By Maxine Carter-Lome, publisher

“Accentuate the positive and camouflage the rest,”

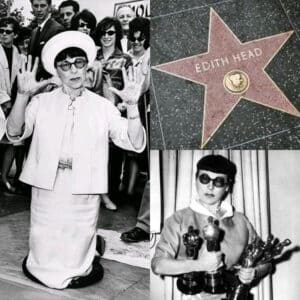

At barely five feet tall, Hollywood Costume Designer Edith Head (October 28, 1897 – October 24, 1981) was a giant in her field. She was also a recognizable personality in her own right thanks to her distinctive look of severe bangs, signature round dark glasses, and two-piece suits. In fact, Head’s personal style was so memorable and quirky that she was used as the inspiration for the Disney cartoon character Edna Mode, the costume designer in The Incredibles.

For over a half-century, from the 1930s to the 1970s, Head’s designs defined and influenced American fashion as seen in the movies, and was known to have dressed virtually every top female star in Hollywood. She is credited with crafting wardrobes for such stars as Grace Kelly, Tippi Hedren, Bette Davis, and Elizabeth Taylor, and for designing Audrey Hepburn’s iconic look in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, along with dress designer Hubert de Givenchy. Her work, however, was not limited to just women. Head also designed wardrobes for such dashing leading men as Cary Grant, Paul Newman, and Steve McQueen, to name a few.

Whether designing for black-and-white or color, Head was known for using a rainbow of hues to set the mood. When Technicolor emerged, Head dressed Ginger Rogers in a dazzling ruby gown for Lady in the Dark and outfitted Rosemary Clooney in bold turquoise for White Christmas. Surprisingly, Head only liked to wear four colors herself: black, white, beige, and brown.

Today, Edith Head is considered one of the greatest and most influential costume designers in film history, her work is instantly recognized for its association with some of the greatest movies of the mid-20th century.

Stitching Together a Hollywood Career

Edith Claire Posener was born in San Bernardino, California, in 1897 and raised in the mining town of Searchlight, Nevada. Edith Head was as American as the Hollywood films she worked on. She once said of her childhood, “I didn’t have what you would call an artistic or cultural background. We lived in the desert and we had burros and jackrabbits and things like that.”

In 1919, Edith received a Bachelor of Arts degree in letters and sciences with honors in French from the University of California, Berkeley, and in 1920 earned a Master of Arts degree in romance languages from Stanford University. She started her career teaching French and Spanish at private schools but quickly became bored, wanting to teach art instead, despite not having formal training. To improve her rudimentary drawing skills, Head began taking evening classes at the Otis Art Institute and Chouinard Art College in Los Angeles.

According to her 1981 obituary in The New York Times, Head answered a want ad for a sketch artist at Paramount in 1923. “In a telling example of the ambition for which she was known, Miss Head took to the interview a portfolio of work that was not hers but which she had borrowed from fellow students in a drawing class. Even though Howard Greer, then chief designer at Paramount, discovered the ruse, he hired her anyway and Miss Head’s career began.”

That same year, 1923, Edith Posener married Charles Head, the brother of one of her Chouinard classmates, Betty Head. Although the marriage ended in divorce in 1938 after several years of separation, she continued to be known professionally as Edith Head until her death. In 1940 she married award-winning art director Wiard Ihnen, a marriage which lasted until his death in 1979.

Over the next decade, Head toiled away on the back lots of Paramount honing her craft under her various mentors, Howard Greer, and his successor, Travis Banton, but it was her design of Dorothy Lamour’s trademark sarong in the 1936 film The Jungle Princess, that captured Hollywood’s attention and sparked a national fashion trend. That sarong also put Head on the fast track at Paramount.

In 1938, Head was named the chief costume designer at Paramount, the first woman to head a design department at a major studio, where she oversaw a costume department with a staff of hundreds. It is said Head managed to survive more through her ability to please quixotic directors and stars than for her design creativity, a distinction that even she acknowledged. She referred to it as “temperament.” “You have to have the patience of Job,” she once said about her job. ‘‘That’s why I’ve been around so long.’’ If her mentors taught her anything, it was how crucial it was to establish a rapport between the star and the designer.

Over the years, she worked her magic on such stars as Clara Bow, Mae West, Joan Crawford, Barbara Stanwyck, Ann Sheridan, Veronica Lake, Olivia de Haviland, Marlene Dietrich, Grace Kelly, and Elizabeth Taylor. She had a keen knack for visually transforming these actresses into whatever screen guise was required, whether in a period drama such as The Heiress, for which she won her first Academy Award, or an adventure film such as To Catch a Thief. “There isn’t anyone I can’t make over,” she pronounced. And her loyal clientele also knew, as Lucille Ball once put it, that “Edith doesn’t tell.” Of the times Head wrote, “Then, a designer was as important as a star. Dress was part of the selling of a picture.”

Head worked at Paramount for 44 years. In 1967, the new parent company of Paramount declined to renew her contract and she was invited by Alfred Hitchcock to join Universal Pictures, where she continued adding to her illustrious career resume. She remained at Universal until her death in 1981 despite working on outside projects.

And the Oscar goes to…

In 1948, when the Academy introduced an Award for Best Costume Design, Head became famous worldwide, going on to dominate the category in the coming decades of her career with a record eight Academy Awards for Best Costume Design and 35 nominations, making her the most awarded woman in the Academy’s history. Head was extremely proud of these recognitions and was known to refer to her eight Oscars as “my children.”

Head received her first Academy Award in 1949 for The Heiress, which was followed with awards for films that have become a part of Hollywood legend, including Samson and Delilah, All About Eve, A Place in the Sun, Roman Holiday, Sabrina, and The Facts of Life.

After leaving Paramount, Head earned her eighth and final Academy Award while at Universal for her work on The Sting in 1973. Of the award for The Sting, Head, who is said to have preferred designing for men, remarked with some pride, ‘‘It was the first time that the costume design Oscar went to a picture with no female star.’’

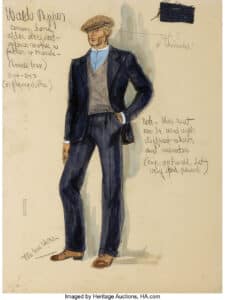

margins. The aviator sketch retains an Edith Head memo suggesting changes

to the jacket tipped to the lower right corner of the board. This drawing sold for $3,900 at Heritage auctions in June 2017.

While Head’s designs dominated Hollywood for over a half-century, she remembers the thirties as her favorite decade in Hollywood, when “the star was a star … [and] she wore real fur, real jewels.” Her job was to create fantasy, “to change people into something they weren’t – it was a cross between camouflage and magic.” Matinee audiences during the Depression and World War II were full of women who stood in line to see the latest fashions of their screen idols: “Then, a designer was as important as a star,” Head recalled. “Dress was part of the selling of a picture.”

Beyond Hollywood

Although Head is best known for her work as a Hollywood costume designer, her designs and style advice were in demand outside the Hollywood bubble, as well.

Head built on her Hollywood celebrity to purvey her ideas about practical and simple design through a network of other commercial channels. She wrote articles for Photoplay magazine about how the average girl could dress like a star, licensed her name for Vogue pattern designs, and, beginning in 1948, appeared as a regular guest on Art Linkletter’s House Party, where she gave women in the audience practical advice about how to dress and generally improve their looks.

She also authored two books describing her career and design philosophy, The Dress Doctor (1959) and How To Dress For Success (1967). These books were re-edited in 2008 and 2011, respectively.

A third book was published posthumously in 1983 by E. P. Dutton, Inc., co-written by Edith Head and Paddy Calistro, and featuring a forward by Bette Davis called Edith Head’s Hollywood describes some of the hundreds of productions she worked on and gives her personal impressions of the actors and actresses for whom she created costumes. A 25th Anniversary Edition came out in 2008. The book features 96 pages of black and white photos among its 296 pages.

Head was also known for creating airline uniforms for Pan Am from 1975-1980. Her iconic pantsuit uniform, complete with an infinity blouse and hat, offered two color palettes: navy blue or “Pan Am Blue.” These uniforms were in service until 1980.

In the late 1970s, Edith Head was asked to design a woman’s uniform for the United States Coast Guard because of the increasing number of women enlisting. Head called the assignment a highlight in her career and received the Meritorious Public Service Award for her efforts.

The Value of Sketches

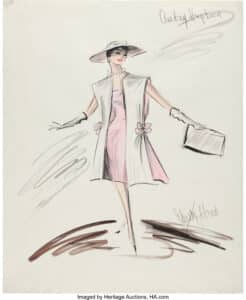

Audrey Hepburn “Jo Stockton” Costume Sketch by Edith Head for Funny Face (Paramount, 1957). Vintage original costume sketch accomplished in gouache and ink on 14” x 16.75” artist’s paper leaf by legendary costume designer Edith Head. Designed for fashion icon Hepburn, there were multiple variations worn by six actresses during the fabulous “Think Pink” segment. Edith was again nominated for the “Best Costume Design” Oscar. This sketch sold for $6,250 at Heritage Auctions in July 2022.

At auction, Head sketches remain widely popular and highly collectible. They are also only accelerating in price as the years go on, with marquee names for memorable films commanding the highest values. Here are the results from a few 2022 auctions:

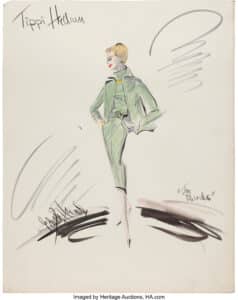

A vintage original costume sketch by Edith Head for Tippi Hedren as “Melanie Daniels” in The Birds (Universal, 1963) sold for $11,875 this past July at Heritage Auctions. Also at that auction, an Audrey Hepburn “Holly Golightly” costume sketch by Head for Breakfast at Tiffany’s (Paramount, 1961) sold for $38,750.

A pair of gouache and ink on paper original costume sketches from the production of The Lucille Ball Comedy Hour: Mr. and Mrs. (Desilu Studios, 1964) by Edith Head, with each sketch signed to the bottom right by Head, sold for $3,840 at Julien’s Auctions this past December.

A Head sketch of an original costume design for Judy Garland in the film I Could Go On Singing, 1963, inscribed by Head in pencil “Garland” at the upper right and signed “Edith Head” at lower left, sold for $22,000 at Helicline Fine Art in New York City.

Edith Head claimed to have designed 1,131 films throughout her career. Her drawings captured the essence of the actor in a particular role and were drawn with a flair for movement and personality. Over the years, film and fashion fans have developed an appreciation for the woman whose story is as fascinating as the history of the film industry itself, for she helped shape the Hollywood we know today.

To learn more about Edith Head and her incredible designs, check out these videos available to view at our Video Gallery

Related posts: