By Kaitlin Servant

Farmer’s Almanac, 1793.

Early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise.” This well-known piece of advice was attributed to Ben Franklin and appeared in Poor Richard’s Almanack (sic) in 1735. The American farmer’s almanacs that readers have come to know and love have included anecdotes, poetry, pleasantries, stories, and proverbs along with long-range weather forecasts for over two hundred years. Farmer’s almanacs have a special place in Americana, but almanacs have been published all around the world for hundreds of years before Europeans began settling in North America.

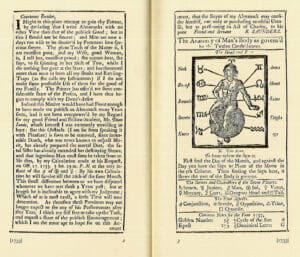

An almanac is an annual publication of current information about one or multiple subjects. It offers information such as weather forecasts, timetables for the rising and setting of the sun and moon, eclipses and meteor showers, farmers’ planting dates, tide tables, moveable holidays, and other tabular data often arranged according to the calendar. For centuries farming was not a hobby for most, but a matter of life and death. Almanacs were considered an important tool farmers would use to plan for the coming year.

The invention of the printing press made almanacs accessible to more people, but they had already existed for centuries.

Ancient Times

Long before Europeans made their way to America, almanacs existed in countries all over the world and in many languages. It is no secret that ancient people tracked the movement of heavenly bodies. The earliest almanacs were tables that tracked the position of the sun, moon, planets, and stars. Tablets dating back to the fourth century BCE and used by the Babylonians applied complex formulas to predict the movement and position of Jupiter. Nostradamus published a series of almanacs in the 1550s with his own prophetic visions and wisdom.

The word “almanac” first appeared in a treatise by the English philosopher Roger Bacon in 1267 where it referred to a set of tables detailing movements of heavenly bodies including the moon. The Italian form is almanacco, French almanach, and in Spanish it is almanaque. According to the New English Dictionary, the word is probably connected with the Arabic al-manakh and the Latin manacus, a sundial.

By the late 16th century, almanacs were outselling every English-language book except for one: the Bible. It was around this time they started offering advice on farming such as favorable dates for planting or harvesting crops and breeding livestock. They also made long-range weather predictions similar to today’s almanacs.

Colonial America

It wasn’t long after English settlers arrived in America that almanacs appeared and quickly gained popularity. In 1639 An Almanac Calculated for New England was first published by William Pierce in Cambridge, Massachusetts. By the later part of the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th century, more and more almanacs began being published in cities throughout the colonies. Nathaniel Ames of Dedham, Massachusetts, and James Franklin of Rhode Island began publishing popular almanacs in 1726 and 1728 respectively.

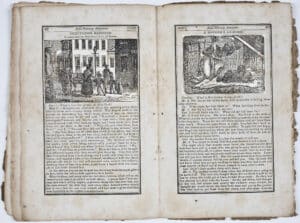

But it was Benjamin Franklin himself, brother of James, who began publishing one of the most popular almanacs of this time period. Poor Richard’s Almanack entertained and instructed its readers for more than 25 years from 1732 until 1757. It was a sensation and reached more than 10,000 readers per issue. In addition to the tables and weather forecasts people had come to expect, he included puzzles, poetry, proverbs, and a running story that encouraged readers to anticipate the following year’s edition.

By 1816 it is estimated that over 500 different almanac titles were being published. The term “farmer’s almanac” was being used generally the way we use the word “dictionary” today. They were localized and differentiated themselves by their editors. George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were known to record their daily activities in their copies of the Virginia Almanac.

Eventually, the Old Farmer’s Almanac founded by Robert B. Thomas in 1792, and the Farmer’s Almanac founded by David Young in 1818 proved themselves to be the most durable. Both have been predicting the weather, offering advice, and entertaining readers for over 200 years and are still in production today.

20th Century

American folk singer Lee Hays once said “Where I come from, a family had two books. The Bible to help ‘em to the next world. The Almanac, to help ‘em through the present world.” By then, almanacs had firmly found their place in Americana.

In the 1930s President Franklin Roosevelt used the Old Farmer’s Almanac several times to convey motivational and upbeat messages to the American public. A decade later, in 1942, the publication’s record of continuous publication almost took a hit when a German spy was apprehended in New York with a copy of that year’s Old Farmer’s Almanac in his pocket. Concerned that the almanac was providing information to the enemy its editor had to convince the FBI that it was not violating the “Code of Wartime Practices for the American Press.” The story has become part of farmer’s almanac folklore.

Throughout the 20th century, almanacs remained popular, and their readers were nothing if not devoted. In Robb Sagendorph’s book America and her Almanacs: Wit, Wisdom & Weather 1639-1970 he informs the reader that almanacs, once published, seldom changed their format. “… once an editor had introduced himself and his almanac to the public he pretty much had to stay with the contents and arrangements of his first edition.” He shared the following letter from a farmer after a minor change to the heading of the moon column on the calendar page of the Old Farmer’s Almanac.

Dear Sir:

I have read The Old Farmer’s Almanac for the last seventy-five years and I wish the damned fool that changed the heading of the Moon’s place column had died before he done it.

Yours respectfully, F.C. Crawford

Strange But (Probably) True

Over the years, almanacs have dispensed quite a lot of advice to their readers. While it may or may not all be 100% correct, it is at least generally plausible, with the implication that someone, somewhere along the way, believed it to be true. For example:

• For arthritis: Pack a small jar with golden raisins and cover them with gin. Eat nine raisins every morning, squeezing the extra gin back in the jar.

• To prevent a cold: Boil a whole onion, and afterward, drink the water.

• For brittle nails: Eat Jell-O.

• To avoid dying: Absolutely no haircuts in March, don’t sing in bed, don’t cook your own birthday dinner, never serve 13 at a table, don’t walk backward, never count the cars on a passenger train, don’t let two people comb your hair at once, and don’t walk around in one shoe.

Collectible Editions

While most older editions of farmer’s almanacs are not particularly valuable. This is especially true of the prolific Farmer’s Almanac and Old Farmer’s Almanac which have been in print in the United States for over two hundred years and could be found in just about any rural home. It is common to find old boxes filled with years and years of older editions. Even antique copies from the 18th century are not particularly rare and due to the high rag content in the paper used they have held up relatively well.

There are some notable exceptions. A 1733 copy of Benjamin Franklin’s Poor Richard Almanac was discovered by the historical society of Berwick, PA in 2009. Initially, experts estimated it was worth $7,000-$10,000–but after the Library Company of Philadelphia determined it was one of only three known copies of the 1733 edition to exist–it ultimately sold to an anonymous bidder for $556,500. At the time, it was the second-highest price ever paid for a book printed in the United States.

Large collections with rare early copies can fetch high prices but the vast majority of copies are not worth more than $10-$15. But that doesn’t mean they aren’t a fun and interesting item to collect!

Museum Collections

One of the largest almanac collections is held by The American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts. The collection contains over 15,000 almanacs printed from 1656 through 1876 and the Society is still actively acquiring missing titles and issues. It is the most comprehensive collection in existence and includes about three-quarters of all the almanacs published in North America during the 220-year period.

The New York State Library contains a large collection of almanacs as well. It includes over 10,000 almanacs from 1684 to the present. In addition to some of the more common farmer’s almanacs like Poor Richard’s Almanac and the Old Farmer’s Almanac, the collection includes specialty and niche almanacs such as Almanac of the American Temperance Union, Anti-Slavery Almanac, Boys’ Almanac Containing Fun and Entertainment for Young and Old, Farmer’s and Farrier’s Almanac, Davy Crockett’s Almanack, Illustrated Phrenological Almanac, and the intriguing Tragic Almanac.

Today

Farmer’s almanacs have stood the test of time and are still popular today. In a time when very few people farm their own food, the nostalgia of the almanacs and their wit and wisdom have kept them in readers’ hands.

The Farmers’ Almanac website provides an explanation for their continued popularity. “The reason is simple; smart living never goes out of style.” Today’s readers may not be farming to survive, but they care about the environment and conservation. The Farmers’ Almanac, does and always has, provided them with hacks and sustainability to help them live a greener life and stay connected to the natural world around them. Something that today’s smartphones don’t always deliver.

And to keep up with the times, both the Old Farmer’s Almanac and the Farmers’ Almanac have embraced the digital age. With robust websites and strong social media followings, the two longest-running American farmer’s almanacs are still entertaining and delighting new audiences today.

Related posts: