by Melody Amsel-Arieli

Rare Brussels silk Point de Gaze net lace wedding cape with applied decorations, 1840s, photo: Rubylane.com

Faded doilies and lacy gloves may evoke visions of bygone afternoon teas in overstuffed parlors. Yet these openwork textiles were likely inspired by highly embroidered Italian Renaissance church vestments.

In time, decorative needle lace—hundreds of impossibly tiny, twisted, looped, knotted, and plaited hand-worked needle stitches forming delicate, openwork fabric—followed. During the 16th century, needlecraft was considered a virtuous, ladylike pursuit. So, aristocratic girls and women spent much of their time adorning linens, samplers, undergarments, handkerchiefs, gloves, cuffs, and caps with elegant silver, gold, or silk needle lace edgings.

They also hand-stitched frothy lace sleeves, cuffs, petticoats, ribbons, jackets, and wide, flat collars. Though few of these historic garments have survived intact, fragments may be seen in select museums.

Yet exquisite needle lace garments do appear in prestigious portraits of this time. Members of the European aristocracy, for instance, often posed in elaborately folded, starch-stiffened needle lace ruffs. These expansive, costly creations not only symbolized the wearer’s social position and wealth but ensured perfect posture. However, by the late 1660s, wrote diarist Samuel Pepys, these cumbersome collars had been replaced by lacy rectangles tied comfortably at the neck.

As the love of lush needle lace swept Italy and France, young girls in convents spent years plying this craft. In time, a variety of types and patterns arose, reflecting a range of tastes and creative traditions. Many are named for their place of origin.

Venetian needle lace, for example, features scrolled floral patterns embellished with high-relief florals. Burano lace, originating on an island near Venice, was produced through its hallmark “punto in aria (“stitch in air”) technique—creating intricate designs onto themselves—without the use of briefly attached supportive cloth. In addition to imitating popular European patterns, Burano lacemakers created original designs worked in characteristic light rown cotton thread.

Needle lace fabric, produced in Alençon, France, features small, graceful roundels, buttonhole bars, and opulent picot edging, while Argentan lace, produced in nearby Normandy, features notably denser designs. Brussels needle lace, a flowery, shaded pattern known as Point de Gaze, features countless minute stitches worked in continuous threads against gauzy-mesh connective grounds. This fine, airy fabric appeared in fanciful fans, flounces, bridal capes, shawls, dresses, and parasols.

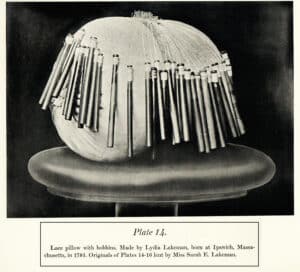

In addition to needle lace, Brussels a simpler, softer, less expensive pieces using whittled, weighted, thread-bearing wooden bobbins. Bobbin lace, also known as pillow lace, is readily created by crossing and looping threads pinned to pricking-card patterns attached to round, supportive pillows. As lace-trimmed tablecloths, lappets, linens, caps, coverlets, undergarments, and collars became increasingly trendy, bobbin lacemaking centers arose in almshouses, convents, and charity schools across Europe. Their names, like Lille, Chantilly, Cluny, Maltese, Bruges, and Bayeux, also reveal their points of origin.

Dutch and British American colonists evidently wore imported lace caps, collars, ruffs, and lace-trimmed aprons, dresses, and handkerchiefs as early as the mid-1600s. Yet acquiring these luxuries just before and during the Revolutionary War could be difficult logistically and politically. As a result, enterprising Colonial women wove, bartered, and sold profitable bobbin lace themselves.

There was a single commercial handmade bobbin lacemaking industry that arose in 18th century America in Ipswich, Massachusetts. Some believe that their handmade patterns arrived with immigrants from the British Midlands. Others, noting their resemblance to various types of European bobbin lace, believe French Huguenot refugees introduced them. In time, however, Ipswich lace makers developed patterns and characteristics of their own. Their “continuous lace” trimmings, adorning garments, and household linens, for instance, featured motifs, grounds, and fillings worked in continuous linen or silk threads from start to finish. According to surviving account books, Ipswich lacemakers marketed their opulent products as far away as Maine.

Since needle and bobbin lace was so exacting an art, both Colonial and European women dreamed of duplicating it on simple weaving looms. Yet all initial attempts failed. Only in the following century, with the advent of specialized lacemaking machines, did huge quantities of cheap, manufactured lace fabric flood the market. As a result, fabric merchants marketed handmade needle and bobbin lace as “real” lace.

Victorian women were especially charmed by lace. So in addition to natural and manmade wonders from far and wide, London’s 1851 Great Exhibition featured lacy creations both ordinary and odd. Malta, for instance, flaunted lacy “Greek style” toilet covers, while Van Diemen’s Land (modern-day Tasmania) unveiled an unidentified piece of “thread lace, made by a girl eleven years of age …”

Scottish needle lace curtains, cloaks, collars, gloves, hosiery, and ribbons lay beside Irish bobbin lace doilies, frocks, and lace-edged handkerchiefs and tablecloths. English merchants offered everything from an unidentified “specimen of lace made by a poor woman in Stone, Aylesbury” to elegant lace livery with matching patterns for carriage interiors. Since plunging necklines were the height of womanly fashion, many also offered scores of needle and bobbin lace Bertha collars – flat, cloak-like coverups named for “Bertha Broadfoot,” Charlemagne’s reputedly modest mother. Yet many featured stunning ribbons, feathers, sequins, crystals, pearls, or precious jewel embellishments. Moreover, beneath their corseted hourglass silhouettes, Victorian women sometimes favored alluring, lace-trimmed petticoats or camisoles.

Above all, explains Anna Halley, owner of The Highland Lace Company based in Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia, lace signified romance. “In Victorian times, the ardent suitor would send a pair of lace gloves to his beloved as a proposal of marriage. The young lady would then demurely signal her acceptance by wearing the gloves to a social engagement or church. Had she been undecided, she wore but one, signaling to her gentleman that the wooing should be continued.” Once wooed and won, brides wed wearing festive lacy gowns, veils, capes, and trains.

After World War I, Belgian and Venetian lace, typically gracing table runners and trimmings, grew bolder in design. By the mid-century, American machine-made Battenburg tape-lace, enhanced with hand-sewn needle lace fillings, edged an untold number of household linens and women’s garments.

Through the years, lacy and lace-trimmed fabrics like these were tucked away in hope chests and bureau drawers, then largely forgotten. Today, however, collectors and devotees are bringing these treasures, tangible links to women of the past, to life.

Lace-edged sheets and coverlets, for instance, can serve as attractive curtains, bedspreads, or tablecloths. Frayed, stained, or yellowed portions, trimmed away, can be fashioned into shawls, skirts, or sashes. Moreover, lacy bits and bobs, salvaged at yard sales, estate sales, flea markets, thrift shops, or antique stores, can be transformed into attractive shelf edgings, lamp shades, baby quilts, pillows, evening bags, or wall-hung ornaments under glass.

Vintage lace fabrics, dating from the past generation or so, are not only the most plentiful but the least costly. Many, depending on their design, size, purpose, and condition, can be found for under a hundred dollars. Sets of stunning, antique lace cuffs, collars, ties, and veil fragments—some over a hundred years old—may also be surprisingly inexpensive. In 2015, for example, Bonhams auctioned a collection of 18th and 19th-century lace, including Genoese, Gros Point, Milanese, Brussels, Mechlin, Devon, Binche, and Alençon fragments, for $376.

Fabulous antique lace fabrics continue to reach the market, explains Ms. Halley. “It is amazing what is coming out in all directions recently! There are lace auctions in Paris and the USA about once a year. And Instagram is a really great place to find old, unusual treasures!”

Related posts: