by Donald-Brian Johnson

“A penny saved is a penny earned” … “A stitch in time saves nine” … “An apple a day keeps the doctor away.”

Some folks call them mottos. Or proverbs. Folk sayings. Adages. Often, they have a definite ring of truth (after all, if you save a penny, then you do indeed have one more than you started with). Other times, maybe not so much. (I’m pretty sure that “apple/doctor” thing doesn’t really work.) But verifiable or not, “words to live by” like these creep their way into our consciousness, and often into our conversations. If you tell someone, “Every cloud has a silver lining,” you know exactly what you’re saying, and they know exactly what you mean. You’ve taken a shortcut on the road to communication. Kinda trite? Well, maybe … but hey, “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

“The Pen Is Mightier Than The Sword”

Words to live by have been with us for a long, long time. They’ve been found on tablets carved by ancient Sumerians in 2000 B.C. There are plenty of proverbs in the Bible (and not just in the Book of Proverbs). Ben Franklin loved ‘em. And, in the 19th century, seamstresses perfected their needlework by stitching inspiring messages into samplers. But what separates a proverb from a motto? A folk saying from an adage? Well, let’s get to those definitions right away. After all, “time waits for no one.”• Proverb: The phrase is short, the meaning literal, and the truth or advice imparted is pretty obvious. (“Don’t bite off more than you can chew.”)

• Idiom: A group of words that typically wouldn’t make much sense together, but, thanks to continued usage, the meaning is understood. (“It’s raining cats and dogs.”)

• Motto: A statement of belief or purpose that may serve you well, if you resolutely adhere to it. (“Never mix business with pleasure.”)

• Aphorism: A concise way of expressing a “customary truth.” (“You made your bed, now you have to lie in it.”)

• Folk Saying: A sentence that gives advice or info based on human life experience. (“Charity begins at home.”)

• Axiom: An unprovable rule, accepted as true because it’s self-evident. (“Nothing can both be and not be at the same time.”)

• Adage: A somewhat antiquated means of expressing what’s assumed to be a general truth. (“Every child is beautiful in the eyes of its mother.”)

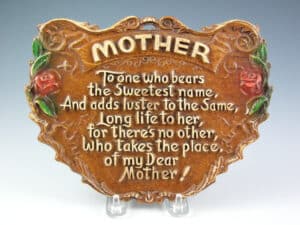

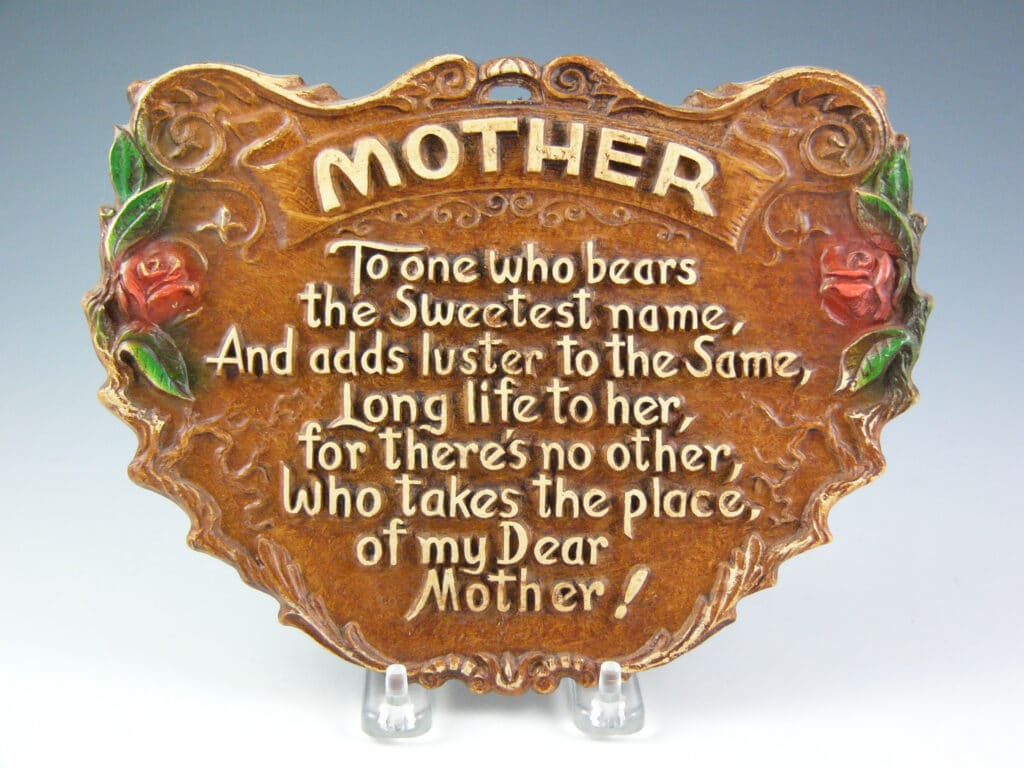

Confusing? Well, “beggars can’t be choosers,” and the boundaries are blurry. What’s important to remember is that, whether proverb, motto, or folk saying, it’s an effective means of conveying an understood and accepted message, with a metaphorical or symbolic style that transcends everyday speech. And, by the mid-twentieth century, such “words to live by” made their way into American homes, thanks to inspirational wall plaques. When folks found themselves in need of advice, encouragement, a smile, or just a pick-me-up on a dreary day, there it was, staring them right in the face.

“Necessity Is The Mother Of Invention”

Gazing at a wall plaque from the 1930s or ‘40s, you can’t help but admire the hand-carved lettering and images, often highlighted with color accents, on burnished wood backings. Had a squad of master carvers been working round the clock?

The answer is both simpler, and more cost-effective: the Syracuse Ornamental Company of Syracuse, New York (“Syroco”) pioneered the concept of molded wood décor pieces, producing near-perfect replicas of hand carving. Although the plaques looked hand-carved, and of “real” wood, they actually weren’t. Like other wood-like carved novelties of the era, these wall plaques were actually molded, pressed wood creations, putting them within the reach of almost every pocketbook. And, although numerous companies produced similar items, it was Syroco that developed the concept, and led the pack. (In fact, due to its dominance, “syroco” has since become generic shorthand for all types of pressed wood products, regardless of maker.)

So what could buyers expect from pressed wood? In the words of the 1942 Syroco catalog:

“For centuries, the most prized decorative art pieces have been carved in wood, for wood alone possesses the full, rich warmth and decorative beauty that best complements a well-appointed home. Syrocowood possesses the rich beauty of choice hand-carved wood designs, combined with practical utility.”

In other words, if it wasn’t hand-carved, it was the next best thing.

Syrocowood was a product born of necessity. In 1890, wood artisan Adolph Holstein, a recent immigrant to the United States, found his skills as an accomplished carver in great demand. Ornately carved woodwork was much in favor at the dawn of the 20th century, and Holstein’s numerous commissions extended throughout New York – even to the Governor’s mansion in Albany. Soon, more master carvers were added to the staff of Holstein’s new company, Syroco, but the time-consuming process of hand-carving limited the number of orders that could be accepted. Training additional carvers required years of apprenticeship. The answer? Syrocowood! Holstein’s solution was to create a master carving, cast a mold, and then cast replicas from that. Since only one master carving was required for each design, both production and affordability were greatly enhanced.Syroco’s oft-stated goal was to ensure its Syrocowood objects were as close to “the real thing” as possible. The effect of authentic wood was enhanced by carving each master from the specific type of wood its replicas were intended to resemble. A lead mold was cast from the carving, with the surface textured as per the grain of the original wood. The mold was then filled with a mixture of wood flour, waxes, and resins, and compressed. After removal from the mold, sanding removed mold lines, and the piece received either multi-color decoration, or a natural wood stain. As Syroco promotional materials proudly stated, “The exclusive

formula captures every delicate curve and detail of a hand-carved Syroco original.”

The look was exceptional, the cost was minimal, and the popularity of Syrocowood skyrocketed. In the company’s early years, the call was primarily for decorative furniture trim, a ready replacement for hand-carving, or for expensive, less-detailed, stamped designs. Company catalogs of the time offered furniture manufacturers literally thousands of carving design options to choose from. Syroco trim pieces soon adorned everything from caskets to armchairs and took the place of hand-carved trim molding in home interiors.

But tastes change. As highly ornamented furniture and molding trim fell out of favor, Syroco sought new avenues for its product. The first solution came with the dawn of the radio age. During the 1920s and ‘30s, Syroco became the primary supplier of radio speaker grilles, tuner knobs, and cabinet trim. A second new marketing push occurred in the 1930s, as the Syroco line of wood-like novelty items made its debut. Here, the creative impulses of Syroco carvers, and company designer Fred Fisher, could be given free rein on a dizzying array of ashtrays, door stops, dresser boxes, pen sets, picture frames, bookends, brush holders, corkscrews, bottle openers, clocks, paperweights, coasters, coin trays, desk calendars, bar trays, humidors, pipe racks, napkin rings, note boxes, thermometers, tie racks, statuettes … and motto plaques.

These were the sort of items vacationers might snap up, and that was actually the original intent. Billed as “just right for elegant living and gracious giving,” pressed wood plaques made great souvenirs. On many, there was a molded circular space, for a decal heralding the specific vacation spot where it had been purchased. Across the United States, dime and department stores began stocking them. For consumers who couldn’t afford hand-carved wall décor, Syroco was the answer.

“All That Glitters Is Not Gold”

The popularity of Syroco soon gave rise to a host of imitators: main competitor Burwood Products Co. (“Karv-Kraft”) of Michigan; the Canadian firm, Durwood; Multi-Products (“Décor-A-Wood); Ornamental Arts &

Crafts Co. (“Orn-A-Craft); and even a Syroco associate company, Ornawood.

The 1950s also saw a major shift in what exactly constituted a Syroco product, with compression molding phased out in favor of injection molding. The difference was essentially “wood-like” versus “wood-look.” Although the appearance was still of hand-carved wood, the composition was now an all-polymer blend. Resulting pieces were lighter, sturdier … and cheaper.

Whether wood or “wood-ish,” Syroco retained an ongoing appeal all its own. A particularly fanciful section in the sales booklet A Portrait of Syroco imagines Adolph Holstein musing as he painstakingly brings a carving to life: “If only there were a way to make more pieces, less expensively, so that more people might enjoy the beauty of this art. If only there were some way to reproduce the original exactly.”

Well, there was a way – and Mr. Holstein found it. Today, vintage Syrocowood plaques and other novelties do a brisk business at antique shows and online. Inexpensive in their day, pressed wood wall plaques still remain a very affordable collectible. Plenty offer up their words of wisdom daily on eBay, with most averaging under $25. Collectors should appreciate that. After all, “a penny saved is a penny earned.”

Plaques courtesy of Mark Dickmeyer

Photo Associate: Hank Kuhlmann

Donald-Brian Johnson is the co-author of numerous books on design and collectibles. His favorite words to live by: “the ultimate inspiration is the deadline.” Please address inquiries to: donaldbrian@msn.com

Related posts: