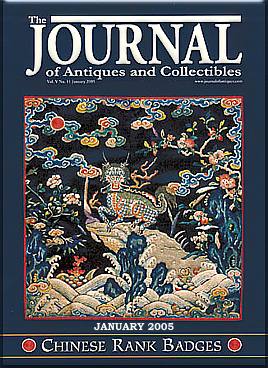

Chinese Rank Badges – The Journal of Antiques and Collectibles – January 2005

Important men in China during the Ming and Qing dynasties didn’t need printed calling cards to explain their rank. They wore it in splendid color, gold thread and pattern on their chests and backs. They wore it in the form of mandarin rank badges, achieved through many years of intensive study and horrendous examinations.

These badges have become coveted collector’s items. However, it is not the first time around for this. During the late 19th and early 20th century, the badges were prized collector items for wives of western diplomats stationed in Peking or Shanghai, and missionaries throughout China. It is thanks to these collectors that we are able to find many of the badges that come available today. The western collectors in old China not only framed the beautiful badges and hung them on walls, thus preserving them for future generations, but made evening purses of them. They put them under glass-covered serving trays, made decorative boxes adorned by them, and other imaginative items. They were most innovative with the regal badges that had been displayed with great pride by mandarin on the black silk surcoats worn over the colorful dragon robes on all official occasions in the court of the last emperors and empresses of China.

Two groups of men achieved badges, civil and military. Each category had nine ranks. The civil rank badges feature birds for identification, and the military utilize animals, both real and mythological. There were also special badges for men called Censors, a group of appointed officials who conducted special investigations for the emperor and served to identify wrongdoing and inefficiency among members of the general bureaucracy.

From the day a male child was born, it was the parent’s dream that he study for and pass the examinations, thus achieving rank and the right to wear the designated badge. This brought fame to the family, and frequently positions that led to great wealth. A boy who passed an examination, upon returning to his home village, was hailed as a hero. Of the ten thousand or more in a particular region who went through the killer examination ordeal, approximately 100 passed.

Wealthy families might start boys preparing for the exams as young as three years old. Quite naturally it was the wealthiest boys who succeeded since they had the advantage of fine education. However, a poor boy who was bright and found a way to study for the exams definitely stood an equal chance. Through the centuries the studies for the exams did not vary. The education was in reality a memorization marathon, with few students really understanding what they were learning.

The old formal Chinese learning process was based almost exclusively on noisy repetition. First, the master introduced a small selection of characters (of which there are many thousands of characters) to the class. Then his pupils were expected to recite each character after him, first in a normal speaking tone, then over and over again at a shout. Following this process, the boys learned the sound of each character, but seldom had any real knowledge of what it meant.

After they had memorized at least a thousand characters they began to learn the classics. Their first book was The Character Classics. When this was memorized exactly as it was written, no personal interpretations allowed, they progressed to The Analects of Confucius, The Book of Rites and The Book of Changes. Confucian thought was the basis of a boy’s education from the beginning. General topics such as math, science, geography, history were never part of the curriculum. One important result of this education based on the past, not the present, was that it did not produce free-thinking young intellectuals who might rebel against the system.

The first civil examination was generally taken at approximately age 18. Those who passed were awarded the Flower of Talent or Hsiu-ts’ai title and were entitled to wear the ninth rank badge, the Paradise Flycatcher. This would be equivalent to receiving our Bachelor of Arts degree.

They would then proceed to the second degree examination. Success here meant the title of Chu-jen or Promoted Scholar had been achieved. This title was comparable to the western Master’s Degree. Those who became eligible for the third examination traveled to Peking where it was taken in the Forbidden City under the jurisdiction of the emperor of China. Passing this was a tremendous accomplishment and generally meant great future success. The title Chung-yuan or Laureate was received. This honor is beyond any Western degree.

The examinations were taken in cell-like rooms situated side by side along narrow streets inside a vast compound in cities throughout China. In the city of Canton the examination hall consisted of 11,673 of these cell-rooms which were open in front, five feet, six inches long by three feet, eight inches wide and with very low ceilings. They were furnished with two wooden planks, one was a seat and the other functioned as a writing table. If a student wanted to rest a bit, he lowered the table plank and placed it parallel with the seat to form a sleeping platform.

Meals were provided by the emperor. Bathroom facilities consisted of a container in each cell or a trip to the public latrine at the end of each street of cells. Once the candidates were closed into the examination compound, the gates were locked. They had to remain inside. There were no exceptions – not for medical reasons, not for death. Should the examiners decide it was necessary to remove a dead body to prevent contagion, a hole was cut in one of the exterior walls and the body was carried through. The examiners went to tremendous lengths to prevent cheating.

There was enormous pride in passing these examinations. Great numbers took them and few passed. But once a boy passed all three civil examinations he rose rapidly to power positions in China in most cases. The governors of provinces, viceroys and other top officials close to the emperor were chosen from the third group.

Military examinations were not handled in the same manner. They were based on physical tests, not intellectual. It was swordsmanship, archery, and handling of horses that were important here. Consequently, military rank was not looked upon with the same respect as intellectual civil rank.

Civil Rank Badges

| 1st Rank | Crane | Recognized by a red cap on head |

| 2nd Rank | Golden Pheasant | Recognized by two tail feathers |

| 3rd Rank | Peacock | Recognized by elaborate tail feathers |

| 4th Rank | Wild Goose | Recognized by black marks like comas |

| 5th Rank | Silver Pheasant | Recognized by five tail feathers |

| 6th Rank | Egret | Legs appear in variety of colors |

| 7th Rank | Mandarin Duck | Recognized by blue tail |

| 8th Rank | Quail | Recognized by dumpy shape and scales |

| 9th Rank | Paradise Flycatcher | Recognized by two long tail feathers with single circle in each |

Military Badges

| 1st Rank | Chi-lin, a mythological animal |

| 2nd Rank | Lion |

| 3rd Rank | Leopard |

| 4th Rank | Tiger |

| 5th Rank | Bear |

| 6th Rank | Panther Cat |

| 7th Rank | Rhinoceros |

| 8th Rank | Rhinoceros |

| 9th Rank | Sea Horse |

The badges are generally 11 inches square, although sometimes you will find them 12 inches square. And occasionally you come across small pairs of badges made for the eldest son of a proud father, the insignia being the father’s rank. These came in late in the Qing dynasty when rules about costume became very relaxed.

The badges weren’t restricted to men, although they are the ones who earned them. Wives were also entitled to wear badges of their husbands’ rank on black surcoats for official occasions. The way to distinguish the women’s badges from the men’s is the placement of the red sun disk, generally thought of as representing the emperor of China, that is found on all badges, civil and military. The man’s sun disk was always placed in the upper left hand corner of the badge. Since the wife frequently sat next to her husband on official occasions, her badge was made in mirror vision of her husbands and the sun disk on her badge was in the upper right hand corner. This way her bird or animal was respectfully facing her husband’s.

Men always bought their own badges which were made by workshops specializing in the creation of rank badges made in an assortment of techniques. Embroidery on dark silk background was one of the most frequently found techniques. A variety of stitches were used. The finest embroidered badges incorporated perfect satin and other needle stitches, and frequently utilized the tiny French knots known as Peking Knot that was mistakenly often called the “forbidden stitch.” While it was very hard on the eyes to do this fine work, the stitch was never officially forbidden, and it is being done again today on better copies being sold as antique. There are rare examples of beautiful embroidered badges where real seed pearls have been incorporated in the design of white birds such as cranes or egrets. And threads spun from the green barbs detached from peacock feathers were worked into others giving an iridescent green glow. Badges with the peacock feather remaining are rare as there is a small mite that evidently loved feasting on peacock feather threads.

Couching is another technique utilized on embroidered examples of badges. This consists of using silk threads covered in gold or silver foil laid down side by side, then caught in place by tiny stitches of silk thread. To get unusual effects, these stitches might be in a contrasting color, for instance in using red, the gold would appear to be more copper color.

Lovely examples of multi-color brocade badges can be found. And at the end of the Qing dynasty, possibly as an economic measure knowing the badges would not be worn much longer, an inexpensive brocade type of badge was produced in black and white, with red sun disk, or gold color and black with red sun disk.

Counted canvas stitch or what the French call petit-point was used on gauze fabric for summer robes. Another form of this type of work was the Florentine or flame stitch which the Chinese called “gauze-stabbing.”

The most expensive badges the collector will find will be executed in the k’ossu or kesi weave. Because of the difficult process of executing the k’ossu weave, these are not being copied as prolifically today. The basic explanation of k’ossu weaving is: plain colored warp threads and various continuous colored silk weft threads follow a painted pattern. Shuttles of weft threads weave one small single color section of the design, which is then ended. The next small section is done in the same way and ended. In working this way, a slit is created at the end point of each color, giving an overall effect of being carved silk or engraved thread. K’ossu work, if unlined, will show this very clearly when held up to light.

The beginning collector will find they are more likely to come across high rank badges than the lowest rank badges in both civil and military. One reason for this is the men of first rank could afford many badges if he wished, whereas the holders of lower ranks were not in the same financial position.

It will also be easier to find civil badges than military. When the Republican revolution overthrew the imperial system in 1911, military men had great reason to destroy their badges. It was frequently a life-saving measure to not have their past so easily identifiable. Conversely, the Confucian scholars with civil rank were frequently incorporated into the new Republican government. They had no need to destroy their identifying badges.

Before going any further I must warn new collectors of mandarin rank badges to beware of newly manufactured badges. The “antique” stores of mainland China, Hong Kong, Singapore, as well as some stores in the USA and London are filled with brand new badges being sold as very old. Some dealers go so far as to advertise their badges are Ming. It is fairly safe to say that 95% of badges currently being offered for sale on eBay are brand new, no matter what the sellers might claim. And frequently the copies are quite marvelous and can fool all, but the most expert, long-time collector.

One thing to be alert to in buying badges is the smell of smoke. This doesn’t mean the mandarin who wore the badge left his surcoat lying around near the fireplace. It means the badge has been smoked to artificially age it.

The discussion of fakes brings us to the question where does the collector look for the real thing. Estate sales are one very good place. While there is happy hunting in seaport cities like Boston and Seattle where the China Trade was heavy, you can also have good luck in towns anywhere in America. The reason for this is missionaries. There were very large numbers of American missionaries of all denominations from all over the USA working in China during the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century. And the flat badges were easy packable souvenirs for them to bring home. Elderly relatives who inherited these badges die and their children and grandchildren have no interest in them. So they are put for sale.

Flea markets and garage sales are other places to look for the same reasons as the estate sales. Small antique stores that aren’t too chic, can sometimes have rank badges hidden away. And of course, if you want to go about collecting seriously and spend some serious money, Asia Week in New York in March always offers very fine examples of rank badges for sale, as does the Arts of Pacific Asia antique sale in San Francisco every November and their Los Angeles sale in the spring. Asia Week in London in November is another place to find really fine badges. Buying from a top dealer, you are generally sure of getting a genuine old badge. But you won’t be getting bargain prices.

Resources for More Information

One good thing to do is locate a museum in your area where badges are on display and study them carefully. Training the eye is important. Also, reading detailed descriptions of the badges and the various techniques incorporated in making them can be a great help to you. The following are some books I recommend for reading and research:

- Finlay, John R. “Chinese Embroidered Mandarin Squares from the Schyler V. R. Cammann Collection” Orientations Vol. 25, no. 9 (September 1994) pages 56-63

- Garrett, Valery M. [amazon_link id=”0195852397″ target=”_blank” container=”” container_class=”” ]Mandarin Squares Hong Kong[/amazon_link]: Oxford University Press, 1999

- Jackson, Beverley and Hugus, David [amazon_link id=”1580081274″ target=”_blank” container=”” container_class=”” ]Ladder to the Clouds: Intrigue and Tradition in Chinese Rank[/amazon_link] Ten Speed Press 2002

- Rutherford, Judith “Manchu Badges of Rank” Australian Collectors Quarterly (May/June/July 1992) pages 52-7

- Vollmer, John E. [amazon_link id=”1580083072″ target=”_blank” container=”” container_class=”” ]Ruling From The Dragon Throne[/amazon_link] Ten Speed Press 2003

- White, Julia M. and Bunker, Emma C. [amazon_link id=”9623210388″ target=”_blank” container=”” container_class=”” ]Adornment for Eternity: Status and Rank in Chinese Ornament[/amazon_link] Marquant Books 1994

And any articles or books you might be able to locate by the late Schuyler Cammann.

My Grandfather was a missionary doctor in China 100 years or so ago…the women still bound their feet( I have 2 pr of shoes). I also have 2 mandarin squares-male & female, some kind of a cat, maybe a tiger or a leopard? Trying to find out values…I also have prayer wheel & a doll that you change heads, not clothes. I am in Omaha NE, any idea where I could take these to be appraised?

Dea Lisa, do you havé photo of your items?

If it were me, I would contact Christies, or Bonham and Butterfields auction houses. Or, a local Asian Museum can give a good reference for both appraisal and restoration work if needed. Good Luck!