By Bob Frishman

This article was first published in the NAWCC journal. This abbreviated version of the original article has been reprinted with permission from its author, Bob Frishman. To view and read the entire version, please click here.

Since the 13th-century invention of mechanical timekeeping, clocks and watches have appeared in art, but never by accident or unintentionally. Even before the invention existed, artists’ depictions of water clocks, sundials, and sandglasses also represented fleeting time, human mortality, technological sophistication, owner affluence, self-discipline, or even just the time of day.

Nearly 20 years ago, I began noticing horology in fine art from the past. A 1590 portrait by Annibale Carracci portrays a dark-skinned woman in servant’s attire holding a small, ornate gilt-brass table clock. An 1812 Jacques-Louis David late-night portrait of Emperor Napoleon, now at Washington, D.C.’s National Gallery of Art, includes an elegant regulator standing with its visible high-precision gridiron pendulum. The surprisingly small painting of Salvador Dalí’s melting clocks attracts crowds of viewers at The Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

American Folk Art Horology

Clocks and watches do appear in American folk art often prominently, reinforcing a narrative or serving as familiar symbols and metaphors. In those paintings, timepieces stand in corners, perch on mantels, hang on walls, dangle from chains and fingers, and peek from pockets.

When they were made affordable, clocks and watches were highly important possessions for Americans in the 18th and 19th centuries. Probate inventories demonstrate that timepieces were among the most valuable household items. In American folk art, a watch or clock spoke loudly to early viewers, as they still can today. I own a few original examples, better than computer-screen images or printed pages and museum galleries. A recent acquisition (Figure 1) is a circa 1840 miniature-on-ivory attributed by Philadelphia dealer Elle Shushan to Samuel P. Howes (1806–81).

As in similar full-size folk-art portraits, Howes’s miniature shows a pocket watch in a small front dress pocket, secured to a very long gold chain draped around the sitter’s shoulders and curling below her pocket. Half of the case is visible, whereas other images often reveal only the top bow, just hinting at a watch below.

A circa 1840 portrait (Figure 2) could be mistaken for one of those larger American portraits, but instead, I viewed it in January 2020 at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery in Hobart, Australia. The artist was William Buelow Gould (1801–53) who produced an artwork amazingly similar to many painted here. He was born in Liverpool and in 1827 was transported as a seven-year convict to Tasmania for having by “force of arms stolen one coat.” He never returned to England or set foot in America. The watch of Eliza Biggs is tucked inside her broad belt of the same green color as her fashionable dress. The looping black watch ribbon echoes the lace halo framing her face.

Questions may arise about whether a shiny case was a watch or a locket. However, before the introduction of inexpensive photographic portraiture in the mid-19th century, round watch-form lockets were uncommon ways of keeping a loved one’s visage close to the heart. Miniature-painted portraits were more likely to be oval and open-faced, while images inside covered lockets became widespread only later in the Victorian era. In folk-art portraits where the object is fully out of the pocket, it is a watch.

Artwork with a Remembrance

A second original artwork of mine was for sale in a booth adjacent to mine at an antique show. (Figure 3) Written in pencil on the gilt frame’s wooden backboard is the notation, “Drawn by Chas. Rundlett of Ports. NH.” A yellowed, stained paper is also affixed to the back, on which is penciled, “This was drawn by Chas. Rundlett of Portsmouth NH from the enclosed card.”

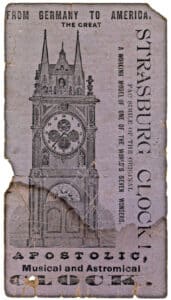

The “card,” (Figure 4) also attached to the backboard, is a purple-toned illustrated ticket announcing in various type fonts and sizes, “From Germany to America the Great Strasburg Clock Fac Simile of the Original, A Working Model of One of the World’s Seven Wonders, Apostolic Musical and Astronomical Clock.” Mr. Rundlett is otherwise unknown, but his rendition of the clock is skillfully executed.

Perhaps Charles Rundlett traveled the 60 miles to Boston and was inspired after viewing the clock, as shown in contemporary photos, looming about 10’ tall in front of a backdrop of boldly printed drapery. The real Strasburg clock, one of the world’s largest, rises nearly 60’ tall in the Cathédrale Notre-Dame. With its multiple dials and automata, it is now known as the “Strasbourg” clock since the city is French again. In the spring of 2019, I traveled to the Cathedral only to find the clock fully covered by a painted shroud to conceal major restoration work.

Time Makes Its Mark

I travel only two miles from my home to appreciate a lovely miniature owned by the Andover Center for History & Culture (Figure 5). In early 2017, the Center mounted a Back in Time exhibit of its horological holdings where I peered with joy at this mother-and-child painting in a gilt frame. The artist was town native Clarissa Peters Russell (1809–54), an important American folk-art miniaturist also known as Mrs. Moses B. Russell whose husband was a painter, too. Her many extant portraits of children suggest that these were her specialty. In this double portrait, the gold watch is out of the mother’s pocket and clutched by the child. If that grasp weakened, the mother had hold of the long black ribbon, less costly than a gold chain. Because of the woman’s black dress, and the familiar symbolism of a watch representing mortality, there is the possibility that this work was painted posthumously.

The 2016–17 exhibit at the American Folk Art Museum, Securing the Shadow: Posthumous Portraiture in America, focused on this theme. The exhibit included a private-collection example of a boy holding a watch and chain, attributed to Aaron Dean Fletcher (1817–1902). The description, reproduced on page 113 of the exhibit catalog, states, “In this example, surmised to have been painted posthumously, the child no longer has time on his hands; instead, the watch is suspended from a chain with the winding key pointing heavenward—a sign that it will be wound no more.”

A Horologist, Painted

A portrait of an actual watchmaker (Figure 6) was purchased in Vermont and is in the collection of Old Sturbridge Village in Massachusetts. Neither the sitter nor the artist is known, but the ocean and hilly coastline viewed through the window makes the painting’s assumed inland origin somewhat questionable.

For horologists, the craftsman’s tools are interesting; they include a magnifying loupe and brass double-end calipers used for “truing” balance wheels. The watch proudly displayed by the watchmaker appears to be a typical English timepiece in a thick multipiece hinged, hallmarked silver case, popular and prevalent in America during the hundred years before the Civil War. Few watches at that time were made in America; our “watch makers” principally were repairers and sellers, as has been the case subsequently as well.

For the Children

Children are the sole subjects of some paintings. Sold at a 2013 Skinner auction, a painting by Erastus Salisbury Field, one of our best-known folk artists, featured a boy (Figure 7) living around 1850. Typically, just one of his ears is visible, but the large watch and its thick ribbon are front and center.

A little boy in 1830s attire was caught listening to a watch ticking. The description from the Minneapolis Museum of Art suggests that the portrait, attributed to Samuel Miller, is posthumous, not only because of the watch but also because of the pistol-form watch key. When touring the American Museum and Gardens in Bath, England, in 2019, I saw yet another portrait of a boy with a watch to his ear (Figure 8). It is dated circa 1835 with attribution to Dr. Samuel Addison Shute (1803–36) and/or Ruth Whittier Shute (1803–82).

A circa 1835 Joseph Davis painting of the Frost family is centered on a looking-glass clock, showcasing its bronze powder stenciling and floral-painted dial (Figure 9). This raises the subject of folk art on clock cases, dials, and glasses, a subject perhaps for a future treatise. Whether the Frosts owned such a clock is uncertain; the painter easily could have added signs of affluence, such as the fancy-painted furniture and floor cloth, which may not yet have been in the family’s inventory.

While less expensive than a tall clock, a decorative shelf clock still could cost as much as $10, more than nearly any other household item they owned. Rufus Porter, for example, would paint a mural covering an entire large room for less money.

From German-speaking Pennsylvania, several frakturs depict clocks with their traditional symbolism. One colorful example, with an abundance of fine script (Figure 10), sold in 2019 at Skinner. It was a circa 1840 pen-and-ink watercolor birth letter from Pennsylvania titled The Spiritual Chimes. Clocks from that time and place can be highly decorative, but usually not to such an exuberant extent.

Professor David P. Jaffee (1955-2017) read from his 2010 book A New Nation of Goods: The Material Culture of Early America at the 2015 Historic Deerfield Decorative Arts Forum. I appreciated his insights even more. Entirely relevant to timepieces in American folk art, he asserted that artifacts were not “tossed in just as illustrations” and that if we “learn to look” we can gain much knowledge about the lives and culture of our forbearers.

About the Author

Bob Frishman was introduced to horology in 1980 and in 1992 founded Bell-Time Clocks for repair and sales. Always more than a vocation, horology has important connections with history and culture that have drawn him to its broader significance. As a horology scholar and promoter, he has written more than 100 articles and reviews, lectured to public audiences more than 100 times, and organized related conferences at Winterthur, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Henry Ford Museum, and Museum of the American Revolution. He is a Fellow of the National Association of Watch & Clock Collectors, and a Liveryman of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, London, England. Presently he is researching and writing a book about Colonial Philadelphia clockmaker Edward Duffield. Learn more at www.bell-time.com.

Related posts: