by Judy Gonyeau,managing editor

photo: George Washington’s Mount Vernon

The English immigrants who came ashore in the 1600s brought their acumen with them, including a taste for British goods when it came to the household and the clothing they wore. It has been said the Native Americans loved to sell their worn-out beaver fur to the English because they were done with it, while the immigrants sent it back to England to be made into proper hats and the like. That was a win-win for both sides.

Now, fast-forward to the later 1700s as the American Revolution was winding down. Having relied on England to supply everything from equipment to cloth to tea, the view of a post-connected country also meant severe restrictions on imports, including the coveted quality wool made in England. Now, America was having to create resources of its own to have those things it wanted in its new society.

Wool in a Post-Revolutionary America

In a new, but war-ravaged, country, resources for building the American society had been torn through for the sake of liberty. Animal stock was in low supply and the Founding Fathers were taking on the role of Founding Farmers to help establish what resources would become the staples of this new land.

Sheep had a very low population as they had been killed to feed the troops (on both sides) and even those that were of the type that made for the best mutton and the best wool were gone. Now, the country had to rebuild its stock to populate the field and make cloth. Not just any cloth, but fine wool to dress the new leaders and elite of the country.

According to The American Wool Industry 1789-1815, the Hartford Woolen Manufactory was established as an early attempt at making wool broadcloth for the American public. They supplied George Washington with 13 1/2 yards of brown wool used to construct the suit he wore for his inauguration. As Washington said to the Marquis de Lafayette, “I hope it will not be a great

while before it will be unfashionable for a gentleman to appear in any other dress. Indeed we have already been too long subject to British prejudices.”

A brown wool suit that belonged to George Washington is in the Mount Vernon collection, although this may not be the suit he wore to his inauguration as he had a few made by the same company over time. Mrs.Washington was praised for her dress made of “fine Hartford brown Cloth” that she wore for the trip to New York for the inauguration.

The consistency of wool produced by the Hartford Manufactory was not consistent due to the lack of quality wool being raised in the country during this time, and the inability to import sheep from abroad. The company closed just eight years after it opened.

Smaller makers began to pop up across New England and along the coastline. Yet, the quality of American wool remained at the root of the issue surrounding quality. Pennsylvania farmer Richard Peters wrote to George Washington, stating that “For some time hence this will not be a great sheep country. … As to fleece it is but scant pounds per sheep being rather an over calculation. Wool is now in some demand but I have known it unsaleable. I hope manufactures will continue to increase demand but the prospect of this is distant. … I know none who have tried the sheep business and succeeded.”

Washington became vested in this matter, growing his stock of sheep from 200 in 1797 to 800 in 1788, while investing in a Persian ram to improve the overall quality of the wool being harvested. Thomas Jefferson invested in Tunis sheep (although not the same as Tunis sheep today) and a quality Shetland ram, and invested in Tunis brought here from North Africa and East Asia. Others followed in their tracks by breeding with better quality rams, but they lacked the one thing people were pining for: Merino wool.

Make Mine Merino

While importing sheep into this new country was difficult at best, the DuPont family brought over the first imported sheep named Don Pedro from Spain in 1801 and began his foray into the wool industry. In 1802, Col. David Humphreys also imported 100 merinos, 25 rams, and 75 ewes from France. Then, in 1810, Spain exported 20,000 merinos to the U.S. because Spain needed the money and America needed the sheep.

The looming War of 1812 cut the U.S. out of trade with Great Britain once again, and the wool from the sheep was once again being somewhat depleted by war. After the war ended, cheap fine wool was once again available from England because there was now a surplus of merino.

The ups and downs of supply and demand were taking their toll. It was time for America to have its own wool industry with refined quality.

America, Let the Industrial Revolution Begin

An American breed or sheep was being further defined by breeding ewes to the Tunis (“Barbary sheep”) rams, and also to merino sheep helped bring about a more refined wool. George Washington’s stepson George Washington Parke Curtis played a role in promoting American wool and proper breeding after he “discovered a flock of feral sheep on Smith Island that were said to have wool as fine as any merino. Custis crossed the Smith Island sheep with his Persian ram and another longwool ram named “Bakewell” (not to be confused with the Bakewell breed of sheep, also known as Leicester Longwool) and created the Arlington Improved breed.” (The American Wool Industry) From there, he started annual sheep-shearing contests, and over the course of a few years, it was still the Merino that won the day.

This all brought focus to the building of the American sheep that had originally come across the ocean, much like the farmers who raised them. Inventions leading to a greater vision of processing wool and other fabrics brought about the Industrial Revolution as it was applied to the textile industry.

Mills were popping up across the country, and with each new mill came new towns and cities surrounding them and providing the labor needed to work the machinery. As machinery continued to improve, the sizes of the mills grew exponentially, and a small mecca for manufacturing fine wool appeared in Lowell, Massachusetts. As the demand for high-quality wool continued, employment numbers climbed, and the number of people needed to fill the jobs climbed. By the mid-1800s, the mills turned to hiring women from near and far to fill the vacancies, showing this opportunity to be more of a delightful adventure where women could bond while working side-by-side.

This One’s for the Girls

The story depicted here is about a young girl who relinquishes her middle class life and identity to experience life as a working mill girl, fancying that this will grant her a “freer life.”

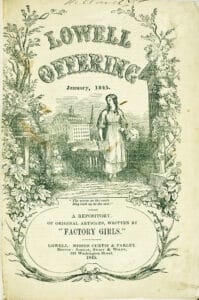

She ultimately meets and falls in love with a young boy whom she believes to be a cottage hand but is, indeed, a rich gentleman. The story, like the image, provides an example of how mill girls were frequently romanticized in literature directed at the middle class. photo: American Antiquarian

Selling the idea of allowing women to join the workforce of factories was a marketing “ploy,” saying it was all about financial independence and joining together with other women (and girls – some discovered to be as young as 10) in a community of happiness and support. Little did many of the young girls selected to work in the mills know that they were about to enter the world of the sweatshop filled with 12 to 14-hour workdays, pay constrictions, and tight, communal living arrangements where there were at least two, but more likely three to a bed.

The typical prized recruit was a “farmer’s daughter” who was between 14 and 35 years of age looking to help pay for her brother’s college tuition, help the family with bills, take part in the lectures and programs available to them from the factory, or sometimes acquire a little financial independence. Often, the girls would recruit friends or members of their families to join them to make life a bit less lonely.

Not Your Average “Dickens Factory”

Both boarding houses and the educational opportunities that were offered to the employees were thanks to Francis Cabot Lowell who was looking to distance the conditions there from the Charles Dickens’ take on factory life in books such as Oliver Twist of David Copperfield, or from Dickens’ own life when he was forced at the age of 12 to work at a boot black factory in order to help pay off his father’s debts.

Lowell invited Dickens to come and visit his woolen factories after which Dickens noted that the Mill Girls were “well-dressed” and wore “serviceable bonnets, good warm cloaks, and shawls.” He also remarked the women were “healthy in appearance and had the manners and deportment of young women, not of degrading brutes.” Dickens was also pleased by the Mill Girls’ high level of literacy, especially in The Lowell Offering, a published journal.

However, this was just a portion of his four-month trip to the U.S. His resulting work from this trip, called American Notes, is “infamous for its criticisms of America and Americans, but less noted is the fact that Dickens found America’s factories laudable in many respects, including the treatment of workers.”

Who Were the Mill Girls?

This article provides us with not only a firsthand account of a mill but also how it would have appeared to an outsider, anticipating his or her

reactions. It captures the pace of work, the immense size yet cramped conditions of the mill, the varied kinds of work conducted on each floor, and the women’s exhaustion at the end

of the day. While Baker praises the opportunities

for self-improvement,

such as lectures or classes, she bemoans the lack

of time available for

such pursuits.

photo:

americanantiquarian.org

Of the thousands of women working in the mills at that time, most were girls who left the family farm. According to The Worcester Journal, “74% of the workforce in the Hamilton Manufacturing Company was female, native-born, and their average age was 24.

“The residents were strongly encouraged to read, learn, and worship regularly, no matter what their denomination. Popular literary choices included novels, newspapers, bibles, and periodicals, and many of these works were provided by a lending library for a small fee. These books would be the basis of learning for many of the women working in the mills.”

Mill Girls were paid half of the rate paid to men, $3-$4 per week, and from that, they had to pay room and board (75¢ to $1.25) and were provided with three square meals a day. Each “house” had a widow or a couple who would run a strict lifestyle that included a 10 p.m. curfew and mandatory church attendance for all the girls.

As their numbers grew, the women formed book clubs and published their own journal, The Lowell Offering, where they would share stories about life at the mills.

On the factory floor, there were typically two men to oversee the work of 80 women as they worked through the day from 5 a.m. to 7 p.m. By 1840, Francis Lowell’s associates were expanding the mills to the point that they had 8,000 employees, and the nickname “City of Spindles” was attributed to the city of Lowell. By 1860, the number of spindles in the city had jumped from 2.25 million to 5.25 million, and the number of workers jumped to 122,000.

Organizing Women: The Foundation for Women’s Rights

Who were all these workers supplying goods for? It could be said for the investors, who were reaping a great return of 14% per year. The corporations were raking in high profits as well. And yet the women working in the factories were going through pay cut after pay cut in order for the company to keep upgrading their equipment and still take a profit.

At the same time, another publication had gained traction – The Voice of Industry. Here, the story of a good life at the woolen mills was presented in a different way. One of the employees named Juliana put it this way, “[There is a] very pretty picture, but we who work in the factory know the sober reality to be quite another thing altogether.” The 12-14 hour days left little room for partaking in the educational classes and left women so exhausted it became difficult to keep up their own lifestyle as well as those they supported. The room and board did not change despite paying a lower wage. Another worker described her living quarters as “a small,

comfortless, half-ventilated apartment containing some half a dozen occupants.”

Over the years, The Offering also shared stories of labor unrest in the factories, and an article on Mill Girls’ suicides.

Timeline of Organized Labor and Strikes

In the early 1830s, the Board of Directors proposed reducing the wages for women. When they suggested a 15% reduction in pay, the Mill Girls would meet to discuss their situation. In February 1834, they produced a run on the area banks as they withdrew their savings and organized their first strike. While the strike failed and the workers either went back to work or left town, some people felt the strike was a “betrayal of femininity.”

Later, in January 1836, the company’s Board indicated they wanted to increase the price of rent to offset the economic calamity caused by the boarding of housekeepers. In October, they wanted yet another rent hike. Protests were rampant and the girls formed the Factory Girls’ Association and organized another strike.

Harriet Hanson Robenson was just 11 and working as a doffer when the strike occurred. In her memoir she wrote, “One of the girls stood on a pump and gave vent to the feelings of her companions in a neat speech, declaring that it was their duty to resist all attempts at cutting down the wages. This was the first time a woman had spoken in public in Lowell, and the event caused surprise and consternation among her audience.”

In 1845, the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association (LFLRA) was formed as the first union of women workers. Membership swelled to over 500 in just six months and continued to expand.

This was an all-female organization, run for and run by women for the betterment of working conditions at the mills. Those who

were elected to officiate the Union also worked with other women working in other mill towns, setting up branches of the LFLRA that all contributed insight and assistance to the organization.

First up for the LFLRA was to secure enough signatures on petitions given to the corporation demanding a 10-hour work day. The Massachusetts Legislature formed a committee with Lowell Representative William Schouler as its leader. The committee’s charge was to investigate and hold public hearings where testimony would be taken from workers regarding the length and impact of the regular workday on their work and lives. These were the first investigations into labor conditions made by a governmental body in the U.S.

The result of the investigation was that they felt the State had no business controlling the number of hours employees would work. In response, The LFLRA called its chairman, William Schouler, a “tool” and worked to defeat him in his next campaign for the State Legislature. In a complex election, Schouler lost to another Whig candidate over the issue of railroads. The impact of working men [Democrats] and working women [non-voting] was very limited. The next year Schouler was re-elected to the State Legislature.

Despite having lost the request for a shorter workday, the LFLRA continued to expand and became affiliated with the New England Workingmen’s Association. They continued to contribute to the Voice of Industry newspaper while maintaining pressure on the mill owners to lower the length of the workday. In 1847, mill owners reduced the workday by 30 minutes. That same year, New Hampshire passed a law for a ten-hour workday. Unfortunately, the law was not enforceable.

By 1848, the LFLRA dissolved. Workers continued to pressure management for better working conditions and in 1853, the Lowell Corporation reduced the workday to 11 hours.

Mid-Century Upheaval

As the woolen industry continued to grow and the quality of the American sheep’s wool improved, demand was now outnumbering supply. Wool was being imported from around the world, and the West was beginning to be a more important supplier to the industry.

Yankee ingenuity took off as improvements to machinery continued to improve production numbers, but unrest between the North and South eventually choked the supply of cotton from the South to be finished in the North and eventually, mills shuttered their doors.

By the Civil War, woolen manufacturers in New England registered numerous patents to keep their machine and wool processing inventions in the North, leaving the South without the ability to replicate the more refined finishing techniques so easily as wartime approached. At this point, New England mills created much of the blue uniform cloth worn by the Union Army. These mills continued to thrive into the 20th century until the use of synthetic fabrics became all the fashion. The South was left with too much cotton and nowhere to turn for finishing cotton fabric and making money for the Confederates.

What Was It All For?

According to the AFL-CIO, what did the LFLRA do for women working in factories? “In the short term, not much. That’s how it often is with the first pioneers in social justice movements. Both of their strikes were crushed. And the only victory they won in their 10-hour workday campaign was pretty hollow.

In 1847, New Hampshire became the first state to pass a 10-hour workday law – but it wasn’t enforceable.

“That was in the short term. But in the long term, the Lowell mill girls started something that transformed this country. No one told them how to do it. But they showed that working women didn’t have to put up with injustice in the workplace. They got fed up, joined together, supported each other, and fought for what they knew was right.”

Or, as said by a Mill Girl, “They have at last learnt the lesson which a bitter experience teaches, not to those who style themselves their ‘natural protectors’ are they to look for the needful help, but to the strong and resolute of their own sex.”

Today, millions of women in unions who teach our kids, fight our fires, build our homes, and nurse us back to health owe a debt to the Lowell mill girls. They taught America a powerful lesson about ordinary women doing extraordinary things.

Related posts: