By Erica Lome, Ph.D.

In 1827, an obituary posted in the Concord, Massachusetts, newspaper Yeoman’s Gazette noted the passing of Thomas Dugan, a yeoman, or land-owning farmer. The obituary did not mention Dugan’s accomplishments or family, nor did they describe his character – which a later source called “industrious and a peacemaker.” Instead, whoever published the notice included only the details of Dugan’s life before he came to Concord: “He was formerly a slave to a Mr. Solomon Ward in Virginia, whence he absconded about 40 years since; and has since resided in this town.”

This reminder of Dugan’s former enslavement was possibly the work of a jealous neighbor who named Dugan’s enslaver as a deliberate attempt to alert him to the location of Dugan, allowing a claim on the estate. Dugan owned his own land, including cattle, and got his living through farming and selling dairy products to the local market. Most importantly, he died without any debts; fewer than half of his Concord contemporaries—white or Black—could say the same. Despite attempts to limit Dugan’s accomplishments, this free Black yeoman secured a legacy for himself and his family, many of whom continued to live in Concord and whose names remain a visible part of Concord’s landscape.

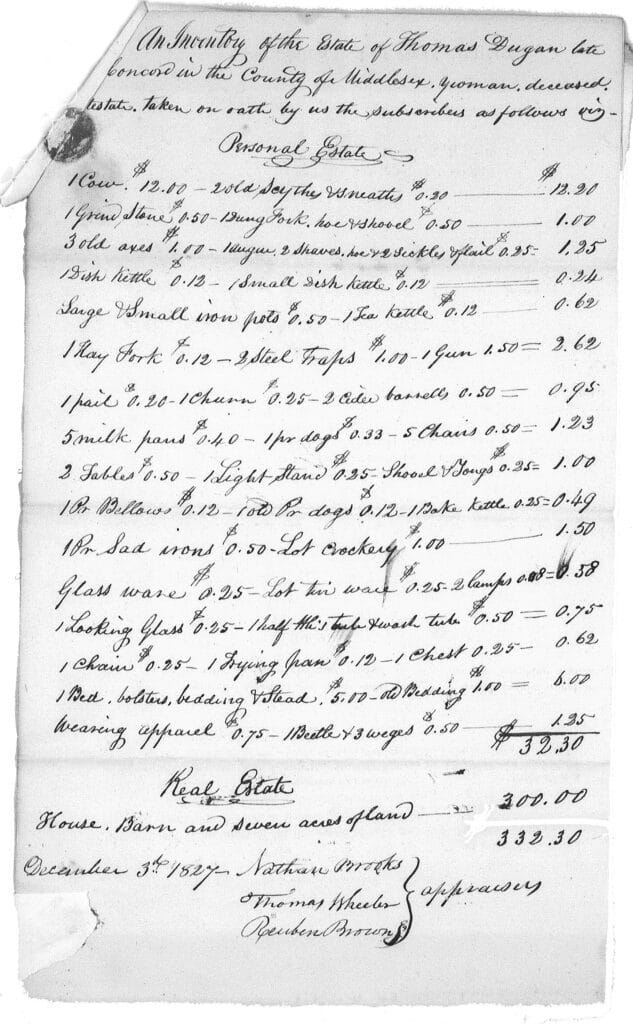

A probate inventory taken after his death reveals much about Thomas Dugan’s life and labor in Concord. Probate inventories tallied the value of possessions belonging to a deceased person—land, buildings, ad furnishings—to settle debt and distribute property to heirs. For historians and curators, this information can be useful when researching people who are difficult to find in other sources of recorded history. However, because not all household items were listed on inventories, the snapshot is almost always incomplete, and there is no reliable formula for determining what may be missing. Inventories nevertheless can give us a compelling view of daily life in a place at a given time. Thomas Dugan’s inventory is a particularly rare survival because it provides readers a glimpse into the household of a free Black farmer in early nineteenth-century Massachusetts.

“The Greatest Source of Wealth”

“Agriculture is the greatest source of wealth to the town,” wrote the Concord historian Lemuel Shattuck in 1835. When he wrote those words, farming was indeed Concord’s primary source of income and had been for generations. Concord’s fields have been farmed essentially without interruption for three thousand years. The Native communities of Musketaquid (“the place of grass or reeds”) shaped the landscape through hunting, gathering, and farming practices for fifty generations.

Throughout the 1700s, Concord farms tended to be about sixty acres, which were divided into plowlands for crops, pasture for summer grazing, meadow for hay for the winter, orchards for fruit and cider apples, and woodlots for fuel. In the later 1800s, the introduction of coal for fuel allowed farmers to convert woodlots to plowland and Concord was almost entirely deforested.

Thomas Dugan arrived in Concord around the 1790s, at a time when the population of free and newly emancipated African Americans hovered steadily around 30 in a town of 1500. Over the next thirty years, free people of color settled in the places they could afford and established their own independent households. Three neighborhoods gradually took shape far from Concord’s prosperous center. The first was at the edge of the Great Meadow, where over-farming and overgrazing depleted the soil by 1830. Another was at Walden Woods, though the land surrounding Walden Pond was generally too dry to grow crops. Thomas Dugan and his wife Jenny settled half a mile from the Sudbury meadows, south of the town center. Their seven-acre parcel of land was a sandy knoll covered with scattered tufts of grass, which locals called the “Dugan Desert.” Each of these places lacked the natural resources available to more prosperous, white-owned farms, yet Dugan earned a comfortable living. More importantly, the title of yeoman (used to describe Dugan in his probate) conferred a level of distinction given to property-owning farmers which reflected their elevated social status. This descriptor suited Dugan’s material accomplishments and reputation as “industrious and a peacemaker” within his community.

Worldly Possessions

A survey of Thomas Dugan’s inventory details the material possessions of a middling farmer in early 19th century Massachusetts and provides a closer look at the social and economic landscape Dugan navigated as a free Black man in rural New England.

The Dugan property in 1827 included a house, barn, and seven acres of land valued at $300. A cow appraised at $12 was Dugan’s most valuable piece of personal property. Dugan’s seven acres was only enough land to supply his cow with grazing feed in the summer and cut hay in the winter. He used a dung fork, hoe, and shovel to accomplish tasks like moving manure around the farmyard, weeding, and digging.

The most interesting farming tool left behind was a rye cradle, a hybrid of a scythe and rake that cut and gathered a sheaf of grain with one stroke. Rye cradles did not appear to exist in Massachusetts prior to the 1790s, but they were commonly used for agriculture in the South. Hailing from Virginia, Dugan introduced the rye cradle to Concord, where it became a staple in most farming households.

In the Dugan household, milk was made into butter, which, when salted, could keep far longer than milk. The Dugan family separated lighter, denser, fattier cream from milk and then used their churn to beat the cream into butter. Dugan’s probate inventory includes milk pails ($0.40), a butter churn ($0.25), and other accessories for processing and storing food.

Serving food took another set of objects, and the Dugan household included two tables ($0.50) with leaves that could be folded up for use or down for storage and five chairs ($0.50), a normal quantity for a smaller household of this period. Dugan might have owned simple plank-seated chairs, or, like many of his Concord neighbors, he might have had older, used furniture. A specified lot listed as crockery ($1.00), like earthenware bowls and drinking vessels, and glassware ($0.25) helped set the table for meals. A light stand ($0.26) supported a candle or lamp ($0.08), but light also came from the fireplace. Life in a New England home centered around the hearth. A fire burning day and night, year-round, was essential for chores, cooking, and staying warm. Dugan owned a shovel and tongs ($0.25), a pair of “dogs” ($0.33), referring to andirons, and a pair of “Sad irons” ($0.50) used to iron clothing and bedding after being heated in the fire.

During this era, bedding was often the most valuable item of personal property in any estate. Dugan’s inventory lists a bed, bolsters, bedding, and bedstead at a total of $5.00; only his cow was worth more than his bed. Textiles were expensive to buy and took much time and labor to make; they retained some value even after a great deal of use, which is why the inventory also lists “old bedding” at $1.00. Dugan stored his bedding and linens in a chest of drawers ($0.25), the cost of which was less than everything it contained. Shirts and stockings might be made at home, but coats were complicated and normally required the services of a tailor. Dugan’s “wearing apparel” was worth $0.75. A man’s everyday clothing in 1827 included a coat, vest, breeches, stockings, and shirt.

Another intriguing item in the Dugan estate was a looking glass, valued at $0.25. The term “looking glass” means mirror. Looking glasses were expensive to produce, owing to the complex glass-making process that took place in England. The wooden frame was comparatively easier to produce and cheaper to purchase, so the real value of such an object was the glass itself. The twenty-five-cent value of Thomas Dugan’s looking glass suggests it was not very large, but that was not necessarily the point. This was a decorative object with no significant utilitarian value. This looking glass not only reflected Thomas Dugan and his family, but it reflected their middling status in the Concord community.

In addition to farming, Thomas Dugan also hunted. His inventory lists two steel traps and a fowler, valued at $1.50 in 1827. This fowler is Dugan’s only surviving documented possession. A long-barreled musket with an unrifled barrel, the fowler was used like a modern shotgun. During the eighteenth century, fowlers like these were often modified by their owners to use in the militia by adding a steel tab to attach a bayonet. Many of the militia and minutemen who fought the British Regulars in Concord on April 19, 1775, were farmers, including people of color like Case Whitney, who followed his enslaver to the North Bridge and later emancipated himself through his service in the Continental Army. The Militia Act of 1792 prohibited African Americans from serving in the militia, so Dugan’s fowler retained its sole hunting function.

Historically, an inventory did not capture every single household item. For instance, objects of sentimental value but no monetary value were usually excluded. Other omissions from Dugan’s inventory raise questions. Dugan’s wife Jenny lived in the home at the time of his death, but no possessions specifically belonging to her, such as clothing, are listed. There are no books listed, though they may have been present. Thomas Dugan was enslaved in Virginia where literacy laws prohibited the instruction of reading and writing to enslaved people. It is unknown if Dugan learned to read later in his life.

The Dugan Legacy

Thomas Dugan’s family made a lasting impression on Concord. Jenny Parker Dugan, Thomas’s wife, inspired the name of a brook and street. A poem by Henry Thoreau mentions Elisha Dugan, son of Thomas and Jenny. Elsea Dugan, daughter of Thomas and his first wife, Catherine, is buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery. The Civil War monument in Concord’s center bears the name of George Washington Dugan, Thomas, and Jenny’s son. George was a member of the famed 54th Massachusetts, the first regiment to enlist Black men during the Civil war. He was one of the many men missing in action after the 54th’s renowned attack on Fort Wagner in South Carolina.

Very often, the faces and names associated with the history of agriculture belong to white men; farmers of color, including women, remain pushed to the margins because only a few had the opportunity to leave written records of their thoughts and activities during their lives. In a new gallery, Thomas Dugan: Yeoman of Concord, the Concord Museum reconstructed Dugan’s estate using objects from the Museum’s collection of local history artifacts as well as Dugan’s own fowler. This permanent exhibition represents the material possessions of Dugan’s estate and allows the life of a Black farmer in Concord to reenter the historical record.

Thomas Dugan: Yeoman of Concord is one of 16 newly redesigned and interactive galleries at the Concord Museum. For more information, visit www.concordmuseum.org

Erica Lome, Ph.D. is the Peggy N. Gerry Curatorial Associate at the Concord Museum.

Related posts: