by Erica Lome, Ph.D.

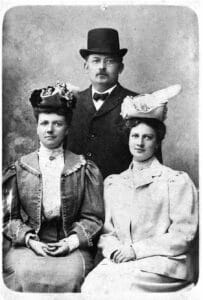

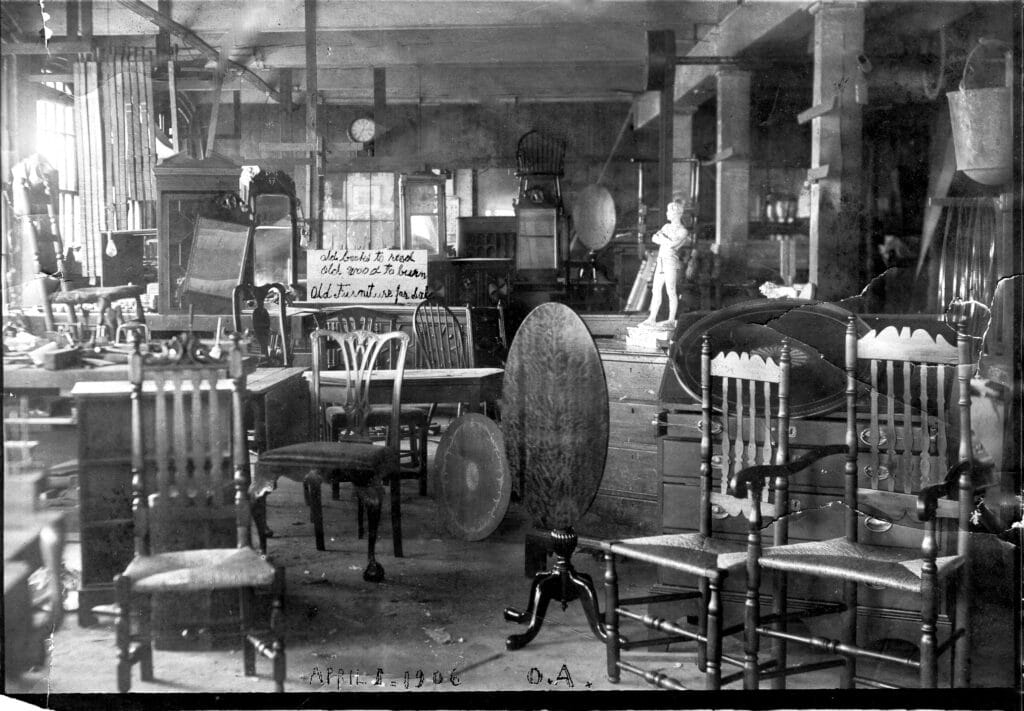

Today, few people outside of the antiques trade recognize the name Olof Althin (1859-1920), a Swedish-born cabinetmaker active in Boston at the turn of the twentieth century. Known primarily for his beautiful carved furniture and his accurate reproductions of antiques, Althin was also responsible for restoring two of the great collections of Early American furniture, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. To the delight of this historian, Althin left behind his business records, furniture designs, objects, woodworking tools, and personal effects, in addition to his workbench. These rare survivals will be featured in the upcoming exhibition, American by Craft: The Furniture of Olof Althin, at the American Swedish Historical Museum this summer. Together, they help to tell the story of a creative, industrious immigrant working at the peak of America’s craft revival.

Across the Pond

photo: Winterthur Library

Olof Althin’s story began as a familiar tale of immigration to America. Born in Sweden, Althin trained as a cabinetmaker through a traditional apprenticeship, learning to make furniture by joining, turning, and carving wood by hand. Rather than remain in the farming village of Nobbelov, the potential for upward mobility brought 22-year-old Althin to Boston in 1881. The location and timing were auspicious: by the late nineteenth century, Boston had emerged as a center of the American Arts & Crafts movement, home to a cohort of designers and educators looking to reform society and manufacturing through the promotion of traditional handicrafts.

Boston was also far more welcoming to immigrant cabinetmakers, professionally speaking, than other American cities. While large factories and industrialized production in the Midwest had all but obliterated the small cabinet shop in places like New York or Philadelphia, Boston retained a strong local furniture market, reflecting the tastes of its wealthy, socially elite community. These customers preferred quality, handmade furniture – and by the end of the 19th century, most American-born workers lacked the training to produce them. Skilled foreign craftsmen quickly moved to fill this vacancy and came to dominate the high-end furniture trade in Boston and elsewhere in the United States.

Despite fierce competition from his fellow Swedes and other immigrant groups, young Olof Althin secured employment at the cabinetmaking firm Evans & Toombs before becoming the foreman at Doe, Hunnewell & Co, which made furniture and wooden mantels. By 1886, he had enough capital to open his own business, O. Althin Art Furniture & Interior Fittings, on Albany Street in Boston’s South End. Althin’s small shop, which only employed six to nine other workers, specialized in architectural fixtures and “art furniture,” meaning custom pieces made to order.

Furniture Portfolio

A survey of Althin’s furniture made between 1886 and 1913 (the year he retired) reflects the full range of styles popular in Boston during the late Victorian era, from Gothic Revival to Neoclassical, and everything in between. Althin did not align himself with any one design movement, nor did he fully subscribe to any of the prevailing artistic ideologies of the day. His strength as a craftsman was in his adaptability and ability to pivot directions according to his customers’ tastes.

Like other cabinetmakers in his day, Althin freely borrowed elements from different furniture sources and combined them to make something appear simultaneously antique and modern. The results could be subtle, like the design of a tall case clock that combined stylistic cues from both the 1740s and early 1800s, while others were more extravagant, such as a sofa embellished with elaborate carving that had no discernable precedent. Althin’s granddaughter described this eclectic style as “wild and wooly.”

Hand-Craftsmanship and Creativity

Althin and his men made furniture by hand, meaning the work of assembling, turning, joining, carving, and finishing furniture was done at the workbench, while steam-powered machines expedited tasks like smoothing and cutting wood. Unlike in an industrial factory, where a different tier of workers executed each step in the process, Althin saw each project through from beginning to end. His tools included a special hand saw to cut out dovetails in furniture, chisels to carve designs in wood, and planes to create decorative moldings.

Althin was content with his small-scale business. It allowed him some measure of creative freedom and was also a cost-efficient model that ultimately proved to be a success, thanks to his reputation as an expert woodworker. His clients included Massachusetts State Senator George Crocker, industrialist Charles Sumner, and even U.S. Postmaster General John Wanamaker, who commissioned furniture for his personal residence. For these and other clients, Althin might furnish an entire room or even a house.

By the early 1900s, the prevailing taste in Boston was for furniture in the “colonial” style, meaning the style of furniture made and used in America before and immediately after the American Revolution. The nascent trade in Early American antiques, made fashionable by the activities of historic preservationists and connoisseurs, spawned a related market for high-quality reproductions. Althin was more than qualified to fulfill those orders, reconstructing the look and feel of Chippendale or Hepplewhite furniture using similar, if not the exact same, techniques as those master craftsmen.

Examples of Excellence

photo: private collection

Take, for example, a mahogany dressing table made in the Chippendale style, with an intaglio carving of a shell in the center drawer, carved foliate designs along the apron and knees, and ball & claw feet. Althin rendered all aspects of this piece with faithfulness to the original, especially the carving – a trademark of rococo furniture made in Philadelphia between 1750-80. In fact, this piece is a dead ringer for a 1760s dressing table at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which Althin might’ve seen in an auction catalog. In many cases, he based his designs on the careful measurements he took of genuine antiques which often passed through his shop for repair.

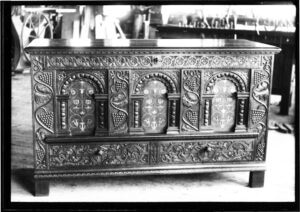

photo: Winterthur Library

Althin’s most popular products were blanket chests inspired by beautifully carved New England chests of the 1600s and early 1700s – what Wallace Nutting called the “Pilgrim Century.” Althin consulted sources like Newton Elwell’s Colonial Furniture (1896) for inspiration and infused a touch of Swedish folk tradition into the rich designs of each chest. One chest, made in 1906, contains three inlaid panels with marquetry work in a tulip and vine design, surrounded by a deeply carved pattern of grape bunches, folate designs, and strapwork. Althin listed it as “Grandmother’s Old Linen Chest” in his account book. It took over 102 hours to make, and Althin’s workers (fellow Swedish craftsmen) practiced the intricate carved elements in clay before executing them in wood. Their skill was evident to any who beheld these chests, which Althin proudly displayed in his showroom.

Althin as Consultant and Restorer

Althin was himself neither a colonial revivalist nor a collector, but his understanding of historic furniture style and construction made him the perfect antiques consultant. Two of his biggest clients were Charles Hitchcock Tyler (1863-1931) and Horace Eugene Bolles (1858-1910), cousins, law partners, and connoisseurs. From the 1890s until 1920, Althin operated as a special contractor to Tyler and Bolles, “expertising” both the quality of furniture and its veracity. He once boasted to Tyler about “the many people I have saved from getting their fingers burned in buying supposed antiques.”

Althin’s other job was to restore the old, dilapidated furniture Tyler and Bolles collected and make them look like antiques, often by replacing entire limbs or filling in the loss of details like carving and inlay. Hundreds of pieces acquired by Bolles and Tyler passed through Althin’s shop and eventually went into the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Bolles) and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (Tyler). Althin is not formally credited for this work, but cross-referencing his account books with the museum accessions provides strong evidence that Althin’s invisible hand shaped the look of these important collections of American furniture.

Althin’s handiwork was sometimes a little too evident, particularly in the case of some of the painted furniture he restored for Tyler and Bolles. One example of this is a Middlesex County pine cupboard currently owned by the Met, dating between 1675-1700. Bolles claimed his dealer found it sitting outside under a tree in Lexington in terrible condition. Early photographs corroborate this claim: the top boards of the top and base were too rotten to use, as were two drawers. The center of the door was gone, along with two of its frames. Bolles replaced these components and instructed Althin to copy the carvings from the old doors for the new ones. He also had Althin repaint the cupboard according to what he believed was the original design, and a photo of the restored version shows bright, contrasting patterns of circles and squiggly lines on the form. Luke Vincent Lockwood, who published the cupboard in his seminal work Colonial Furniture in America (1901), remarked “There is no doubt that it is restored correctly but probably too brilliantly.” Curators at the Met agreed; by the time the piece came into their hands , they stripped the paint to fit scholarly consensus of its original appearance. They left Althin’s other repairs alone.

Olof Althin walked a fine line between being an expert and an employee, deferring to Tyler and Bolles on certain design matters while also exerting control as a cabinetmaker. When Bolles unexpectedly died in 1910, Tyler wrote to Althin reminiscing about “how we used to be together mornings out to your factory. There will never be any more of those mornings.” A similar letter to Althin’s daughter Bessie after her father’s death recalled, “Both Mr. Bolles and I spent many, many happy hours with your father and I hope he had happy ones with us.” Tyler’s regard for Althin evidenced several decades of friendship and patronage.

The Immigrant As Master

Neither party forgot Olof Althin’s status as an immigrant. In 1916, Tyler remarked on Althin’s “extraordinary ability” in expressing his ideas in the language he adopted. In another from that same year, Tyler asked if Althin was born in America or if he was ever naturalized (he was, in 1895), admitting to having forgotten. These benign, even playful comments, nonetheless demonstrate that certain social boundaries persisted among members of Boston’s Old Stock and foreigners like Althin, even though Swedish-born Althin likely had an easier time navigating the antiques trade than his fellow Jewish, Italian, or German cabinetmakers before and during World War I.

Olof Althin never saw his immigrant background as a hindrance; in fact, he saw it as a benefit. His Swedish apprenticeship had given him the tools he needed to survive and prosper in America, enabling him to retire at 55 and live comfortably with his wife and daughter in Roxbury. In a different sense, Althin recognized the important role immigrant craftsmen like himself could play in his adopted country’s furniture trade. Amidst the widening divide between academically trained designers and manually trained workers, Althin believed most Americans lacked both the imagination and the training to “manipulate, contrive and form from boards and planks of wood” a beautiful piece of furniture.

Before his retirement, Althin set out to bridge this gap by writing a manuscript called Architect’s, Designer’s and Draftsmen’s Guide for the Designing of Woodwork and Furniture. Althin intended for this document to educate aspiring American designers on the fundamentals of woodworking. In his introduction, he wrote:

“I offer this book to fill the space as far as possible between theory and practice, in other words lead the draftsman with essential points of information along the lines in construction of woodwork as required by the nature of wood, known only to the one who has thoroughly learned the cabinet-maker’s trade.”

Althin’s lofty goal was never fully realized, as he left the manuscript unfinished before his death in 1920.

Olof Althin was like hundreds, if not thousands, of immigrant cabinetmakers who came to America and found success in their chosen trade. In this sense, his story is not so remarkable. The truly remarkable thing about Althin is how his story was remembered: through the preservation of his furniture, tools, and other ephemera by his descendants, including his great-grandsons, who have become custodians of his legacy. Their continued care ensures that future generations can learn about the history of craft, business, and immigration in America; but more importantly, they remind us of how objects may connect us to those long gone yet never forgotten.

American by Craft: The Furniture of Olof Althin opens July 23, 2021, at the American Swedish Historical Museum in Philadelphia. For more information, visit americanswedish.org.

Erica Lome, Ph. D., is the Peggy N. Gerry Curatorial Associate at the Concord Museum and co-curator of American by Craft.

Related posts: