By Linda Eaton

John L. & Marjorie P. McGraw Director of Collections and the Senior Curator of Textiles at Winterthur Museum

Until relatively recently, scholarship on women’s needlework has focused on the 17th, 18th, and early 19th centuries. Susan Burrows Swan, whose book, Plain & Fancy, was first published in 1977 and reissued in 1995, and Betty Ring’s decades of research for Girlhood Embroidery, published in 1993, were among the many books and articles that have been influential.

More recently Paula Bradstreet Richter in Painted with Thread and Beverly Gordon’s article, “Spinning Wheels, Samplers and the Modern Priscilla: The Images and Paradoxes of Colonial Revival Needlework” in Winterthur Portfolio began to examine 20th century embroidery. Cynthia Fowler has looked at embroidery as an early 20th century art form in her recent book The Modern Embroidery Movement.

To millions of Mid-century and contemporary needleworkers, Erica Wilson has been dubbed America’s First Lady of stitchery. Through her devotion to the craft, Erica found fame as an educator, lecturer, needlework designer, and television celebrity across the country and around the world.

This is her story.

The Beginnings

Erica Wilson (1928-2011) trained at the Royal School of Needlework (RSN) in the late 1940s when it was based in a grand house in Prince’s Gate (across the road from Hyde Park) in London. Founded in 1872 by Lady Victoria Welby, its stated purpose was to revive the practice of high-quality embroidery and to provide employment to well-educated but impoverished gentlewomen. In 1876, the RSN exhibited their work, designed by artists like Walter Crane, at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia where it was a revelation to many people, including Candace Wheeler who later would write one of the first books on embroidery in America. From then on, the work of the RSN greatly influenced American embroidery, and many of their graduates, like Erica, came to North America to teach and still do so today.

After graduating from the RSN Erica taught individual classes there as well as in her mother’s home and sometimes in the homes of her students. Erica was invited to come to the United States in 1954 by Margaret Parshall (Mrs. Daryl) to teach at her embroidery school in Millbrook, New York, just north of New York City. Erica remembered that the first class she taught was on goldwork, a sophisticated and exacting technique. As many of her students claimed to be sick at the time of her second class, Erica soon changed her focus to crewel- work, which then proved to be much more popular.

Erica met her future husband, the award-winning furniture designer Vladimir Kagan (1927-2016) at a costume party at the Architectural League in New York – she was dressed as a poodle. Vladi (as he was known) was an integral part of Erica’s business. In addition to Millbrook, Erica also taught in the homes of some of her wealthy students and later in her apartment on Park Avenue or in a room at her husband’s manufactory on East End Avenue and later on 59th Street. She also taught at the Cooper Union, now the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum. She loved to teach and would regret that as her business became more successful she no longer had the time. Her long-term friend and employee, Edith (Edie) Lynch (later Bouriez), an accomplished stitcher, took over much of her teaching and other aspects of the business.

Establishing Her Brand

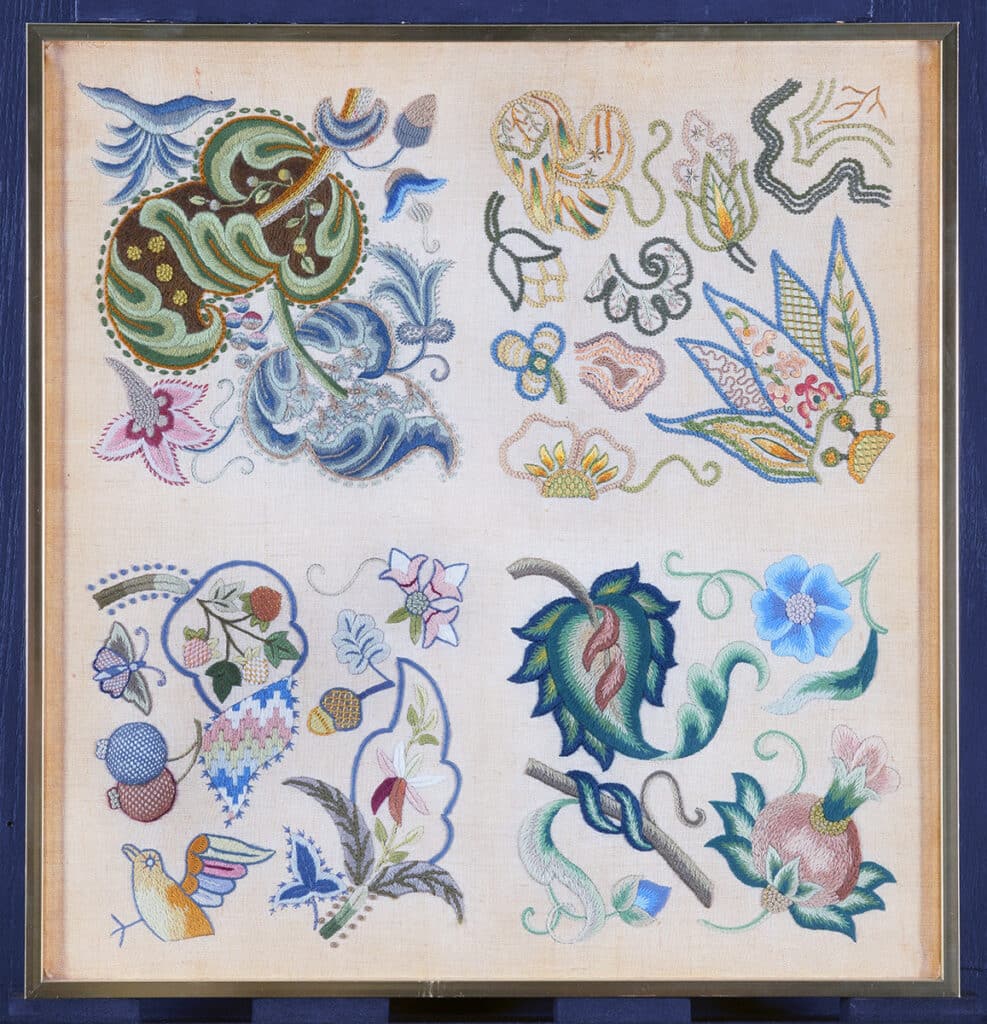

2015.0047.013 A, Gift of The Family of Erica Wilson, Courtesy of Winterthur Museum

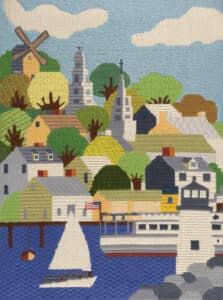

It was Edie and one of Erica’s students from Rye, New York, Mary Anne Beinecke, who suggested that Erica teach embroidery on Nantucket, where many of her students spent the summers. She and Vladi first rented and then purchased a house on Liberty Street, where she sold embroidery materials before opening a store in town. Lectures and demonstrations were held at Erica’s in the mornings, and the group would divide in two for afternoons of stitching in Erica’s and Edie’s backyards.

Erica and Vladi created what would later be called a lifestyle brand and her business was multi-faceted. She designed and fabricated kits and distance learning courses, wrote 21 books, created a television show on WGBH in Boston (where her studio was next door to Julia Child’s), designed and published for women’s magazines, organized international embroidery tours and cruises, undertook many public appearances, and operated another shop on Madison Avenue. Her most lucrative business venture was her contract with Columbia Minerva, signed in 1962 for the then astonishing sum of $100,000. Embroidery was a big business and was very popular throughout the 20th century. In the 1960s and 1970s embroidery materials and kits were sold on the ground floor of many high-end department stores, where cosmetics are sold today. Erica’s newsletter, The Creative Needle, had a readership of 300,000.

Designs of the Times

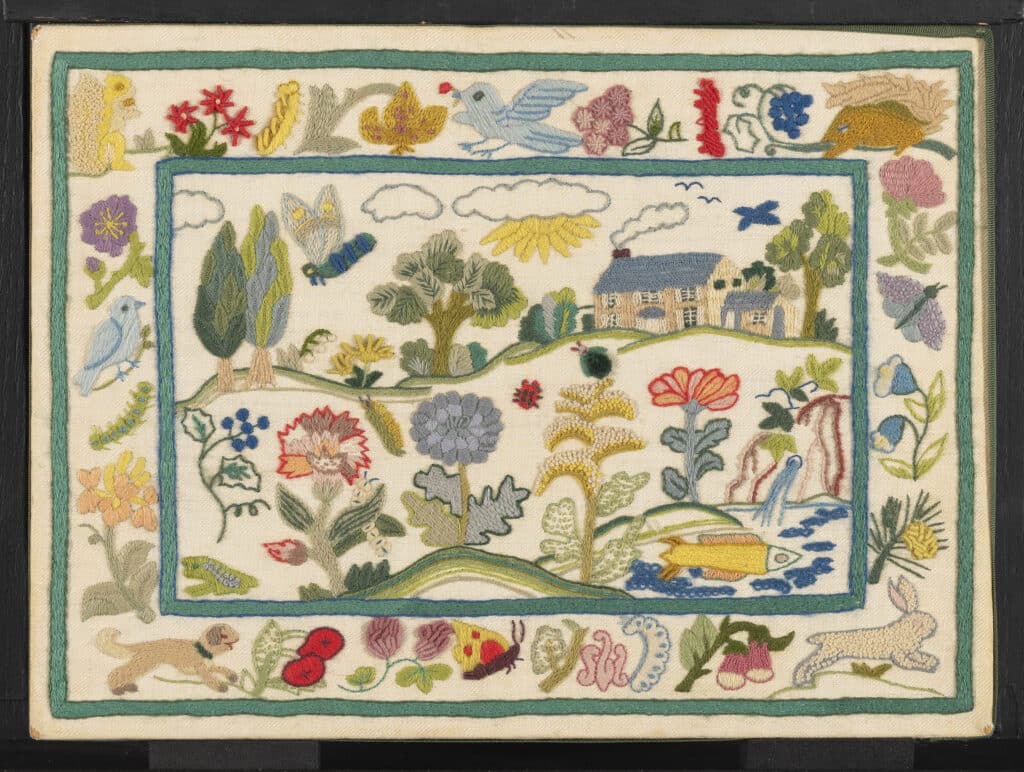

Erica’s designs often referenced historic prototypes but with a contemporary aesthetic, like her adaptation of a painting by Edward Hicks or her embroidered illustrations adapted from children’s books by authors such as Beatrix Potter and Edward Lear. She also created designs for upholstered chairs, clothing, and, in the 1990s, versions of the Unicorn tapestries at the Met, making them available as kits. Her influences were international; she adapted designs from Chinese and Indian embroidered clothing that she acquired on her tours and featured in her television shows, which are available to watch on WGBH’s Open Vault. Erica particularly enjoyed designing special commissions for private clients. One of her earliest was for Eleanor Roosevelt Jr., a school friend of Ruth Wales du Pont (wife of Henry Francis du Pont, Winterthur’s founder) and a noted embroiderer whose work is in the collection of the Smithsonian. Her last was for the comedian Joan Rivers. Erica’s sense of color was outstanding and widely admired.

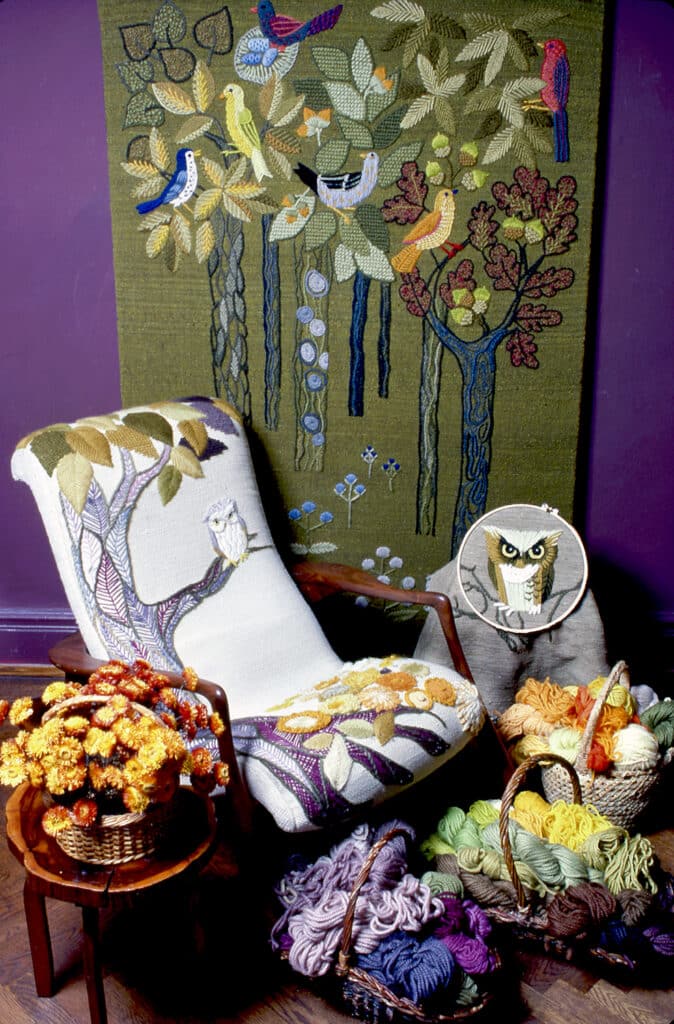

Everyone who knew her says that Erica was always working. She had no sense of time and was often notoriously late. Erica loved owls, perhaps because she was a night owl herself, often working into the early hours of the morning on the floor of her dining room. Erica was interested in teaching a wide variety of techniques using an array of many beautiful colored yarns, but she was under increasing pressure from Columbia Minerva to keep the cost of her kits down by using less expensive yarns, cheaper ground fabrics, and fewer colors. Throughout her career, Erica continued to produce designs and kits of her own using higher quality materials, but it was her Columbia Minerva kits that reached a mass market in department stores and needlework shops around the country.

A Legacy of Finding Joy

Erica’s public persona was friendly, engaging, and informal. Although her training at the RSN stressed a uniform technique, because many people worked on their large commissions where consistency was important, Erica was more interested in getting people to enjoy embroidery and not fuss about messy threads or knots on the back. She was supportive and encouraging both in her personal teaching and on her television show.

While Erica focused on design, Vladi spearheaded the financial side of her business, as well as running his own business. His furniture had been hugely popular in the middle of the century, but it was Erica who was the main breadwinner in the 1970s and 1980s. Then when Erica’s business was shrinking in the early 2000s, Vladi’s mid-century modern designs once again became fashionable, winning him many international awards for his work. Vladi later regretted not undertaking more joint projects with Erica. The rocking chair, designed by Vladi with upholstered needlework by Erica, appeared in many magazine articles featuring the couple and was displayed in the shop on Madison Avenue and later in their Park Avenue apartment.

When Erica Wilson died in 2011, her shop on Madison Avenue had closed, but the shop on Nantucket, operated by her daughter Vanessa, continues (ericawilson.com). In 2015 the family of Erica Wilson, one of the most successful needlework entrepreneurs of the second half of the century, generously donated examples of her work to Winterthur Museum and lent additional material for a book and an online exhibition, Erica Wilson: A Life in Stitches. Due to the coronavirus, Erica: A Life in Stitches will be an online exhibition only. A book with the same title by Anne Hilker and Linda Eaton will be available in the fall. Go to the Winterthur Store online or order a copy this fall.

Linda Eaton is the John L. & Marjorie P. McGraw Director of Collections and the Senior Curator of Textiles at Winterthur Museum. She has curated exhibitions on fakes and forgeries, quilts, and embroidery and is the author of Quilts in a Material World: Selections from Winterthur’s Collection and Printed Textiles: British and American Cottons and Linens 1700-1850.

Related posts: