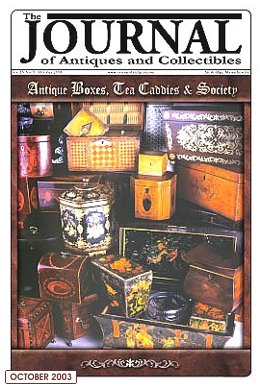

Antique Boxes, Tea Caddies, & Society – The Journal of Antiques and Collectibles – October 2003

Tea caddies or tea chests – the decorative boxes that contain canisters – epitomize a whole era of English society. It was the era of decorum, when social repartee attained a delicious peak of theatrical interaction. Tea was served ceremoniously, but not prudishly; it allowed for intrigue, scandal, business, intellectual exchange, and, perhaps most of all, style.

Containers of the precious tea leaves were objects of pride. Made by artist cabinetmakers, they reflected the stylistic and cultural developments of the 18th and 19th centuries as well as the idiosyncratic preferences of the commissioning clients. Lord Petersham, of snuff box fame, was one of the Regency-period dandies who elevated the art of affectation to exquisite refinement. He had a selection of tea caddies so he could store his tea leaves according to their character. I find this idea appealing because it gives collecting quirky angle. After all, collecting, which can open up avenues of knowledge and scholarship, must also be fun.

Tea itself was very expensive when it was introduced to Europe in the 17th century, and it continued to be so for nearly two centuries. The trade in tea and opium, which was pivotal to the fortunes of England, is dealt with in some detail in our book [amazon_link id=”0764316885″ target=”_blank” container=”” container_class=”” ]Antique Boxes, Tea Caddies, & Society 1700-1880[/amazon_link]. Suffice it to say here that during the 18th century, a pound of tea could be as much as a week’s pay for a skilled man. The aromatic leaves were kept under lock and key in beautifully constructed containers which reflected the status of the tea and of the household.

18th Century

The first tea chests were mostly made by English cabinet makers and date from about the second quarter of the 18th century. They are often rectangular and shaped like small trunks. They were made in mahogany, or sometimes walnut. These contained metal or wooden canisters. Tortoiseshell, or shagreen-covered examples housed silver caddies. Thomas Chippendale, in his book The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director 1754 (and its subsequent editions), published 12 designs of trunk-shaped tea chests, some with metal mounts and some with chinoiserie fretted carved decoration. Other makers, followed the same designs, mostly keeping to the less ornamented examples and the straight-sided forms. Bombe, concave, and serpentine shapes are rare.

The next significant design development came about with the spread of neo-Classicism during the last two decades of the 18th century. Tea chests were then made in straight lines with very discreet decoration, mostly in the form of central flat handles and fine stringing and cross-banding. The choice of woods, which was employed as thick saw-cut veneers, was extended to include other timbers such as yew, fruitwoods, satinwood, harewood, partridgewood, kingwood, and rosewood. The chests were made to a very high standard of workmanship, and although to the uninitiated eye they may look simple, they are in fact structured with meticulous attention to detail and aesthetic excellence.

At about this time, single caddies were made in some numbers. These were mostly inlaid, either directly into the veneer, or featured marquetry ovals, which were inserted into the center of the top or front, or both. Sometimes the inlay was enhanced with “engraving,” fine inked lines defining the detail of the design. Shell motifs, neoclassical abstractions, and stylized flora were the preferred decoration.

Unfortunately, because prices for caddies have soared over the last decade, there is now an epidemic of fake caddies on the market. Caddies are more vulnerable to faking than tea chests because the structure is simpler. Machine-made marquetry panels and prints are often obscured under new polish or varnish. Caution must be taken to ascertain the age of the surface. Newly-lined interiors, locks without internal workings, and the smell of wood stain are all giveaways. But, unfortunately, the fakers always seem to be one step ahead. Avoid flat, smooth, raw looking boxes. Sometimes the interior may look old, but the exterior has been re-veneered or enhanced. Also avoid gimmicks, such as different and complex shapes, unless you examine the item with great care. Remember the Georgians prided themselves for their sophisticated taste.

Tortoiseshell and ivory caddies of this period are subtle and restrained, making use of the quality of the material rather than complex shaping or decoration. These caddies are also fiercely faked. In addition to the danger of buying a fake, remember that the use of these materials, if new, is illegal. Unfortunately we have seen fakes and illustrations of fakes where they have no right to be. A deep understanding of the aesthetic criteria of the period will hopefully help avoid the pitfalls.

The late 18th century also saw the advent of the rolled paper, or “filigree” tea caddy. These delightful objects were decorated mostly by ladies at home or school, although some were made by professionals and by Napoleonic prisoners of war. The prisoners also made caddies decorated with straw work, a fine craft popularized during the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th centuries. A few straw work caddies were made by nuns and craftsmen in the 17th and earlier 18th centuries. These are extremely rare.

Caddies covered in vellum or paper or painted were also made during this period. These are all within the neo-Classical genre, with the exception of the painted “house” or “cottage.” Masses of fakes have arisen again, the latest model in pink with crackled varnish!

Before abandoning this period, we must mention the turned fruit caddies, mostly in the shapes of apples, pears, and melons. These were made in great numbers throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Alas, they continue to be made and often sold as the earlier examples. Patina is most important when buying such an item; it makes the difference between a few hundred and a few thousand dollars.

Caddies which were made during the 18th and early part of the 19th centuries were finished in wax or varnish. Varnishes varied from maker to maker, mostly being mixtures of turpentine, wax, copal, or other resins. This explains the different way varnishes have crackled and aged.

Regency

The next great period is the Regency. Historically it lasted from 1810 to 1820. Stylistically it stretched from the time George (1762-1830) came of age as the Prince of Wales, until his death as George IV in 1830. The good news is that tea chests and caddies from this period are difficult (although not impossible) to fake. George was a great style guru, and he surrounded himself with people of taste, panache, and aesthetic boldness. Good taste in the sense of quiet, subdued proportion was challenged. The age of this George was quite different from the age of his “farmer George” father. Out went the straight lines and the flat decoration. In came forms that undulated and danced in curvaceous and structured forms.

In came decoration that stimulated the imagination and dazzled the eye. The Regency was the time of the second phase of neo-Classicism. Egypt was revealed to the world. Napoleon and his army were awed by the temples of the country they went to conquer. So was Nelson and the archaeologists and scholars who either accompanied them or followed in their footsteps. Structure, strength, and power became the buzzwords for the aesthetics of the time.

Caddies, especially tea chests, took to the new shapes, and they were made magnificently. Tapering, concave, bombe boxes with pediments and pedestals are a distillation of an ancient form through the informed mind of the cabinetmaker, who had attained a high level of expertise. The cabinetmaker was not a mere woodworker, but a professional who understood the orders of architecture and demonstrated a highly sophisticated grasp of his subject.

Decoration was inspired by antiquity, but it did not copy painting or inlay. It took ancient motifs such as palmettes and anthemions and rendered them into brass inlays that contrasted well with the newly fashionable dark timbers. Sometimes the decoration was arranged in columns, thus drawing the eye upwards, as if at the entrance of a temple. Richly figured rosewood with its dark striations became the wood of choice, although mahogany and fruitwoods were not entirely supplanted. French polish was now preferred to the earlier finishes, and this gave a glossy, smooth look to the surfaces. The boxes were mounted on turned wooden or gilded brass feet and often had side carrying handles. These, too, drew their inspiration from ancient forms. They were either clusters of fruit and flowers symmetrically arranged, or for the more austere pieces, lion or eagle handles and paw or talon feet were used.

Under the influence of George Bullock (d. 1818) the eminent royal cabinet maker, the brass decoration became less rigid and more in the nature of scrolling flora. It was still symmetrically arranged and very controlled, but the motifs were more in the nature of native leaves and flowers.

Tortoiseshell caddies were also made in the new shapes, sometimes at the expense of the figure of the shell. Caution, there are many fakes. Buyer beware.

William IV and Victorian

The next step was a slight softening of the look, heralding the prettier, more accessible taste of the Victorians. The feet and handles were made of turned wood and the inlay was in mother of pearl. The early examples dating from the 1830s feature stylized floral designs. As the century progressed, the inlay became more naturalistic. Sometimes a marquetry of two contrasting woods, such as bird’s eye maple and rosewood was preferred to mother of pearl.

Victorian caddies followed the Regency styles but they were on the whole simplified in shape and prettified in decoration. Shaped chests or caddies rarely had as many levels of construction as the Regency examples. The veneers were mostly machine-cut and except in exceptionally good quality pieces, they were much thinner than before. Walnut became the favorite timber. Some quality caddies and tea chests were made in coromandel wood and were decorated with inlays of engraved brass, brass thin lines, and shell. The designs were mostly floral.

Some late Regency and early Victorian tortoiseshell caddies were very successful combinations of shape and decoration, making good use of the malleability of the material. Heavy, undecorated shapes are less successful and widely faked. The new fad for the neo-Gothic translated well into embossed tortoiseshell.

By the end of the 19th century, caddies featuring bands of geometric inlay were made in great numbers, mostly in simple straight shapes or with domed tops. Pre-packed inexpensive tea spelled the end of the era of the caddy.

The caddies we have discussed so far are in the mainstream. There are, however, special groups which deserve their own consideration. Japanned, penwork, and painted caddies and chests are some of the best mirrors of the social and aesthetic mores of the period. They all have a charm all of their own, and they are often exquisitely eccentric. Sometimes boxes were supplied “in the white” and decorated at home. Instruction and design books circulated ideas and techniques.

Japanning was an attempt at imitating oriental lacquer and was practiced mostly during the 18th century. Surfaces were prepared with gesso and then the designs sculpted with raised gesso. They were then painted, gilded, and varnished. The scenes were mostly of chinoiserie, a hybrid style developed as a vision of Cathay – the wondrous Orient – which was beginning to take hold of the consciousness of the fashionable world. Penwork and painting was a natural development of Japanning and “engraved” 18th century inlay. The technique and decoration were probably influenced by Anglo-Indian work, which was introduced in the mid-18th century.

Boxes in the “Chinese gout” were mentioned by a socialite, Mrs Montagu, as early as 1749, as made in the spa town of Tunbridge Wells, in Kent. These were probably Japanned and painted. Tunbridge Wells, where the makers were on the ball as far as box-making was concerned, made all types of fashionable work, including penwork and painted boxes with identifiable surviving examples.

The Scots, too, perfected penwork. The creator of the Scottish box art industry was Lord Gardenstone. In 1788 he brought a Mr Brixhe, an excellent artist from the town of Spa in present day Belgium, to paint boxes made by Charles Stiven, who was already working in Laurencekirk, East Scotland. Brixhe was famous for his painting of flowers and also for fine ink drawing, which imitated lines within marble. Soon the penwork was developed to depict representational scenes.

In England, Chinoiserie was the most popular theme, followed by naturalistic and neo-Classical designs. The Prince of Wales feathers motif, popular from the Regency crisis of 1788 up to1810 was executed on caddies of 18th-century form. A very superior group of painted ware, which was obviously painted in the same studio, in our opinion hail from Cumnock in West Scotland.

Caddies from Tunbridge Wells became very distinctive after 1800, when the area developed its own style. The early 19th-century examples were made by juxtaposing carefully selected pieces of timber in geometric designs. The area was famous for the variety of trees and the makers for their skill in utilizing the natural peculiarities, colors, and figures of the wood. After 1830 the wood mosaic technique was developed and used to create complex designs, which reflected the mid-19th-century taste for native natural themes.

We will conclude with Chinese export caddies, because they are indisputably the soul of the whole tea trade. They were brought over to England by the merchants of the East India Company, the very people who introduced us to tea. Most date from the first half of the 19th century, with rare 18th-century examples. They were traded in Canton and carried in the same ships as the tea. They often depict scenes of oriental life as witnessed by the merchants. More rarely, they have representations of Chinese culture or history and even of tea trading. They encapsulate the very magic of Cathay and no collection can be considered complete without one.

The images and text of this specially commissioned article © Antigone Clarke & Joseph O’Kelly, www.hygra.com.

Antique Boxes, Tea Caddies, & Society 1760-1880

The box represents great temptation. Just think of Pandora. “Open me” it says. Irresistible, a beautiful box’s charm is overwhelming. So too, is the charm of this book, in which antique boxes and tea caddies are brought to life along with the people who inspired, made, and used them. The reader is guided through the aesthetic, cultural, and social influences of the years, accumulating a deep understanding of the form, decoration, and purpose of 18th- and 19th-century boxes. The extensive text covers wooden, tortoiseshell, ivory, papier mâché, and lacquer boxes. There are chapters on Anglo-Indian, Scottish, Irish, penwork, straw work, and Tunbridge ware boxes as well as on boxes made for special purposes. Captions include complete descriptions, values, and circa dates for all boxes shown. The 905 lush images include original drawings, magnificent photographs of complete pieces, and close-ups illustrating the structure and decoration of boxes. This is an indispensable companion for box collectors and a great read for those interested in the cultural forces that shaped the 18th and 19th centuries.

Related posts: