By Melody Amsel-Arieli

Handkerchiefs, also known as hankies, are thin, hemmed cloths carried in purse or pocket. They serve not only hygienic purposes, but also as decorative accessories. Vintage handkerchiefs, whether lacy confections, sturdy cotton florals, or designer works of art, reflect not only changing tastes, but also our cultural heritage.

Wealthy ancient Egyptians, for example, carried fine, embroidered squares of costly cotton or bleached linen. The Chinese blocked the sun and mopped their brows with small pieces of cloth. Wealthy Greeks apparently used perfumed linen squares, known as perspirator cloths, to mask body odor.

The earliest Roman handkerchiefs, linen squares imported from Greece, Egypt, and Spain, were called sudarium (from the Latin “to sweat.) As linen became less costly, the lower classes, too, began using them to wipe their hands and dress wounds. By 250 AD, handkerchiefs were ceremonial as well. Coliseum games began at the drop of a handkerchief and emperors awarded them to high-ranking officials. When gladiators faced death, spectators waved silk or linen handkerchiefs to signal their release.

From around 500 AD, Catholic clergy used fine, handkerchief-like linen bands to wipe their perspiration, and by the 12th century, draped them ceremoniously over their left arms. During the Middle Ages, knights carried damsels’ handkerchiefs, symbols of favor, as they left for battle.

In the late 1300s, King Richard II of England apparently introduced the handkerchief as we know it, by wiping his nose with squares of cloth. Though the French wiped their noses with mouchoirs (from the French for mucus), they dabbed away tears with fine cambric pleuvoirs (French for rain, tear, or cry). When mouchoirs reached England toward 1400, they were called mokadors, muckiters, muckenders, and muckinders. These unadorned cloths, suspended at mothers’ waists, caught sniffles, stifled sneezes, and wiped runny noses. Eventually, they became known as hand covers, then hand coverchiefs.

The Dutch, however, seem far more practical. Erasmus, a priest, social critic, and teacher, supposedly observed, “to wipe your nose on your cap or your sleeve is boorish…. to blow your nose in your hand and then, as if by chance, wipe it on your clothes, shows not much better manners. But to receive the secretion of your nose in your handkerchief, at the same time turning slightly away from persons of rank is a highly respectable matter.”

Throughout the Tudor era, silk, lawn, and fine linen handkerchiefs, featuring rich cutwork, metallic threadwork, lace, or pearls, were popular with men and women alike. Held in hand, they facilitated flirting. Tucked into sleeves, draped across arms, or peeking out from sweet bags, they demonstrated wealth and social status. Henry VIII, for example, owned dozens of handkerchiefs edged in Flanders needle lace, wildly expensive Venetian needlework, and trimmed in silver and gold.

Queen Elizabeth owned scores of handmade silk, cambric, and Holland cloth (dull-finish linen) handkerchiefs as well. She much preferred those stitched in colorful silk threads, however, or those worked in luxurious blackwork or whitework embroidery. Lavish pieces like these were so valuable, so valued, that they often appeared in dowry lists and wills. Despite their long, illustrious provenance, a surprising number have survived. Most are in private collections or museums.

England’s upper classes, in addition to acquiring handkerchiefs for themselves, sent tiny tasseled squares to lovers and mistresses as tokens of their affection. By the mid-1600s, lower classes also gifted suitors and sealed courtships with embroidered, perfumed pieces.

A number of intricately engraved, printed silk handkerchiefs were introduced in the 1650s. Some of these foldable pieces were politically oriented, commemorating British battles and royal speeches. Some feature convenient, textual travel aids like road maps and lists of coach fares. Others offer useful maxims or directions for soldiers. Extremely detailed, single-color copperplate engraved handkerchiefs appeared the following century. Some portray mythological tales, fashionable chinoiserie motifs, or pastoral panoramas. Some celebrate historical events like the American War of Independence. Others feature spiral-designed games or puzzles designed to test participants’ knowledge of history. Bright, intricately colored, popular hand-blocked cotton tie-dye and silk handkerchiefs also arrived from India, Bengal, and Pakistan. Few of these, however, have survived.

Handkerchief use increased as the use of snuff spread through England. Since decorous removal of unsightly, expelled tobacco was a sign of a gentleman, dark ones proved most suitable. Until now, handkerchiefs had come in different shapes. According to legend, however, when Marie-Antoinette declared a square to be the most aesthetic shape of all, her husband, Louis XVI of France, ruled that henceforth all handkerchiefs be equal in length and width. Since then, most are.

Industrial Revolution inventions, like the Spinning Mule, Flying Shuttle, and rapid roller printing, streamlined the entire British textile industry. Luxurious, handmade handkerchiefs were replaced by inexpensive, machine-made ones in an assortment of materials and patterns. By 1800, handkerchiefs had become so common that they inspired childrens games like Blindman’s Buff and A Tisket-A-Tasket.

Following the death of Prince Albert in 1861, etiquette required widows to observe extended periods of mourning. Many accessorized their dark “widow’s weeds” with black handkerchiefs. Then, as mourning progressed from stage to stage, these were sometimes exchanged for white handkerchiefs bordered in black.

Men initially concealed simple cotton handkerchiefs, those in actual use, in their trouser pockets. When two-piece suits came into fashion, however, these squares became personal forms of expression. In addition to those they kept hidden, many displayed elegant linen, cotton, or silk squares in their left breast pockets. Women, too, saved their best, white lace-edged, monogrammed, or embroidered hankies to complement special attire.

Though Kleenex was introduced in the 1930s with the slogan “Don’t Carry a Cold in Your Pocket,” cloth handkerchiefs remained popular through the 1960s. After all, handy handkerchiefs, twisted, knotted, or folded, could also tote bundles, buff shoes, clean tools, and perform other countless tasks.

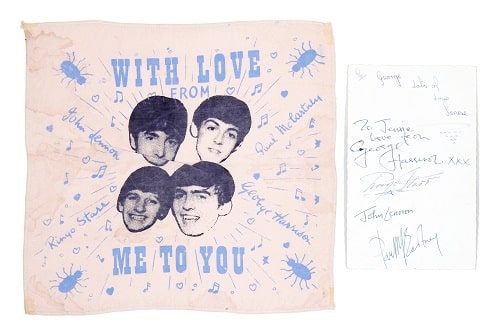

Because everyone tucked inexpensive, machine made ones in purses and pockets, they were often custom printed with advertisements for everything from Cocoa Cola and Kellogg’s Toasted Corn Flakes to Absolut Vodka. Many handkerchiefs marked celebrations, centennials, and world fairs. Others, portraying hotels, maps, state flowers, or historic landmarks, for example, served as lightweight, inexpensive souvenirs.

Today, as in Tudor times, handkerchiefs have once again become high fashion. Vogue Magazine, for example, has highlighted a variety of Burmel and Kimball designer hankies in its “Handkerchief of the Month” feature. Christian Dior, Pierre Balmain, and Rochas have accessorized their haute couture creations with one-of-a-kind, signed pieces. Fashion houses, like Hermes and Fendi, currently market exclusive, handmade handkerchief works of art in a variety of shades, shapes, and materials.

Some collectors favor particular themes, like animals, advertising, or animated art characters. Some seek simple, machine-made cotton ones featuring geometric prints, florals, or bits of embroidery. Some prefer monogrammed handkerchiefs that, with a bit of sleuthing, may reveal entire family histories. Others collect rare, vintage, hand-embroidered or lacy confections, with proven provenance, in prime condition. Handkerchiefs, big or small, simple or sumptuous, can be found at estate sales, antique stores, flea markets, and thrift shops. Because they command from one to a thousand dollars, there is a handkerchief for every pocket.

Melody Amsel-Arieli, an Israeli-American raised among collections of antique telephones, Stangl pitchers, pop-up books, and Native American jewelry, writes extensively about collectibles and history. She is the author of Between Galicia and Hungary: The Jews of Stropkov (Avotaynu) and Jewish Lives: Britain 1750-1950 (Pen & Sword). Visit her at www.amselbird.com.

Related posts: