by Melody Amsel-Arieli

Samplers are pieces of fabric worked to demonstrate mastery of ornamental embroidery stitches and motifs. This fine art arose in the late Middle Ages when English nuns and needlework professionals created exquisite, gold and silver-gilt embroidered ecclesiastical and secular textiles. From about 1350, however, their quality declined. Materials became less lavish, techniques became less complex, and appliquéd motifs replaced allover designs.

Ornamental needlework flourished anew from around 1534, when Henry VIII, on dissolving ties with the Catholic Church, appropriated its luxurious, embroidered chasubles, copes, and altar hangings, as his own. As this elaborate style became fashionable at court, men and women, professionals and amateurs alike, adorned vests, sleeves, gowns, handkerchiefs, pockets, pin pillows, linens, and table carpets with arrays of colorful embroidered stitchery. Their craft was not simply a pleasant pastime, however. Due to the exorbitant cost of fine linen and silk thread, it also indicated wealth and social status.

Spreading Design

With the expansion of international trade, exotic silk and metallic threads from faraway lands, as well as embroidered garments, reached English shores. These were not only highly fashionable but greatly admired. If a particularly attractive Hungarian pattern, say, caught a needlewoman’s eye, she might deftly work a sample across a long, narrow linen band kept rolled, like a diploma, in her sewing basket.

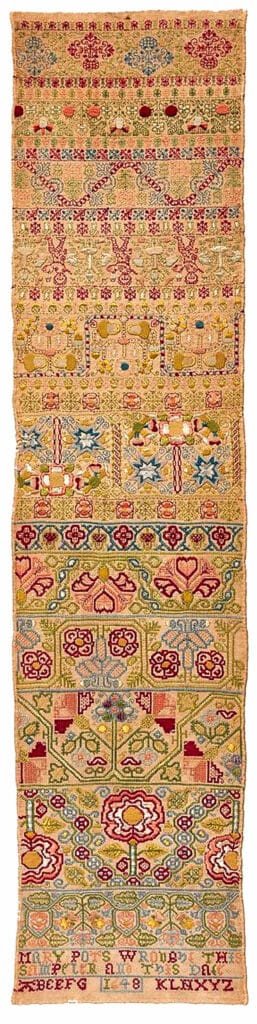

Over time, dizzying arrays of Holbein, Florentine, satin, cross, couched, bouillon, spider web, and Ceylon patterns covered every available inch—often worked in green, blue, and salmon. Later, when embellishing needle cases, shoes, gloves, stomachers, and the like, women sourced these bands for ideas and inspiration.

Skill Development

Since they also shared prized patterns and stitches among themselves, these band samplers, as they became known, continued to evolve throughout their lifetimes – and longer still. Some, included in household inventories, were apparently willed from mother to daughter. Though surviving examples are rarely signed or dated, they are more than a compendium of popular 16th century stitches. Each preserves their creators’ personal preferences for posterity.

As amateur needlewomen became more proficient at their art, some commissioned elaborate motifs from professional workshop draftsmen. Others copied or adapted designs depicted in rare, expensive German, French, English, or Italian printed pattern books. Since plagiarism was common, however, identical floral and geometric designs appeared time and again across Europe.

Other embroiderers, inspired by woodcuts and engravings in Tudor emblem books, bestiaries, and herbals, scattered flora and fauna motifs at random over linen foundations. Since some appear incomplete – and were rarely signed, many believe that these spot samplers, like band samplers, were created for reference. Others wonder if they were stitched as practice before attempting costly needlework projects. In any case, many consider them the liveliest, most vivid, imaginative samplers ever created.

Trends & Expansion

Although samplers appeared in British household records from 1502, the earliest known surviving one was worked by Jane Bostock in 1598. In addition to squares of complex geometrical and floral repeating patterns, it depicts a randomly placed owl in a tree, a chained and muzzled bear, a crouching hind, a number of dogs, a spray of cowslips, and a heraldic lion, symbol of strength and courage. Most are worked in silk cross stitch enhanced with seed pearls and beads. In addition, observes the Victoria and Albert Museum of Art and Design Internet site, three motifs, appearing to be “a castle on an elephant, a squirrel cracking a nut, and a raven,” have been “unpicked.” Could unpicking stitches have been a teaching tool?

Through the 1600s, band samplers, though still worked horizontally, incorporated increasingly complex techniques and sophisticated designs. Stump work, for example, featured raised, padded, pictorial motifs. Cut-and-drawn threadwork featured background linen threads which, when carefully cut away, revealed intricate, multi-colored patterns beneath. And there was a dizzying choice of stitches.

For Tent-worke, Raisd-worke, Laid worke, Frost-worke, net-worke,

Most curious Purles, or rare Italian cut-worke,

Fine Ferne-stitch, Fisher stitch, Irish-stitch, and Queen-stitch,

The Spanish-stitch, Kesemary-stitch, and Mowse-stitch,

The smarting-Whip-stitch, Back-stitch, and the Cros-stitch.

All these [stitches] are good, and these we must allow,

And these are every where in practice now.

– from The Needle’s Excellency, John Taylor, 1631

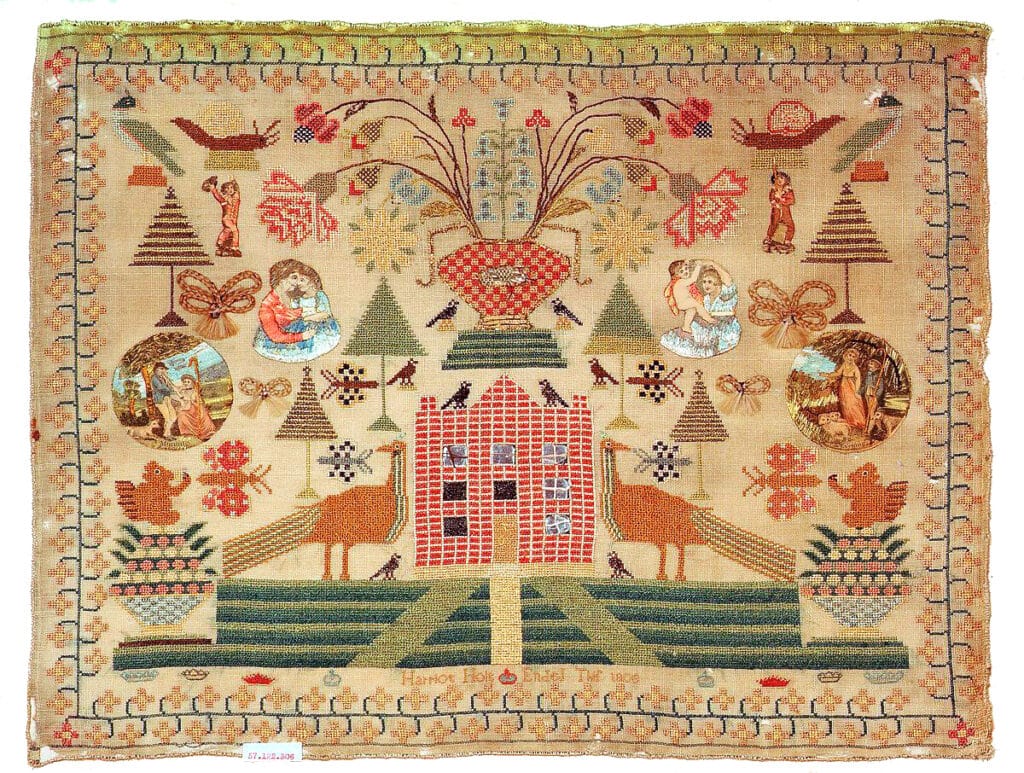

By the 1700s, samplers had become shorter, symmetrical, and more stylized.

In addition to alphabets, repeating patterns, and scrolled, vined borders, many accommodated lush pastoral visions of grazing sheep, stags, and does frolicking beneath budding trees—and rarely, outlandish images of Bedouin tents or flocks of camels. Unlike earlier, practical, rolled samplers, these were unique works of art, displayed like portraits and paintings.

Because households commonly marked their linens with embroidered initials or numerals, sampler work also became an integral part of an English schoolgirl’s education. In addition to simply worked, central, or bordering alphabets, many depict a charming bird, fruit, flower, thistle, peas-in-a-pod, or cherub-like “boxer” motifs, evoking Italian Renaissance putti.

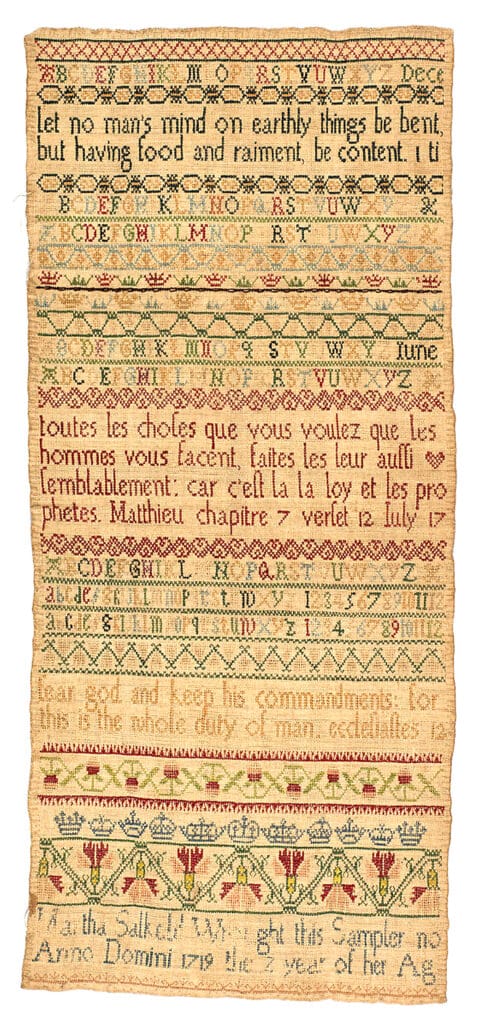

Through this era, many samplers also featured inspirational verses pondering life or extolling piety, duty, or feminine virtue. In 1719, for example, Martha Salkeld, in addition to multiple alphabets, decorative bands, and verse from the Book of Matthew and Ecclesiastes, cross-stitched

“let no man’s mind on earthly things be bent

but having food and raiment be content”

By mid-century, many samplers also depicted mansion motifs personalized with images of local sights, family members and beloved pets. Others commemorated christenings, weddings, or deaths. Yet to family researchers, genealogical samplers, whether matching names to relevant dates or burdening leafy trees with factual abundance, may be the most valuable of all.

Skills as Necessity

Schoolgirls also stitched almanac chart, mathematics table, and geographic linen samplers. Though their outlines of Wales or the world, for instance, might be none-too- accurate, these taught them the basic lay of the land.

Through the 1800s, household servants were required to mark linens with embroidered numbers or initials. So girls in asylums and charity schools stitched practical samplers to prove their marking, mending, and sewing skills. Students at the Bristol, England orphanage stitched particularly dense creations, with multiple rows of alphabets, numerals, and border patterns worked in red or black cotton thread. Though to some, these appear identical, additions of biblical motifs, moral verses, groups of initials (possibly of fellow students), and the occasional image of a small, single elephant, distinguish one from the next.

Because British stitchery was so popular, a relatively large number of samplers, tucked away in trunks, chests, or beneath the eaves of old garrets, have survived intact.

Students attending Colonial American “dame schools,” some as young as six, struggled to coax crude woolen thread into simple cross stitches across homespun, a fabric more suited to youthful hands than linen. So their samplers often featured uneven corners, lopsided images, and crooked borders. Spelling errors were common as well. Furthermore, some pieces were left at loose ends – unfinished.

Since schoolmarms often favored particular motifs, chose designs, sketched them, then supervised their creation, there was little room left for girlish imagination. As a result, all samplers from a particular school, in Newport, Rhode Island, or Newburyport, Massachusetts for example, might exhibit identical stitchery and content. Seen as a whole, they illuminate the lives of early American schoolgirls. Studied individually, however, they may reveal local customs, mores, as well as personal family histories.

Pennsylvania’s Westtown Quaker School, like its British counterparts, also embraced the sampler tradition. Very plain, practical marking and alphabet samplers were most common. Yet from the early 1800s, many students, like eleven-year-old Rebecca Marsh, rendered restrained, distinctive designs, featuring symmetrical floral spot motifs and classmates’ initials, with admirable precision. In fact, these Quaker school graduates became some of the best needlewomen of the 19th century. Since American samplers are far rarer than English ones, they are generally more valuable. Since most were made along the Atlantic Seaboard and throughout New England, those from Southern states are most collectible.

Around 1850, as the craze for garish Berlin wool work and canvas needlework, combined with the advent of machine-made products, the age of samplers drew to a close.

What To Look For

American and English samplers dating from the 1600s are generally held in private collections or museums. Later ones, however, still surface in flea markets, antique stores, at auction, and in estate sales.

A sampler’s age, however, may be less critical than its condition, detail, and design.

Vibrantly hued, pictorial ones are more collectible, for example, than those featuring simple numbers or alphabets, even if they are intricately stitched. Clear, charming, recognizable motifs—especially ones that are unusual—also add value. So does stitching that reveals the age and name of their creators, along with their locations and dates of completion. Samplers that feature personalized inscriptions are particularly endearing. And a having personal connection to a sampler, of course, enhances its value in the eyes of its beholder.

Though many consider undated, anonymous samplers less desirable, their styles and designs, if researched at local libraries, genealogical, and historic societies, may reveal their origins.

Moreover, peeks at their reverse sides may, through their degrees of neatness and quality of stitches, offer tantalizing hints about their creators. These too give voice to lives once lived.

Related posts: