By Sarah P. Turnbaugh

Photos by William A. Turnbaugh

As crisp cooler days and long evenings usher in autumn, our thoughts turn to cold-weather activities, collectibles, and art.

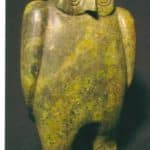

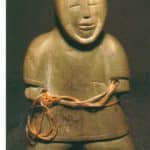

Stone sculptures of marine mammals or birds, parka-clad hunters, or similar carvings, occasionally show up in flea markets or group shops with no information attached. In addition to subject matter, a major clue to their origin lies in the color of the stone itself. It may range from black or gray, to greenish, bright apple green, or beige. If so, the figure is likely a product of Canada’s Arctic peoples.

Today, instead of “Eskimo,” these dwellers in the Canadian Far North prefer to be called “Inuit” (singular is “Inuk”), meaning “the people.” The native stone sculpture that has caught your eye may be a highly prized art object, or possibly just an inexpensive imitation. But how do you know?

Prehistoric Art

Native peoples have occupied the Canadian Far North for over 4,000 years. By about 3,000 years ago, Arctic inhabitants identified with the Dorset culture were carving bone, ivory, and wood into little human, animal, and bird forms. Their tiny three-dimensional figures likely served as protective amulets or were associated with shamans’ religious or magical rituals.

About 1,000 years ago, a different population — people associated with the Thule culture — migrated into northern Canada from northern Alaska, displacing the earlier Dorset population. Thule people are the ancestors of today’s Inuit, but Thule art differed from Inuit sculpture. The Thule decoratively engraved useful objects like harpoon toggles, buttons, and gaming pieces. Thule art was practical. It was neither purely artistic nor tinged with magical associations.

Explorers and whaling crews, fur traders, and Western missionaries established contact with the Inuit throughout the region by the 1500s. At the time, the Inuit were creating tiny carvings of humans and animals for their own use as toys. As European contact expanded, the Hudson Bay Company trading posts encouraged native carvers to offer some of these appealing little carvings as trade items. At this time, these tiny native stone carvings were seen as handicrafts and “souvenir” art and became popular as European contact expanded.

With more frequent, lengthier contact with non-Inuit whalers, traders, and missionaries by 1850, the Inuit found their native hunting lifestyle increasingly threatened. European and American whaling and fishing, harvesting of Arctic mammal furs and skins, and exploration for natural resources like oil and minerals stressed the native population. The Inuit had relied on bartering and a marginal hunting lifestyle, rather than on a westernized cash economy. Physical survival of traditional, nomadic Inuit families had been precarious, at best, from one year to the next. Inuit survival was just as tenuous in other ways as the native people, lacking a monetary economy, began to transition into settlements and westernized communities by the mid-1940s.

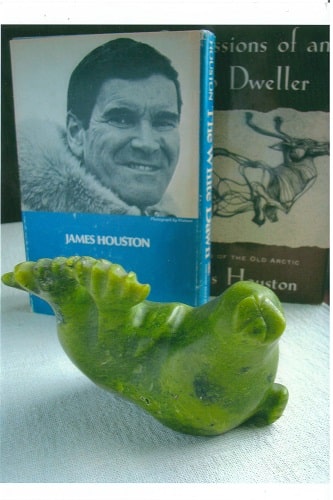

Following World War II, a talented and creative young Canadian artist, the late James Houston (1933-2009), traveled by dogsled through the Far North to sketch. He quickly recognized the plight of the Inuit and their growing problem. Houston began to advocate for the Inuit and engaged the Canadian government, the Hudson Bay Company, the Canadian Handicrafts Guild, plus a handful of patrons in supporting a new endeavor.

While seeking solutions, Houston and the Canadian government lit upon the potential economic benefit to the Inuit of encouraging their artistic abilities, first through stone sculptures and later through lithographic (stone-carved) prints. Together, their cooperative efforts soon elevated native handicrafts to fine art and created an economic base for the Inuit.

For more than a decade, Houston remained in the Far North, instructing and encouraging both men and women, and supplying the new market for Inuit art. Income from the carvings, along with the development of cooperatives and dedicated Government support, eased Inuit transition from family camps to small settlements. Integration to westernized lifeways increased through the 1950s and 1960s.

Today, over 30 Inuit communities across Arctic Canada are known for their distinct sculptural styles. Although most Inuit now live in small villages or communities, their earlier lives as igloo-dwelling hunters remain the most popular subjects for carvings. Realistic themes include the parka-clad Inuk hunter, mothers and children, and Arctic birds and mammals like seals, walruses, and bears. Spirit figures and transformational or mythological creatures are also popular. Hunters bearing rifles instead of harpoons and subjects like an Inuk holding a water-logged boot and suffering from frostbite or Arctic hysteria are less common. Many sculptures may be purchased at prices ranging from less than one hundred dollars to well into four figures.

Signatures and Authenticity

As with many popular art forms, “imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.” Inuit sculpture is no exception. Imitations in plastic or “cast-stone” circulate widely. They can be confused with the genuine, Canadian government-endorsed stone carvings, so look closely at each piece. Imitations usually are cast and are not hand carved or incised.

Knowledgeable dealers, galleries, and auction houses can confirm the authenticity of genuine Inuit sculpture. They can help verify the artist’s incised signature (often written in phonetic syllabics of their Inuktitut language). They also may help to identify the government registration or disc number that starts with an E or W and is sometimes found on the base of a genuine piece.

A trademarked “igloo” tag or similar sticker also may be present on authentic Inuit work. The “igloo” tag generally lists the artist’s name, village, year, and description of the work. The Canadian government has registered and trademarked the specific “igloo” tag/sticker illustrated in this article. Similar “igloo” variations are sometimes seen, as well, but these are NOT Canadian government-issued indicators of authenticity.

Further information on Inuit art as well as biographies of many native carvers appear on various internet websites, including katilvik.com and the Inuit Art Foundation (Inuit Artist Biography System) computer database for over 4,000 Inuit artists. Dedicated auctions of Inuit sculpture are held twice a year plus on-line at Waddington’s Auctions in Toronto: inuitart.waddingtons.ca and at Walker’s Auctions in Ottawa: walkersinuitart.com

Other auction houses and regional galleries throughout New England and Canada specialize in Inuit art and are listed on the web under “Inuit art for sale.” Several include Skinner Auction house in Marlboro and Boston, MA; and the galleries Home and Away Gallery, Kennebunkport, ME; and Inuit Images, Sandwich, MA. All have helpful and knowledgeable specialists.

Useful publications include “Inuit Art Quarterly,” the magazine of the Inuit Art Foundation; “Inuit Art: A History,” by Richard C. Crandall (2000, McFarland & Co.); “Sculpture/Inuit” (1971, University of Toronto Press/ Canadian Eskimo Arts Council); and the informative and engaging writings of James A. Houston.

The authors acknowledge and thank several anonymous private collectors for permitting photos for this article.

Related posts: