By Judy Gonyeau, managing editor

At 17, John took an apprenticeship with Captain Benjamin Lawrence, a local blacksmith, who did work for Middlebury College. While there, Deere gained a reputation for his skill, attention to detail, and ingenuity. According to the College’s Museum of Art, “He quickly became skilled in smithing ironwork for wagons, stagecoaches, and farm tools.” All of which would serve him well as he began working for himself.

After opening his own shop in Vergennes and then in Leicester, Deere gained a reputation for making well-crafted polished hay forks and shovels that drew farmers from throughout Western Vermont to his forge to make a purchase. By this time, he had married Demarius Lamb, a wealthy local girl, and together they raised 9 children.

Deere and his family moved throughout Vermont in search of steady work. In 1836, the New England economy collapsed, and Deere left Vermont to head west with other pioneers. After settling in Grand Detour, Illinois, he established another blacksmith shop and started working within a few short days of opening the business. He did work as a farrier, working with horses and oxen, and found a bounty of repair work on farm implements coming into the shop. The cast-iron plows brought west were designed for the lighter, rocky soil in the east, but did not work nearly as well in the “muck” found on the prairie in Illinois. Deere studied the reasons so many plows were coming in for repair, and in his desire to remedy the situation, he created an innovation that would secure his name in the pages of history.

The Steel Plow

As Deere grew his business thanks to the numerous repairs needed on the farmer’s cast-iron plows, he realized why these were not effective when battling the prairie fields. The land was made up of sticky soil and clay and would not “scour,” or pile up to the sides along the plow line as they did in New England. Farmers were having to clean the moldboards by hand every few feet to take off the clumps of dirt that became stuck to the plow. This was a problem just waiting to be solved by Deere, thanks to his early days in the family tailor shop.

As a seamstress, Deere’s mother was constantly sharpening and polishing her sewing needles in order to have them work with tougher textiles such as wool and heavy cotton. By doing so, the steel needles worked with less effort as the forthright and delicate series of stitches were created. Deere had discovered that polishing the tines of his popular hay forks and the blades on his shovels meant they went through crops and dirt easily and applied his knowledge to the blade of the plow.

Deere’s invention of his polished steel plow was not the first, as the overall design of the plow had been around for hundreds of years. It turns out that Thomas Jefferson created an iron moldboard plow designed to work through the soil with much less strain. Jefferson’s design, based on plows he observed while serving in Europe, was easily duplicated. Later, he began to cast them out of English steel. The fact that Jefferson’s design was not patented made it easily adopted by blacksmiths throughout the country. Deere’s original plow, designed in 1837, had a slightly “tinkered” plow shape that he made using a circular blade from a local lumber company that was rendered from fine English steel. Deere cut off the teeth of the blade and shaped it into a curving parallelogram that could pass through the soil more easily.

In early 1838, Deere completed his first steel plow and sold it to a neighbor named Lewis Crandall. News quickly spread about its effectiveness. The plow’s ability to break through the ground was not just the shape of the steel, but that “he polished his steel so smooth that the thick clay-like soil would slide right across the blade” that made the biggest difference in the ability of the plow to cut through the sticky soil. The highly polished steel would actually clean itself as it went through the soil, which scoured easily.

John Deere: Businessman & Marketer

In 1841, at a time when 90% of the population lived or worked on farms, Deere was producing 75-100 plows in a single year. To keep up with demand, Deere joined forces with Leonard Andrus in 1843 to be able to produce more plows. Because both men had a stubborn streak, the relationship was strained. Deere wanted to sell to people outside of the Grand Detour area as Andrus opposed the railroad coming to their part of the state. This along with other points of contention continued to break down the partnership. By 1848, Deere and Andrus had distanced themselves from one another and reached a breaking point. Deere was untrusting of Andrus’ accounting methods, and Andrus was sticking to his more localized approach to business, resulting in the dissolution of the partnership.

Looking for a more advantageous location, Deere and his family then moved to Moline, Illinois, a transportation hub along the Mississippi River. There, he was able to take advantage of waterpower and signed a contract with Pittsburgh Steel to keep up with increasing demand.

Once relocated to Moline, Deere formed a partnership with Robert Tate and John Gould and built a 1,440-square-foot factory that same year. Production rose quickly, and by 1849, the Deere, Tate & Gould Company was producing over 200 plows a month. A two-story addition to the plant was built, allowing further production.

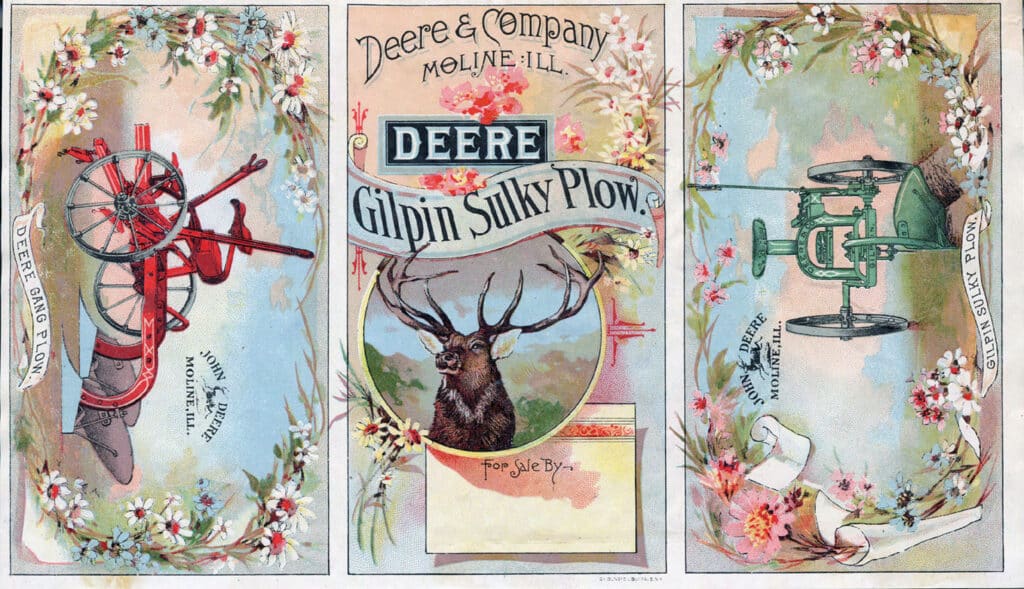

Charles Deere officially joined his father’s company in 1853 at the age of just 16. Though not considered to be the “heir apparent” since he was not the eldest, Charles’ strong work ethic from years of helping his father paid off. By the age of 21, he was handling the primary management of Deere & Company (incorporated in 1868) and continued to spearhead the company for 46 years. Under his leadership, the company expanded its production of steel plows, cultivators, and corn and cotton planters among other farm implements.

Dealer Mail Emblem, Cast Iron,16” tall x 8” wide, sold for $79.99 on eBay

Deere bought out Tate and Gould’s interests in the company in 1853 and was joined in the business by his son Charles Deere. By 1855, Deere’s factory was selling over 10,000 steel plows in one year. The plow’s nickname, “The Plow that Broke the Plains,” was put on a marker near his birthplace in Rutland, Vermont.

In 1858, a nationwide financial recession took its toll on the company. To prevent bankruptcy, the company reorganized, and Deere sold his interests in the business to his son-in-law, Christopher Webber, and his son, Charles Deere, who would take on most of his father’s managerial roles. John Deere served as president of the company until 1886.

The company was reorganized again in 1868 when it was incorporated as Deere & Company. While the company’s original stockholders were Charles Deere, Stephen Velie, George Vinton, and John Deere, Charles effectively ran the company. In 1869, Charles began to introduce marketing centers and independent retail dealers to advance the company’s sales nationwide. This same year, Deere & Company won “Best and Greatest Display of Plows in Variety” at the 17th Annual Illinois State Fair, for which it won $10 and a Silver Medal.

The Hawkeye Riding Cultivator and More

Not one to put all his eggs in one basket, Deere made a variety of farm implements (along with the occasional non-farm-related items) that formed the bedrock of his business’ success. Another important example is his manufacturing of the Hawkeye Riding Cultivator, the first piece of riding farm equipment, made starting in 1863.

Many of the men returning from the Civil War were wounded and unable to run the walk-behind tools on the farm. By improving upon an original patent by W. Furnas, Deere was able to alter the original so it could be ridden and use horse-power to pull the contraption, allowing men with injured or missing limbs to cultivate their fields.

In his promotional flyer, it reads “We have many testimonials from the best farmers in South-eastern Iowa, where it has been known since its invention, bearing us out in the statement that it is the most perfect working and easiest managed machine for cultivating corn that has ever been invented.”

Other early farm implements made by Deere included a variety of steel plows, cultivators, corn and cotton planters, harrows, wagons, and buggies. When the bicycle craze swept the country in 1894, Deere responded with a few different models of bikes. Once the craze calmed down, the production of bicycles ended.

The ability of Deere and his workers to respond quickly to the needs of consumers kept the business afloat in good times and bad. On another interesting note, the company enacted environmental controls in its manufacturing plants as early as 1903. This adherence to environmental principles carries through to decisions made regarding the company’s product line to this day.

John Deere: The Later Years

Deere focused on civil and national affairs later in life. He served as the president of the National Bank of Moline, director of the Moline Public Library, and he became Mayor of Moline but was unable to run for a second term due to health issues.

When Deere’s wife passed in 1865, he went on to marry her sister, Lucinda Lamb, in June 1867. Deere passed away at the age of 82 on May 17, 1886, at home with his wife by his side.

According to the blog edisonnation.com, in 2013, The Smithsonian Magazine selected John Deere’s plow as one of the “101 Objects that Made America.” The plow was chosen from 137 million artifacts held by the Smithsonian’s 19 museums and research centers to include on a list of items that changed the course of U.S. History. Deere’s ability to see a problem and make improvements to solve it is a driving force in the success of his namesake corporation to this day.

Related posts: