by Grant Geissman

By the spring of 1952, artist/writer/editor Harvey Kurtzman was exhausted from researching, writing, laying out, drawing for, and editing the world’s first true-to-life war comics, Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat. For these, Kurtzman would do meticulous and time-consuming research, including talking to war veterans, reading historical accounts, and even going up on a test flight. The final product was stunning, if only moderately successful.

Truth was, in spite of all his hard work Kurtzman simply wasn’t making enough to support his family. He appealed to EC Comics publisher Bill Gaines for a raise, but payments were calculated by the number of books an editor could turn out, not by the time it took to do one. Gaines proposed a solution: If Harvey could sandwich in another book between the ones he was already doing (a book that could be done quickly, without all the heavy research), his income would go up by 50 percent. What kind of book might that be? Kurtzman was good with humor, so why not try that? Thus, out of a simple (yet pressing) need for more income, MAD, a publication destined to become an American institution, was born.

THE BEGINNING

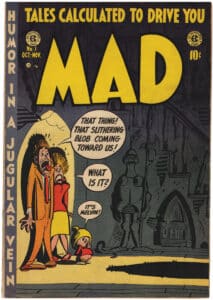

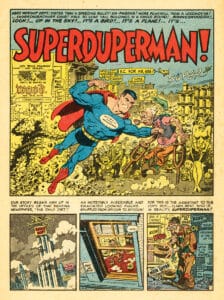

The first issue of MAD, a 10¢ comic book, was cover-dated Oct.-Nov., 1952, and appeared on the nation’s newsstands in August. The initial concept was to satirize the kinds of comic books that EC had been turning out: horror, science fiction, crime, and even EC’s very short-lived romance comics. The artists selected for MAD were the same core group of artists who had been working on Kurtzman’s war books: Bill Elder, John Severin, Jack Davis, and Wallace Wood. The stories, while comedic, were nonetheless aimed at an older, more sophisticated reader than was the average “funny book.” The first few issues found Kurtzman trying to find the book’s focus, but with the fourth issue, he struck comedy gold with “Superduperman,” the fledgling publication’s first bona fide classic. MAD had found its voice, satirizing not just generic comic book styles, but specific comic book and comic strip features. And little by little Kurtzman began taking on movies, television, politics, and various other aspects of popular culture. MAD had become a hit, selling upwards of a million copies of a 10¢ comic book.

By 1955, MAD had been a comic book for nearly three years, but for all of MAD’s success, Kurtzman was still not satisfied. Harvey felt he was slumming in the world of comics, and he longed to break into the world of magazines. Kurtzman had been entertaining a job offer from Pageant magazine, and he told Gaines he was thinking of leaving. To keep Kurtzman in the fold, Gaines offered to let him re-invent MAD as a 25¢ magazine, an offer Harvey readily accepted.

The first magazine issue (No. 24, July 1955) flew off the newsstands, prompting a second printing, which is all but unheard-of in magazine publishing. Despite the success of the new MAD, there were still problems, most notably that the perfectionist Kurtzman just couldn’t stay ahead of his deadlines. And he was demanding more money—not for himself, but to spend on the magazine. Harvey’s deadline problems and demands did not endear him to MAD’s publisher. The formerly friendly Gaines/Kurtzman relationship became increasingly strained.

THE BREAK-UP

After producing five issues of the magazine, Kurtzman found that he had a not-so-secret admirer in the young Hugh Hefner, who had recently launched Playboy. With a standing offer from Hefner, Kurtzman went to Gaines and demanded 51 percent ownership of MAD, a demand Kurtzman almost certainly knew Gaines would not meet. Gaines refused, and Kurtzman made his exit. Kurtzman and Hefner almost immediately began work on a lush, expensively produced new humor magazine called Trump. Gaines was distraught, convinced that without Kurtzman there could be no MAD. And worse, Kurtzman had taken with him most of MAD’s artists. With no other options, Gaines brought in his former right-hand man at EC Comics, Al Feldstein (who had been let go after the collapse of Gaines’s comic book empire) to take over as MAD’s editor.

Feldstein quickly picked up the pieces. “I don’t know how the first few issues got done,” Feldstein said, “but they got done. It was just one incident of serendipity after another. All these talented people were walking into the office, not aware that there’d been this terrible change—that Harvey had left and taken all the artists with him. I don’t think they knew that there was a new editor who was on his knees praying for artists and writers to help him do his job.” Artists answering his prayers, and who would soon become familiar names among MAD fans: Don Martin, George Woodbridge, Mort Drucker, Norman Mingo, Kelly Freas, Bob Clarke, and Dave Berg (with EC veterans Wallace Wood and Joe Orlando also contributing). The first new writer in the door was Frank Jacobs, joined a few years later by Arnie Kogen, Larry Siegel, Al Jaffee, and Dick DeBartolo.

The pragmatic, hard-working Feldstein got the magazine back on track and back on deadline. With a regular schedule and what was arguably a more accessible package, circulation—which had recently been slipping under Kurtzman—began to increase.

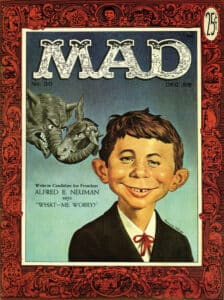

NEUMAN

Soon after Feldstein arrived at MAD, the impishly grinning “What—me worry?” face and the name “Alfred E. Neuman” were wedded once and for all, and Alfred became the magazine’s cover boy and mascot. Kurtzman had found the face, and appropriated it for the cover of the first MAD paperback book, The MAD Reader (published in 1954 by Ballantine Books). Kurtzman began to sprinkle “the face” around the magazine under various names. (The actual “first” appearance of the face has been determined to date back to at least the late 1800s, and was used to advertise everything from “painless dentistry” to 1940s anti-President Roosevelt sentiments.)

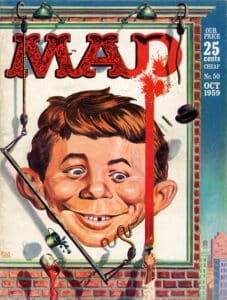

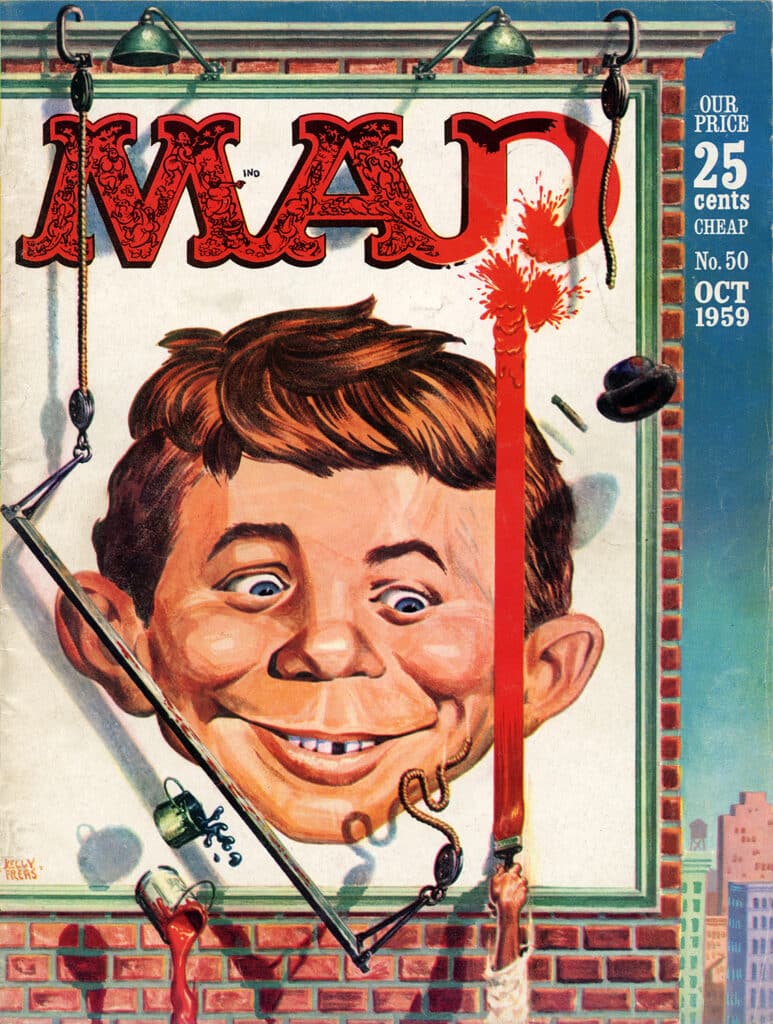

Feldstein had the image fleshed out in full color by illustrator Norman Mingo; Mingo’s Alfred ran for President on the cover of issue No. 30 (December 1956), and appeared enshrined on Mount Rushmore on the cover of the following issue. Alfred graced the cover of virtually every issue since.

Mingo departed after doing eight covers, and illustrator Kelly Freas began a long run of cover duties. Freas departed in 1962, and Mingo returned as the magazine’s premier cover artist, continuing until his death in 1980. Other notable MAD cover artists include Jack Rickard, Mort Drucker, Jack Davis, Al Jaffee, Bob Jones, Sam Viviano, James Warhola, Mark Fredrickson, and Richard Williams, who brought a classic, Norman Rockwell-styled approach which made him an instant favorite.

A NATIONAL TREASURE

By about 1958, MAD was again selling a million copies a month, and by the dawn of the 1960s, the magazine was regarded by many as a national treasure, and by some as a national disgrace. Gaines, after being vilified for his EC horror comics and abandoned by Harvey Kurtzman, had emerged triumphant. He began to reward his staffers and the freelances who had met a minimum yearly page count by taking them on lavish, all-expense-paid group trips to exotic locales. A large, gruff-but-affable man with a paternal nature, Gaines had an unusual policy regarding office deportment: as long as the work got done, the deadlines were met, and the magazine made money, he didn’t care how long the lunch hours were, about the staff punching a time clock, or about any certain code of dress.

Paradoxically, Gaines was also as cheap as he could be generous, and on one notorious occasion stopped work in the office for two days to track down a personal long-distance phone call no one would admit to. As a lark, he once filled up the office water cooler with wine and spent the day watching his staff get even nuttier than usual. “I create the atmosphere, the staff creates the magazine,” said Gaines, in perfect summation. By the early 1970s, Bill Gaines had come to be regarded as one of the world’s great eccentrics, and by the time of his death in 1992, he had—along with the magazine he published—become a full-blown American cultural icon.

GROOVY, AND BEYOND

While Kurtzman originated the format, MAD’s most popular features of the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, and onward were developed under Feldstein’s editorship, including Dave Berg’s “Lighter Side,” Al Jaffee’s “Fold-Ins,” Mort Drucker’s movie parody caricatures, Sergio Aragonés’s “MAD Marginals,” and Antonio Prohias’s “SPY vs SPY.” The MAD message, almost from its inception, was not to believe everything you see, that authority might need to be questioned sometimes, Madison Avenue is lying to you, and that absurdity abounds – a message that was not lost on its readers. MAD associate editor Nick Meglin always maintained, “MAD doesn’t really create as much as reflect. We hold a funhouse mirror up to life.” But that’s not the whole story.

Because the MAD staff produced a magazine that they themselves enjoyed, MAD’s humor had several layers. Having read MAD as a kid in the 1960s, I can vouch for the fact that some of the humor was aimed right down at our level where we could get at it, but, tantalizingly, much of it was a bit beyond us, which made the magazine all the more indispensable.

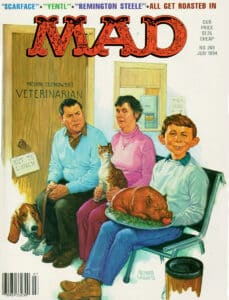

a number of artists have illustrated covers for MAD. One of the best is Richard Williams, who brought a Norman Rockwell esthetic to his work for MAD. Pictured here is his Rockwell-influenced cover to MAD

No. 248, July 1984

To us kids in the early sixties, MAD provided not just a funhouse mirror but also a two-way mirror into the real world, a world MAD-ly skewed, but one that would be unfathomable without MAD. What kept us buying the magazine (when the same money would have netted two comic books and a candy bar) was that MAD was a sort of first primer for adult life, a necessary ingredient, and manual for the rites of passage. When all was said and done, the really amazing thing about MAD was that it was a magazine for adults (with a readership that extended from us to high school, college, and far beyond), but we “got it” too, and the guy in the drug store didn’t look at you funny if you tried to buy a copy.

END OF AN ERA

After nearly thirty years of editing the magazine, editor Al Feldstein decided to retire at the end of 1984. Bill Gaines promoted longtime associate editor Nick Meglin (who had contributed many funny ideas to the magazine and had a proven eye for talent), and a relative new-comer to the editorial staff (and a former MAD freelance writer) John Ficarra to be co-editors. This proved to be quite a successful arrangement, which continued for nearly twenty years until Nick Meglin retired in 2004 after an incredible 48 years with the magazine.

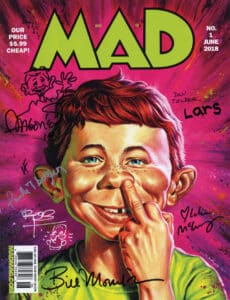

Ficarra carried the torch until December 2017, when MAD’s corporate owners announced that the office (which had always been based in New York) was moving to Burbank, California. None of the longtime staffers elected to leave New York, and a new editor, Bill Morrison, was anointed. A relaunch followed, starting over with a new MAD No. 1 (June 2018). After a very promising start, it was announced on February 4, 2019, that editor Morrison had been unceremoniously let go. Several months later, nearly all of the remaining staff was also released.

MAD will continue, but consist primarily of reprints, and be sold only in comic shops and via subscription. This is a decidedly unfunny fate for the publication that influenced so many generations of readers.

IT’S A WRAP?

Despite all the changes, MAD has been published continuously for nearly 70 years. For millions of people, the world would not be the same if their minds hadn’t been rotted by MAD, in either its comic book or magazine incarnation. Kurtzman’s MAD, for example, planted the seeds of anarchy in such future sixties underground comix cartoonists as Robert Crumb, Gilbert Shelton, Bill Griffith, and Rick Griffin, as well as in future Monty Python member/visionary film director Terry Gilliam. The Feldstein-edited version of MAD (and the later incarnations edited by Meglin and Ficarra) had an equally profound affect upon its readership as an indispensable rite of passage, a kind of primer into the ways of the world, even if satirically skewed by MAD’s “fun house mirror.”

It’s hard to say what the future holds for MAD, along with many publications that are actually printed on paper. But for those of us who grew up loving MAD, it’s hard to imagine a world without it.

Long Live the MAD-ness!

Guitarist/composer Grant Geissman has written several Eisner Award-nominated books about MAD and EC Comics, the most recent being The History of EC Comics, published by Taschen. He was nominated in 2004 for an Emmy Award for co-writing the theme to the CBS TV series Two and a Half Men.

Related posts: