Majolica Around the House

The Journal of Antiques and Collectibles – April 2007

By Jeffrey B. Snyder

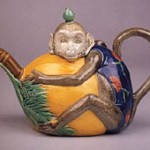

Majolica, that soft-bodied earthenware molded in low or high relief decoration and glazed with a startlingly broad palette of brilliant lead glaze colors, was first introduced to the general public by Herbert Minton at the Crystal Palace Exhibition of 1851 in London. Popular with the public for its ornamental forms and lively glazes, the enthusiastic production of majolica was quickly taken up by potting firms large and small in England, Continental Europe, and the United States. Majolica was at its height of popularity from the 1850s through the mid-1880s. By the late 1880s, majolica was generally overproduced and overall quality was on the decline. Majolica wares would continue to be made on into the twentieth century, mainly in Continental Europe and Australia, but the majolica appearing on the American market by that time was largely comprised of inexpensive premium items and carnival prizes.

From the 1850s through the early twentieth century, majolica wares were produced in such a wide variety of forms, from the thoroughly useful to the outrageously ornamental, that they could literally be placed in every room of a Victorian home. Majolica umbrella stands stood ready in the entryway; platters and oyster plates graced the dining room table; whimsical pitchers brightened cook’s day in the kitchen; bright tea sets served a family’s afternoon tea in the sitting room; manly humidors graced a gentleman’s study or billiard room; majolica figurines in human, mythological, and animal forms cavorted in whatnot cabinets in the parlor; spill vases resided on the mantles; desk sets shone brightly in the library or the boudoir; dressing and chamber sets were at home in the bedrooms; miniature tea sets, fanciful figurines, and amusing banks found use in the children’s rooms and nursery; and formidable jardinières on pedestals vied with the ornamental plants they held for the viewer’s attention in the conservatory … or anywhere else the soothing, green touch of nature was deemed appropriate.

While some early examples from the 1850s and 1860s were spectacular and expensive works of art, the vast majority of majolica wares were more affordable. In form and decoration, majolica wares reflected the many, shifting passions of the Victorian age. A potent combination of Victorian romanticism and naturalism provided the impetus for capturing much of the natural world in majolica ceramics. Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection also fueled the fascination with the natural world.

Entering the House

The nineteenth century simple shotgun house or modest town house was a three or four room affair with a dining room, parlor, and a bedroom or two. The largest Victorian homes were far grander affairs, complete with a variety of specialized public and private rooms, all of which had uses for majolica.

Private spaces were a family’s personal rooms (rooms where guests were not generally received), workrooms, and kitchens, including:

- Bedrooms: known as “chambers” in wealthy homes, the well to do also had “servant’s quarters”—bedrooms for the in-house staff.

- Boudoir: where the lady of the house wrote letters and attended to family business.

- Breakfast room/sitting room: well to do families took their breakfasts in a separate room from the dining room and this room doubled as a family’s informal living room, referred to as a “sitting room.”

- Library/study: where the man of the house wrote his correspondence and attended to business.

- Nursery/children’s rooms: separate bedrooms for the babies and growing children.

- Workrooms: where family members or servants labored.

The public spaces in a large Victorian house included:

- Entryway: the room that ushered guests into the house and set the tone of the home. In a large English Victorian townhouse, the dining room was on the ground floor off the entryway (at street level), the drawing room/parlor was up the staircase on the floor above. Larger, sprawling Victorian homes would have both rooms on the ground floor.

- Billiard-/Smoking-room: a gentleman’s domain.

- Conservatory: a green house used to bring nature and warmth into the Victorian home, especially useful and uplifting on a cold winter’s day.

- Dining room: where formal Victorian dinners were held, attended by many guests who were served numerous courses.

- Drawing room/parlor: the public room where guests were received, referred to as “salons” in wealthy homes, “parlors” in more modest abodes.

There are a number of Victorian majolica items that could be used in many rooms to add decorative touches or serve useful functions.

Public Places

Entryway

Victorian etiquette required gentlemen and ladies to leave their umbrellas and walking sticks in umbrella stands in the entryway when visiting. Large majolica umbrella stands glittering in the entryway were sure to make an impression on all who entered or exited through the front door.

Drawing room/parlor In the drawing room, where Victorian guests first gathered during an evening’s socializing, elegant majolica vases, match holders, and figurines could be found on the fireplace mantle, in the whatnot case, on top of built in bookshelves, in recessed alcoves, on tabletops, and hanging from the ceiling in the form of ornate chandeliers. Heavy drapes were employed in the drawing room to protect the carpets found there. Carpets and wallpaper became increasingly common in the homes of the affluent and rising middle class as the nineteenth century progressed. Brightly glazed majolica wares would stand out nicely in these ornate, dimly lit confines.

Activities moved from the drawing room to the dining room for a formal meal on many social outings.

Dining room

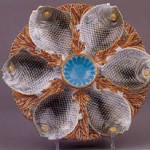

Display was an important aspect of any formal Victorian dinner. The formal dinner was an affair designed to impress ones guests and raise ones social, and possibly business, standing in the community. Impressive majolica tableware and centerpieces helped provide the proper impact. During the course of a formal dinner, majolica wares would be used to serve a variety of courses. Any serving pieces that did not receive heavy use from a knife and fork were produced in majolica. For a formal dinner for twelve, ten courses could be served prior to dessert, coffee, and walnuts.

Fruit and oysters in abundance were impressive on the Victorian table. New national railway systems and refrigerator cars allows what had once been exotic and seldom eaten delicacies to grace nineteenth century tables. Fruit was eaten with special knives and forks, never with the hands. Strawberries received their own special server, complete with sugar and cream containers. Strawberries were also served with afternoon teas. Oysters were favorites of every social class. However, an ostentatious display of oysters at a party using special majolica oyster servers and plates surely raised one’s status in the eyes of guests.

Major majolica serving pieces came and went from the table with each course. The impact these items made on the guests was fleeting. However, impressive centerpieces and small majolica wares remained and reinforced a positive lasting impression. These small pieces included butter pats and individual salts. Dessert services were designed to finish the impressive formal dinner with style. The service itself, lavishly decorated with tasteful flowers and fruit, consisted of low and high comports, at least two cake plates, and twelve dessert plates.

Billiard-/Smoking-room

Cigars were symbols of manly status and success for Victorians. After a formal meal, while ladies retired to the drawing room for tea or coffee and conversation, the men drank port and smoked cigars in the dining room … suggesting that humidors and smoking sets were not merely relegated to the billiard- and smoking-room. However, Victorian etiquette declared a gentleman must not smoke in front of a lady. Hence, the smoking-room was a man’s territory where he was free to indulge in a cigar without offending the ladies. A complete smoking set included an ashtray, cigar box, matchbox, spill case, and tobacco box. Complete sets in majolica are very difficult to find today.

Conservatory/porch/garden

As an expression of the nineteenth century passion for nature, Victorians constructed elaborate gardens, hothouses, and indoor conservatories. Nature, well manicured, was ushered into the Victorian home. To accommodate this trend, potteries produced a wide range of majolica garden accessories, from pedestaled jardinières and garden seats to elaborate planters, flower holders, flowerpots, cachepots, and wall pockets.

Victorians used these flowerpots, planters, and jardinières in and around their homes. Whether used in elegant conservatories or on humble windowsills and exterior staircases, decorative flowers and plants around the house were considered evidence of cultural refinement. If the pots and jardinières were beautiful objects, so much the better.

Flowers were also seen as morally uplifting in the Victorian era. A homemaker might place flowering plants prominently around the home in the hope of elevating the morals of those she lived with. Medicinal herbs were also grown by some in flowerpots and planters, not only for their decorative value, but also for their use in homeopathic remedies. Some viewed these medicinal herbs as a sign of God’s beneficence, providing natural cures for the children He loved and indirect evidence, through the cessation of pain, of an afterlife in which all pain is banished. When herbal remedies worked, they were perceived as a sign of God’s very existence.

Private Spaces

Bedroom

Majolica items that were most likely to be found in the Victorian bedroom include small boxes, trinket trays, powder boxes, candlesticks, ring stands and trays, match stands, and comb trays. Such items are rarely found today.

Majolica ewers and basins for washing were also produced. During the early Victorian era, a wash set in every bedroom was a sign of true civility.

Breakfast room/sitting room

Early in the nineteenth century, a breakfast set included twelve cups and saucers with larger teacups than were generally used for other occasions, a sugar bowl, milk pot, teapot, waste bowl, and breakfast plates. Larger sets added a coffee pot, butter boat, and cake plate. By the end of the nineteenth century, fruit and mush had been added to the breakfast menu, each requiring its own plate or bowl.

Having tea at five o’clock in the evening had become a popular Victorian ritual by the 1860s. Tea services for five o’clock tea included the teapot, sugar bowl, creamer, cups and saucers, cup plates, waste bowl, plates, two cake plates, preserve plates, butter plate, a tray, hot-water urn, spoon holder, and at times a syrup or molasses pitcher. If a lady so chose, breakfast and tea could be served on a rotating table in the boudoir.

The immediate family would have used majolica tea and breakfast wares. These colorful, whimsical items added a light touch to a family’s private moments. Formal silver services were produced when serving tea to guests.

Kitchen

The typical middle and upper class Victorian house might have as few as two or three servants in the house. These were the cook, housemaid, and parlormaid. If a family had children, a nursemaid was also required. Those households that managed with only two servants employed a cook and a “maid-of-all-work.” This household staff was comprised largely of young women in their early twenties who could read and write.

During archaeological investigations at the nineteenth century Laurier House in Ottawa, Canada, once owned by a well-to-do Victorian jeweler and his family, a wide variety of kitchen items were recovered, including baking dishes, pudding and mixing bowls, five teapots, and a majolica pitcher of a simple tree bark design. The majolica pitcher recovered was American made after the mid-1880s. The archaeologists felt the servants themselves would have used this inexpensive piece. It was believed to be too common to appear on the homeowner’s table; but, the staff, who ate their meals on plain white earthenware—the cheapest tableware available in Canada at that time—would have welcomed the bright colors.

As may be seen, Victorians had uses for majolica in all its forms throughout their homes. The glints of bright color and the fantastic forms of majolica arranged throughout your home are sure to impress today’s visitors as much as they did Victorian guests during the latter half of the nineteenth century.

[amazon_link id=”076432134X” target=”_blank” container=”” container_class=”” ]Antique Majolica Around the House[/amazon_link] By: Jeffrey B. SnyderPrice: $49.95

Publisher: Schiffer Publishing

610-593-1777

ISBN: 076432134X

From grand jardinières to diminutive butter pats, this book features ceramic majolica that added vibrant color to every room of the home in over 450 brilliant color photographs. Majolica wares are organized here by the rooms (library, conservatory, drawing room, boudoir …) in which they were used, including cake stands, comports, game pie dishes, oyster plates, platters, strawberry servers, tea sets, humidors, match holders, garden seats, umbrella stands, vases, and an elegant chandelier. The major manufacturers from Britain, Europe, and the United States, including Minton, George Jones, Sarreguemines, Wedgwood, and Griffen, Smith & Hill are all well represented.

A brief history of majolica, a detailed bibliography, and an index are included. Current market values are found in the captions.

Pingback: White House China - Rjanti Queattic