By David E. Lazaro, Curator of Textiles, Historic Deerfield

In late summer of 1741, Boston tailor Richard Billings (1699-1776) announced in a local paper a reward for the return of a runaway enslaved man known only as Exeter.1 Labeled a “Negro Man Servant,” Exeter was further defined by his captor as “work[ing] well at the Taylor’s Trade …” The ad ran for four weeks in August, and the reward went up during that month from £5 to £10. Written evidence some twenty years later suggests that Exeter was apprehended and returned to the tailor, one of four enslaved men held by Richard and his brother John (1697-1762), who was also a tailor.

The Billings brothers themselves represented at least the second generation of a successful tailoring dynasty living and working in the colonial city. Tailors like the Billings thrived in part through their use of enslaved men like Exeter who worked side by side with them, directly or indirectly, in the trade. The hidden contributions of enslaved men are revealed to us today largely through the written record (wills, probates, and newspapers), rather than surviving garments. Documenting the use of forced labor by Boston’s 18th century tailors helps reconstruct both the nature of slavery in this branch of the clothing trades, as well as the experiences of those men held in bondage. A greater understanding of the contributions of enslaved male tailors contextualizes and deepens an understanding of the profession, its working conditions, and how these men literally and figuratively worked “behind the seams” to make clothes for a white clientele in colonial Boston.

18th Century Boston and its Enslaved Population: An Overview

[Figure 1] First settled by the English in 1630, Boston quickly became the largest populated city in colonial British North America. By 1770, although it had dropped to the third-most-populous city (behind Philadelphia and New York City), Boston boasted around 15,520 inhabitants.2 Early in the 18th century, businesses were concentrated in the city’s North End, the earliest area of English settlement there. But by the middle of the century, businesses and residents were beginning to move south to the city’s central district.3 Tailors and other artisans followed suit, situating them closer to the main wharves, commerce, and customers.

Since the late 1630s, enslaved men, women, and children of African descent were a presence in Boston.4 In the following decade, the systematic trade in human lives and the use of their forced labor in the colony was established.5 By the middle of the 18th century, Boston’s estimated Black population hovered around 1,500 individuals, or almost 10% of the city’s population (15,731).6 The Exchange Tavern on King Street (later State Street) and Sun Tavern on Dock Square, were two prominent areas in Boston where the buying and selling of human lives at auction took place.7 Both these sites were located in the heart of the city’s bustling commercial center, however many other, smaller-scale such transactions took place all over the city, including taverns, private residences, businesses, and on board ships.

Training

Tailors were some of the earliest artisans to settle in the British North American colonies.8 The presence of tailors in late 17th century Boston included Joseph Billings (1668/9-1748). He is the first documented generation of the Billings tailoring dynasty, and the father of Richard Billings, who placed the ad seeking the return of Exeter. The earliest direct evidence of enslaved men working in the Boston tailoring trade found thus far dates on January 26, 1712, when Stephen Boutineau placed an ad declaring “A Negro Man Aged about 16 years and speaks good English … has learned the Taylor’s Trade, to be Sold …”9

Enslaved men began their servitude laboring for tailors between the ages of 12 and 17. Training may have occurred side-by-side with formal, white apprentices, who began their training at the same age. Experience in the trade arguably made the sale of these enslaved men more profitable.10 In June 1751 an unnamed, 25-year-old enslaved man was sold at James Smith’s Sugar House along with “goods” including candy and molasses. The man was described as “fit for the Sea, or a Taylor’s Business;” a descriptor which may suggest this man had previously worked on a ship, perhaps employed making or mending sailors’ clothing or sails.11

A skilled tailor needed to be able to work with a variety of materials and embellishments. The cut and drape of the individual pattern pieces needed to be smooth, and seams stitched by apprentices strong, for an overall correct “look” to many different kinds of finished garments. While master tailors and their journeymen usually performed the more skilled and specialized tasks in a shop, such as measuring clients, and arranging the pattern pieces of a garment onto the fabric, and cutting them out, less skilled labor including enslaved men and white apprentices heated irons, stocked the shop and maintained its working order, performed errands, and delivered goods. Less skilled sewing work could include the repetitive stitching to secure seams on rectilinear pattern pieces making up garments such as shirts or trousers [Figure 2].

Documentation of the specific skills of enslaved men in the trade is scarce. An unnamed enslaved man, “very fit for a Taylor,” was recorded as possessing the knowledge to “work in Leather very well, having been used to the Needle for above a Dozen Years.” No evidence has come to light regarding enslaved men reaching the equivalent of master tailor status. In all likelihood, they never did so in any official capacity, for reasons including suppression by competing white members of the profession, as well as a lack of opportunity.12 Through years of unpaid work, however, some enslaved men may have reached an equivalent competency in the trade. The sale of the “Likely, healthy Negro Fellow” who “work’d at the Taylor’s Trade seven years” suggests the unnamed enslaved man clocked the same amount of time that a white apprentice would have to become a journeyman in the profession in the more formal guild systems of England and Europe.13 In short, it was probably on an individual basis how much and what kinds of work given enslaved man was able to do while held by a tailor.

The Appearance of Slavery

Enslaved men in Boston and greater New England could also be customers of tailors. An August 1779 tailoring receipt recorded garments made for men and boys in the family of Ebenezer Hancock (1741-1819) that included “making a coat and waistcoat for Cato” for 7 pounds, ten shillings.14 The fact that Cato’s clothes cost more than either of the two “sutes” for Ebenezer’s 10-year-old son Thomas (b.1769) may suggest that Cato was a domestic servant, an enslaved person working in the Hancock household or in regular contact with the Hancock family. Livery worn by such enslaved men, signaling both their servitude and the prosperity of the family holding them, could include the addition of applied, loop-piled worsted trim, or in rare cases, metallic braid or trim added to coats and waistcoats.15 Of course, most enslaved individuals did not wear livery, and most of the clothing they wore was far less ornate, cheaper clothing options to accommodate outdoor, physical labor. [Figure 3]. Leather breeches are connected to several enslaved men researched for this project, because of their hard-wearing qualities. Boston tailor Henry Lawson alerted white readers of an escaped man he held in the summer of 1725.16 The young man, whose name was Jemmy, wore leather breeches in addition to a dark frieze jacket and leather heeled shoes. Middletown, Connecticut, tailor Jehosaphat Starr, who could count among his customers young Jeremiah Wadsworth, also made at least three pairs of leather breeches for enslaved men, along with making or altering vests and coats, in the third quarter of the 18th century.17

Conclusion

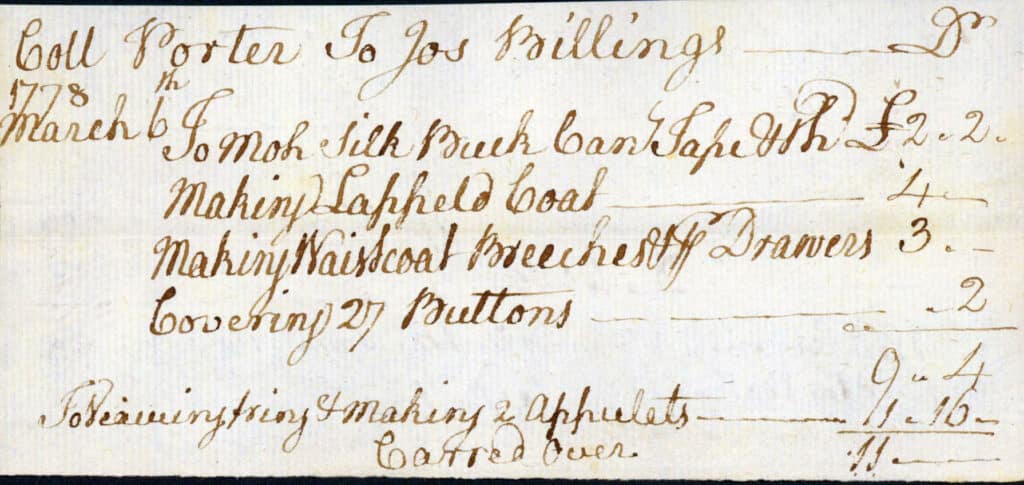

Figure 4. Receipt, Joseph Billings to Col. Elisha Porter, Boston, Massachusetts, 1778. Paper, ink. Historic Deerfield Library.

Exeter, the man cited at the beginning of this article, was in fact one of four enslaved men collectively held captive by the partnership of John and Richard Billings. These four men were all listed among the property and real estate at the time of the dissolution of the brothers’ business in 1763. The first names of all four men were listed with a corresponding “value;” Exeter (£20); Ceazer (£53.6.8); Cuff (£33.6.8); and Cato (£46.13.4). Exeter’s is the lowest of the four enslaved men, a fact which may suggest some circumstance, such as advanced age, that limited the amount of work he could perform, twenty years after his attempted runaway in 1741.

[Figure 4] In Historic Deerfield’s collection is a surviving receipt from Joseph Billings (1732-1789) for the making of uniform clothing for Hadley, Massachusetts, Colonel Elisha Porter in 1778. Remarkably, [Figure 5] the receipt includes these surviving epaulets. While no enslaved men are directly tied to Joseph, if we attribute at least part of the collective Billings family’s success, including real estate and goods, to the enslaved labor they held earlier in the century, these epaulets—and the work of other tailors—take on new meanings.

Resources:

- New England Weekly Journal, August 11, 1741: 2. Exeter was possibly the man baptized “as an adult” at Christ Church on January 19, 1736/7. See American Ancestors, “Inhabitants and Estates of the Town of Boston, 1630-1822 (Thwing Collection): p.7834.

- Jacqueline Barbara Carr, “A Change ‘As Remarkable as the Revolution Itself’: Boston’s Demographics, 1780-1800.” The New England Quarterly, Vol. 73, No. 4 (Dec. 2000); 584. G.B. Warden, “Inequality and Instability in Eighteenth-Century Boston: A Reappraisal,” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol. 6 No. 4 (Spring 1976): 593. Cite “Boston: Descriptions of Eighteenth-Century Boston before the Revolution.” National Humanities Center Resource Toolbox, Becoming American: The British Atlantic Colonies, 1690-1763, 2009. nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/, accessed September 1, 2018.

- Jacqueline Barbara Carr, “A Change ‘As Remarkable as the Revolution Itself’: Boston’s Demographics, 1780-1800.” The New England Quarterly, Vol. 73, No. 4 (Dec. 2000); 590.

- In 1738, the Marblehead, Massachusetts, built ship Desiré arrived with African slaves from the Bahama Islands. A year before, Samuel Maverick reportedly held at least three men of African descent on Noddles Island in Boston Harbor. See Robert C. Hayden, African-Americans in Boston: More Than 350 Years. Boston: Trustees of the Boston Public Library, 1992:15.

- In 1641, Massachusetts Bay Colony (along with Plymouth Bay) formally legislated the slave trade, and three years later (1644) Boston merchants expanded their capture and transportation of enslaved men, women, and children from the West Indies to trade for human lives directly in Africa. Hayden, 15.

- Robert E. Desrochers, Jr. “Slave-for-Sale Advertisements and Slavery in Massachusetts, 1704-1781.” The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. LIX (59), No. 3 (July 2002): 654-656.]

- Peter Benes, “Slavery in Boston Households, 1647-1770.” Slavery/Antislavery in New England: The Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife 2003 Annual Proceedings. Boston: Boston University, 2005: 16.

- Katherine Egner Gruber notes that a tailor named William Love was among the first settlers to the 1607 Virginia Company expedition to Jamestown. Another six tailors came to that settlement the following year. See “By Measures Taken of Men: Clothing the Classes in William Carlin’s Alexandria 1763-1782.” Early American Studies Vol. 13 No. 4 (Fall 2015): 934.

- The Boston News-Letter, January 26, 1712: 2.

- See Jared Ross Hardesty, “Laboring Lives,” in Unfreedom: Slavery and Dependence in Eighteenth-Century Boston. New York: New York University Press, 2016: 104-135.

- The BOSTON Weekly News-Letter, June 13, 1751; 2.

- Hostilities of white artisans directed against enslaved competitors was noted by John Adams in 1795. See Lorenzo Johnston Greene, The Negro in Colonial New England, New York: Atheneum, 1971: 113.

- The Boston News-Letter, November 24, 1757: 2.

- Rebecca Smith to Ebenezer Hancock, Dr, August 6, 1779. Hancock Family Papers, Series III (1739-1831), Bills 1779-1780, Baker Library, Harvard University.

- For information on livery worn by enslaved men in 18th-century Virginia, see Kruber, 944-945.

- THE New-England Courant, June 14, 1725: 2. Frieze was a coarse, napped woolen cloth suitable for colder weather. See Florence Montgomery with a foreword by Linda Eaton, Textiles in America, 16501850. New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 2007: 243.

- Jehosephat Starr account book, Connecticut Historical Society, MS 76564.

Related posts: