by Erica Lome, Ph.D.

On a cool April morning in 1775, Amos Barrett readied his musket and prepared for combat. Earlier that day, 23-year-old Barrett had awoken to the news that 700 British Regulars were marching from Boston to Concord. They were planning to seize and destroy military supplies stockpiled by “rebellious” Provincial colonists as tensions with the British government worsened.

He Was Not Throwing Away His Shot

Barrett was a member of the Concord Minute Company, a special corps ready to fight “in a minute,” created by the Massachusetts Provincial Congress in 1774. By the time he made his way to the muster field, the Regulars had already opened fire in Lexington, killing several members of the opposing militia and wounding more. They were now in Concord searching for the contraband material, while about a hundred men each went to secure the nearby bridges. At the North Bridge, 450 Provincials had assembled to stop their progress. Amos Barrett was among those who, upon seeing the Regulars approach, changed the flints in their muskets – a clear and deliberate provocation. In an account written fifty years later, Barrett described what happened next:

We were all ordered to load and had strict orders not to fire till they fired first, then to fire as fast as we could. We then marched on. Capt[ain] Davis had got, I believe, within 15 rods of the British, when they fired 3 guns, one after the other. I see the balls strike in the river to the right of me—as soon as they fired them they fired on us, their balls whistled well. We then was all ordered to fire that could fire and not kill our own men.

The ensuing “shot heard round the world” set in motion a day-long conflict that marked the beginning of the American Revolution.

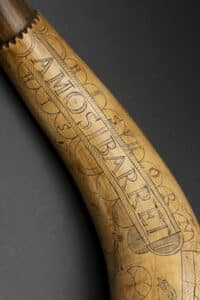

To commemorate the occasion, Amos Barrett carved “April XIX” and “1775” into his powder horn, which already contained engravings of animals, a ship, compass, and other geometric designs. That powder horn remained by Barrett’s side for the rest of his life and became a prized family heirloom before entering the collection of the Concord Museum.

Powder Horns: The Mark of a Revolutionary Man

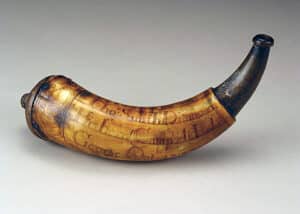

Powder horns, vessels made from ox or cattle horns, carried gunpowder and were an essential part of colonial American military culture. They could also be unique works of art, engraved with ornate designs and inscriptions made by professional artisans working in military camps. Their owners, many of them simple farmers and townspeople, observed and participated in the events that would shape a young nation. They were at once personal and professional artifacts, documenting not only the violence and impact of military conflict but also the humanity and imagination of its participants. Let’s take a closer look, shall we?

Early Period Powder Horns

In Colonial America, as elsewhere in the early modern Atlantic world, cow horns were used for a variety of purposes. People drank out of horn cups, brushed their hair with horn combs, and dipped their ink into horn containers. As waterproof and fireproof vessels that could be scraped and hollowed out, they were extremely functional and relatively inexpensive to obtain: the raw materials were often sold cheaply from local tanneries.

Anyone who owned a musket, fowler, or rifle used a powder horn. Since the c employed a flintlock mechanism, which ignited gunpowder by striking steel with flint. As flintlock weapons became standard, powder horns become an essential component of the Provincial uniform. Horns containing gunpowder were fitted with a plug in the base end and a smaller plug or stopper in the spout. The curved form of the horn fit around the waist of its user comfortably, enabling easy access when worn with a long strap over the shoulder. Whether for hunting or fighting, all you needed to do was tip a little gunpowder into your weapon and you were good to go.

During the mid-eighteenth century, ongoing and successive military campaigns between the British, French, and the Native peoples of North America brought powder horns and their owners into uncharted territory. Within the camps and forts of northern New England, upstate New York, and the Great Lakes region, a formal artistic tradition of horn carving began to emerge. On a very basic level, decorated powder horns became a means of personal identification for soldiers. Inscribing one’s name into a horn helped distinguish one horn from another as they were filled with black powder from a large keg or barrel. Lower-ranked troops could not always read or write, so having one’s name on an object symbolized education and status. The final product was not always a success as many powder horns contain phonetic or misspelled names of their owners.

The Craft and the Art

While some soldiers carved their own horns, it was far more common to seek out a professional carver, many of whom were engravers and followed the troops to various forts and battlefields. Mostly anonymous, these makers could complete a horn relatively quickly and faced high demand from soldiers hoping to match the fashionableness of their peers. Carvers first sketched out their design and then used a knife, graver, or needle to incise the pattern on the surface of the horn. Soot or veggie dyes might be applied to create a polychrome or shaded effect.

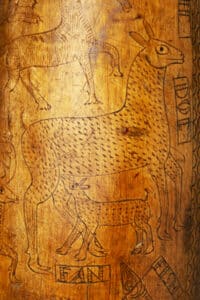

Some of the earliest decorated powder horns were produced during King George’s War (1744-1748) and featured gothic lettering, animal figures, foliate decorations, and geometric designs. One example belonged to Stephen Parks of Concord, who had his horn decorated in 1747. It is one of a set of powder horns whose carvings are attributed to the same anonymous maker who drew heavily from European design precedents. The horn is engraved with various forms of wildlife including owls, fish, deer, moose, rabbits, foxes, and even unicorns. These real and fanciful creatures speak to the imagination of soldiers venturing into uncharted territory.

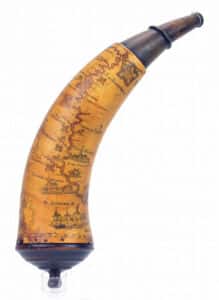

Another wonderful example can be seen in a horn owned by Captain James Hawell, who evidently traveled the Hudson River North from New York City to Albany and parts beyond and engraved this route on his horn, dated July 14, 1760. A map of the Hudson River winds around this fifteen-inch horn, splitting above Albany on one side to follow the Mohawk River to Lake Ontario and, on the other side, continues with the Hudson to Lake Champlain. Along the way, the engraver included over two dozen towns and forts, each one named and rendered with exquisite and individually distinct architectural features. Like the previous example, Captain Hawell likely sought this design as a record of his experiences to show to family and friends back home.

Innovation and Influence: John Bush

A skilled horn carver could execute original patterns for their client, but most based their decorations on other powder horns in their camp. If one artist produced a compelling product, others would replicate and adopt the same design. This often resulted in artistic cohorts whose output is, today, grouped together based on shared visual traits, even in the absence of their signatures. Such a phenomenon took place in the military camps south of Lake George led by John Bush, a master of the genre whose decorated powder horns influenced an entire generation of artisans.

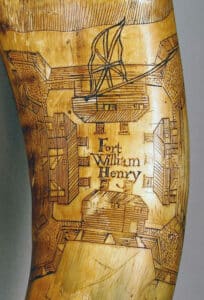

Born in 1725, Bush was a free man of color from Shrewsbury, Massachusetts who served as a soldier and clerk with the Massachusetts militia during the French and Indian War and was stationed at Fort William Henry between 1755 and 1756. It is unknown where or when he learned to carve, though extant powder horns suggest there were carvers in Shrewsbury in the 1740s when Bush was a teenager.

There is only one known powder horn signed by Bush, though many others are credibly attributed to his hand. The signed horn, made September 8, 1755, bears Bush’s signature, along with the inscription about its owner Thomas Williams, an army surgeon, and a short poem:

When Bows and weighty Spears were used in Fight / Twere nervous Limbs Declard men of might / But Now Gun Powder Scorns such Strength to own / And Heroes not by Limbs But Souls are Shown.”

Another horn owned by William Williams, nephew to Thomas Williams, bears strikingly similar decorative elements and calligraphy to the one above. Though unsigned, it was almost certainly carved by John Bush. His trademark elements are all there, including the clean and bold calligraphy with decorative flourishes surrounded by scrolled or foliated borders.

Bush’s decorated powder horns laid the groundwork for what’s now regarded as the Lake George School. His calligraphic style and decorative devices were copied by other artists in the camps, including the Selkrig-Page Carver, the J.W. Carver, and the Memento Mori Carver. In 1757, Bush was captured during the surrender of Fort William Henry, likely by Native allies to the French. Despite his family’s repeated petitions to the Massachusetts Governor for their help in locating him, Bush was never heard from again. Yet, in the two years he served in Lake George, Bush secured his legacy as one of the most important and influential powder horn carvers in Colonial America. In fact, powder horns carved after the French and Indian War retained several of his signature elements, suggesting that many of his decorated horns were brought back to Massachusetts and traveled with their owners into subsequent military conflicts.

The End of an Era

The final so-called “phase” of the decorated powder horn tradition in Colonial America took place during the Siege of Boston (1775-1777). After the inciting events at the North Bridge in Concord, Amos Barrett and his fellow minutemen joined thousands of Provincial soldiers from across Massachusetts to confine the British Army to Boston for over a year – a siege that ended with the Battle of Dorchester Heights and the evacuation of British troops from the city.

Concord Museum Collection, Gift of Mrs. Robert M. Bowen (1972).

Powder horns carved during the Siege depicted what Provincials soldiers themselves saw during the conflict. Typical subjects included sketches of fortifications, city views, and Provincial encampments in Roxbury, Charlestown, and Cambridge. Horns also depicted soldiers marching and engaged in battle, along with the weapons and accouterments of war. Patriotic vignettes and imagery abounded, often used as decorative devices surrounding inscriptions. While calligraphy wasn’t as important a feature during this period, horns with lettering perpetuated the style popularized by John Bush and the Lake George School.

One horn from this period belonged to Jonathan Gardener, who served in the Massachusetts militia and was present in Roxbury and Dorchester Heights in 1776. He had his horn carved and inscribed with his name, date, and the patriotic slogan “Liberty & Property or Death.” Images included fourteen soldiers marching single file—some carrying weapons, others a fife and drum—and, on the opposite side, two ships with tall masts. The leftover space is filled with geometric and whimsical designs of animals, human faces, and compasses.

After 1777, the Continental Army, led by George Washington, equipped more troops with cartridge boxes, a far more efficient method of supplying and loading gunpowder. As a result, fewer soldiers carried powder horns, and the art of engraving them began to wane. Those carved after the Revolutionary War were created to serve as mementos of a conflict or, in some cases, were fabricated to establish credentials as a veteran. In the early 19th century, one might even use a decorated powder horn to falsify their patriotic lineage.

Military powder horns became obsolete with the standardization of the percussion lock system in firearms in the early 1800s, replacing the older flintlock mechanism. Similarly, as gunpowder came to be stored in self-contained metallic cartridges, there was no longer a need to carry the black powder in a personalized vessel. While still used occasionally for hunting, these former military objects and their associated artistic tradition ended at the dawn of modern warfare.

Colonial Revival and Collecting Interest

By the late 19th century, the revival of interest in America’s colonial history resulted in decorated powder horns becoming a popular collector’s item. Credit must be given to the antiquarian Rufus Alexander Grider, who made hundreds of illustrations of decorated horns during his excursions through the Mohawk Valley between 1886-1900. These drawings, published and circulated widely, reproduced the inscriptions and detailed designs found on engraved powder horns and demonstrated their merit as works of art. Since then, powder horns have intrigued collectors of military history, folk art, and colonial America.

The contemporary market for powder horns is robust, with many private collectors, museums, and historical societies vying for a piece of Revolutionary history. Values are based on condition, the type of carving, and, importantly, attribution to a known carver or owner. Simple horns with just a name and date might be worth a few hundred dollars, while more sophisticated examples command thousands, even tens of thousands of dollars. Meanwhile, new generations of living historians have continued the art form for recreation or public reenactments of historic battles.

The beauty of decorated military powder horns is the story each one can tell about their owners, carvers, and the places and people they encountered. They are not merely a record of military service but unique works of art that have stood the test of time. More than that, they show that beautiful things can come from the simplest of objects with a little patience, skill, and imagination.

Erica Lome is currently the Peggy N. Gerry Curatorial Associate at the Concord Museum, sponsored by the Decorative Arts Trust. She holds a doctorate in history from the University of Delaware and a MA in decorative arts, design history, and material culture from the Bard Graduate Center.

Related posts: