patented Rowland’s Macassar Oil became a hugely popular and nationally advertised product.

Having oiled and slick hair was soon the fashion for men (and women) of all ages and backgrounds, a trend that continued into the Victorian era. Unfortunately, the pungent and viscous oil tended to transfer from the back of one’s head onto the upholstery of a chair or sofa and leave behind a stain. By the 1850s, housewives had a solution: a piece of cloth, easily washable, which they placed over the back of the chair. Aptly, these fabric coverings came to be called antimacassars.

From Necessity to Craft

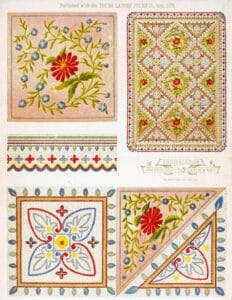

Antimacassars were a staple of the Victorian home. They were typically made by crocheting or tatting (creating a series of knots and loops) patterns into a durable fabric that could be washed and reused. And while the standard color was white, so as not to clash with the color of the upholstery underneath, pattern sources suggested they could be made from the odds and ends in different colors.

The intrepid needleworker might produce an original design or work from a sourcebook such as The Lady’s Every-Day Book: A Practical Guide in the Elegant Arts and Daily Difficulties of Domestic Life (1880) and turn to lacemakers for ideas using the latest fashion. These mundane objects reflected their owner’s tastes and contained subtle details that make them unique. The level of complexity varied, and displaying beautiful, hand-made antimacassars in the public space of the parlor signified not only a woman’s skill but her abilities as a homemaker.

An Art for Every Homemaker

Antimacassars were typically found in middle-class households, though mass-produced versions were available for any who desired to keep their upholstery unsoiled. As with other kinds of “fancy” domestic needlework, such as pillow covers or table runners, these objects were made to embellish the surfaces of a well-furnished parlor, and became canvases upon which a woman could express their creativity through elaborate patterns and complex techniques.

Most of the surviving antimacassars are from the early twentieth century. One particularly sophisticated example was made of linen and demonstrated a variety of techniques, including needlework on knotted net, bobbin, and needle lace. The design contains a heraldic device of a fleur-de-lis, shield, and flowering tree set into a large diamond surmounted by a series of woven panels. The make also included tassels at the pointed ends. This antimacassar was not meant to be soiled by hair oil and was more of a decorative statement.

By the 1920s and 30s, antimacassars belonged with crocheted doilies, tea covers, ornamental lacework mats, and other decorative covers whose “fussy” appearance in the home was considered a holdover from the Victorian era. Nonetheless, they were a failsafe domestic occupation for women concerned over having idle hands.

Designing Popularity

Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences.

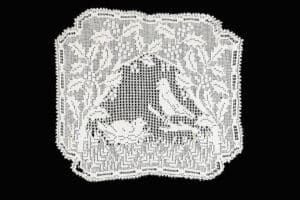

Antimacassars remained fashionable thanks to Mary Card, an Australian designer who published widely and was featured in the leading women’s magazines. While earlier antimacassars typically contained geometric patterns, Card popularized the depiction of flora and fauna in needlework designs. One such pattern featured a pair of birds perched on tree branches, surrounded by foliate and berries. A pair of matching armchair covers each contained a single bird in the same pattern. Made from ecru linen, the “filet” crocheted technique was intended to emulate fine lacework but has larger stitches and has a chunkier look.

A finer example was worked by a member of the Tucker family between 1900-1930. Inside Castle Tucker, their estate in Wiscasset, Maine, a beautiful antimacassar set in the parlor featured scalloped side and back edges, foliate decoration, and a peacock and swan. As with other early twentieth century antimacassars, this delicate lacework was meant to be admired but not touched, as etiquette dictated that the sitter does not lean all the way back on the sofa or chair.

Antimacassars were also used in public transportation. Trains, buses, and aircrafts placed fabric coverings on the seat headrests to extend the life of the upholstery and provide the appearance of sanitation. Linen companies produced these products in bulk, typically adorning plain beige linen with a decorative edging of machine-made cotton lace. In the case of the Pennsylvania Railroad, their antimacassars contained a stitched landscape image with their trademark locomotives. These commercial antimacassars remained in use for far longer than their domestic counterparts, which faded out of popularity in the postwar era. These days, you’re still likely to encounter plain antimacassars branded with a company logo, but those are a far cry from the lovely and unique objects produced by industrious homemakers over a century ago.

Erica Lome is the Peggy N. Gerry Curatorial Associate at the Concord Museum. She received her Ph.D. in History and Material Culture from the University of Delaware.

![Advertisement, Thomas Rowlandson, Etching colored, 1814. “Macassar Oil, for the Growth of Hair, is the finest invention ever known for encreasing [sic] hair on bald Places. Its virtues are pre-eminent for improving and beautifying the Hair of Ladies and Gentlemen. This invaluable Oil recommended on the basis of truth and experience is sold at One Guinea Pr [sic] Bottle by all the Perfumers and Medicine Vendors in the Kingdom.” “Wonderful Discovery, Carrotty or Grey Wiskers, Changed to Black Brown or Blue” “MACASSAR OIL, An Oily Puff for Soft Heads.”](https://journalofantiques.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Macassar-ad-740x1024.jpg)

Advertisement, Thomas Rowlandson, Etching colored, 1814.

“Macassar Oil, for the Growth of Hair, is the finest invention ever known for encreasing [sic] hair on bald Places. Its virtues are pre-eminent for improving and beautifying the Hair of Ladies and Gentlemen. This invaluable Oil recommended on the basis of truth and experience is sold at One Guinea Pr [sic] Bottle by all the Perfumers and Medicine Vendors in the Kingdom.”

“Wonderful Discovery, Carrotty or Grey Wiskers, Changed to Black Brown or Blue”

“MACASSAR OIL, An Oily Puff for Soft Heads.”

Related posts: