by Maxine Carter-Lome

Some product brands are such a part of our zeitgeist that their logo alone is enough for immediate recognition. Think Blue Ribbon and what beer comes to mind? Pabst, of course, the blue ribbon of beer, “Selected as America’s Best in 1893.”

Today, one of the oldest and most iconic of American beers, restyled “PBR” for the new millennium, is taking the hipster market by storm, spawning a new generation of fans, collectors, and collectibles. Its parent company, Pabst Brewing Company, has grown into the largest American-owned brewery in the country, with over 30 beer brands in its portfolio, including Lone Star Beer, Schlitz, Old Milwaukee, Schaefer, Blatz, and Colt 45. How this American-made beer, brand, and brewery has survived for over 170+ years, including through Prohibition, while remaining relevant, is a story with its roots in an immigrant family from Germany, a marketing-savvy steamboat captain, and the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893.

The history of the Pabst Brewing Company can be traced to 1842 when two brothers from Mettenheim, Germany—Jacob Best, Jr. and Charles Best—immigrated to Milwaukee, Wisconsin. There, they saw possibilities for themselves and their family’s future in what was then a fledgling frontier town. The brothers established themselves by setting up a small vinegar works and convinced their father Jacob Best, Sr., a brewer in Mettenheim, and two other brothers, Charles and Lorenzo, to join them. Two years later the family pooled their resources to open a small brewery on Chestnut Street named Empire Brewery (Est. 1844), and created a family business that supported their new life here in America.

Choosing Milwaukee as the new American location for their family business was a calculated move on the part of the Best family. It was ideally located on Lake Michigan with access to the ice necessary for beer production, particularly German-style lager beer. The surrounding farmland was perfect for grain production. Also, tracks were being laid for an inter- and intra-state rail system that could cost-effectively bring their goods to an expanding market.

The rapid influx of Germans into the region by mid-century guaranteed a supply of both workers and consumers for Best’s beer. By 1850, Germans represented 40 percent of Milwaukee’s population, making it the city’s largest ethnic group.

Empire Brewery was what could be described today as a micro-brewery, producing only about 300 barrels a year in its early years. Perhaps that made the business too small for such a large family. In 1850, Best Sr.’s sons, Charles and Lorenz, left the family business to start their own company, Plank Road Brewery. This eventually became the Miller Brewing Company when it was purchased in 1885 by fellow-Milwaukeean and German, Frederick Miller, for $2,300.

In 1853, Jacob Sr. retired leaving his sons Phillip and Jacob Jr. to continue operations as a partnership, with Phillip at the helm. In 1860 when Phillip took full control of the company he renamed it Phillip Best & Co. An infusion of cash from his new son-in-law and newly-named vice president, Frederick Pabst, positioned the company to acquire Melms Brewery and, combined with Frederick Pabst’s marketing instincts, put the company on the road to exponential growth. By 1874 Phillip Best Brewing Co. was the nation’s largest brewer.

The Company’s Namesake

Frederick Pabst came to America from Germany with his family in 1848. Settling first in Milwaukee, the family soon moved to Chicago. As a young man, Pabst worked as a waiter before becoming a cabin boy for the Goodrich Line, a steamship company that operated on Lake Michigan. For eight years Pabst sailed the lake and studied navigation, and by 1857 he had become captain of the Goodrich steamer Huron. As captain of the Huron, Pabst met the woman who would change his life: Maria Best, Phillip Best’s daughter. The couple married in 1862.

As fate would have it, in December 1863, Pabst’s ship Sea Bird was beached by a storm at Whitefish Bay, north of Milwaukee. Shaken by the incident, Frederick decided to join his father-in-law in the brewing business despite having no brewing background. He did, however, come to the partnership with capital, using his insurance proceeds to purchase a 50 percent interest in the company.

By the turn of the century, the German-born Pabst was one of the most successful brewers in the United States, one of the largest property owners in Milwaukee, and a leading community figure.

Captain Pabst died in 1903, leaving his children and his eldest granddaughter one million dollars in company stock (over $30 million in current dollars). His sons Gustav and Fred Jr.—both educated at military academies and trained as brewers at Arnold Schwarz’s United States Brewers’ Academy in New York—were put in charge of the business as president and vice president, respectively. His boys were more than well prepared for what was to be the family’s next challenge – surviving Prohibition. The goal was to preserve the brand, company, and their blue ribbon beer for future generations.

How Pabst Got Its Blue Ribbon

According to brand lore, Pabst got its famous “blue ribbon” after its Best Select beer won a competition at the World’s Fair of 1893. Breweriana historians now tell a different story.

The World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893 (also known as the Chicago World’s Fair) put Chicago and the American Midwest on the map as a hub of international trade and commerce. Forty-six nations participated, and over the six months of the Fair, 27 million people visited — half the U.S. population at the time. While transportation and architectural innovations were in no short supply, the world’s fair also exhibited for the first time: cutting-edge clothing (the zipper); food (Juicy Fruit gum, Crackerjacks, Shredded Wheat); and beverage products – including beer. Many exhibitors entered competitions to gain attention for their brands. Brewers like Anheuser-Busch and Pabst competed for “best beer,” with Pabst declaring its beer the “blue ribbon” winner; however, research shows that the scoring of the contest and the outcome wasn’t so clear.

Pabst was invested in the promise of the World’s Fair to raise the visibility of his company and its Best Select beer. The company hired Milwaukee architect Otto Strack to design a trade pavilion in the Fair’s Agricultural Building to display its product and dazzle its guests. Strack erected a thirteen square foot model of the Pabst Brewing Company’s building atop an elaborate platform supported by gnomes within the pavilion’s interior. It was reported at the time that “the model, washed in gold, is said to have cost Captain Pabst $100,000 and was highly regarded at the fair for its beauty of presentation.” The entire structure was constructed of tan terra cotta emblazoned with symbols of the brewing industry, with the exterior bathed in gold leaf and crowned by a magnificent art glass dome. After the fair, Captain Pabst had the entire structure dismantled, crated, sent to his Milwaukee residence, and rebuilt as a private conservatory.

The facts show that Capt. Pabst came to the World’s Fair with his Blue Ribbon marketing campaign already in his back pocket. In 1892, a year before the World’s Fair, the company purchased nearly one million feet of silk ribbon, and workers were already hand-tying the ribbon around each bottle of the company’s flagship brand, Best Select Beer, to make their brand stand out at saloons. The strategy was paying off as patrons started asking their bartenders for the blue ribbon beer. The world’s fair contest added the legitimacy Pabst needed to promote his beer as a true blue ribbon winner. In 1895 “Blue Ribbon” was officially added to the Best Select brand name and in 1899 the brand name was officially changed to Pabst Blue Ribbon.

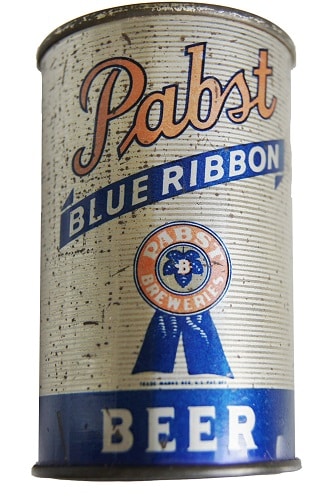

Recent scholarship, however, has called Pabst’s boasts into question. The company was forced to change the claims on its website’s timeline from “Pabst was awarded the blue ribbon at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, beating out many other popular American brewers” to “In 1882, Pabst added pieces of blue ribbon tied around the necks of Best Select beer bottles.” There is no longer mention of the brewery winning the blue ribbon at the 1893 Columbian Exposition. The company, however, continued to build on this story, long after the Captain’s death in 1903. The iconic blue ribbon became a permanent part of the label after prohibition in the 1930s when it appeared on Pabst’s new high-tech distribution method, the “can.” It continues to represent a defining element on their easy-to-identify blue ribbon label with the original claim: “Selected as America’s Best in 1893.”

Surviving Prohibition

Prohibition crippled a thriving brewing industry in the United States. Between 1900 and 1913, beer production in the United States rose from 1.2 billion gallons to 2 billion gallons. By 1916, there were approximately 1,300 breweries in the country; but four years later, a nationwide ban on alcohol went into effect.

The breweries that survived prohibition did so by retooling their operations and producing non-alcoholic beverages and other food products. Anheuser-Busch made over two dozen non-alcoholic Prohibition products (including a non-alcoholic malt beverage called “Bevo”), ice cream, soft drinks, and used its factory space for the production of truck bodies. Family-owned Detroit-based Stroh’s made malt syrup and ice cream. Pittsburgh Brewery survived Prohibition by making “near beer” and ice cream, in addition to running a cold storage facility. Coors became one of the leading producers of malted milk, which was sold to soda fountains and candy companies, and marketed as a food for infants.

Pabst Brewing Company was no different. The company leased part of its plant space to motorcycle manufacturer Harley-Davidson, purchased a soft drink company, and sold malt syrup. The brewery also adjusted by making the next best thing for Wisconsinites … cheese, branded Pabst-ett. Pabst sold over 8 million pounds of Pabst-ett cheese during Prohibition. In 1933 it sold the cheese operations to Kraft so the company could return to what it did best, brewing and selling beer.

Of the 1300 breweries in operation before Prohibition, only 100 survived. A year after Prohibition was repealed in 1933, Pabst’s sales broke the 1-million-barrel mark, and the blue ribbons were once again tied around the neck of the bottle, a custom that endured from 1933 until 1950.

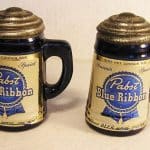

From brand apparel to “beer gear,” accessories, specialty products, and branded items for the great outdoors, fans and collectors of Breweriana and Pabst have and continue to find plenty of old and always new items to add to their collection.

For the most part, Pabst-branded items can be readily and inexpensively purchased online on eBay or found at flea markets by collectors and enthusiasts of the beer, the brand, and the many crossovers to be found in a Breweriana collection. Most of these items are too contemporary to be deemed antiques or vintage, and can be found for as little as $10 up to a few hundred for good neon and tin signs. A Google search uncovers a staggering array of Pabst-branded merchandise. Serious collectors, however, love vintage Pabst cans, bottles, trays, and signage from the mid-20th century. Some of the most desired collectibles are vintage Pabst bar statues with their miniature, striped-shirted bartenders serving up frosty mugs of fake beer, plus pre-1900 bottles and advertising.

With the brand still going strong even after all these years and under new management, one has to wonder what the next desired item will be for many Breweriana collectors. How about the “Sixer,” a Pabst-branded jacket that doubles as a beer cooler? This jacket turns its wearers into a mobile 12-pack with 11 compartments – and the 12th assumed to be held in your hand. This could turn out to be a popular collectible for many reasons and is expected to be available in the near future.

Related posts: