by Judy Gonyeau

“All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players” – William Shakespeare, As You Like It.

At no other time and place was this truer than in the early surgical theatres, where people would pay admission to attend a medical procedure. The drama would play out over many hours or days – sometimes with a small quartet or a flute to juxtapose the gruesome atmosphere of the event. The plot unfolded in the gripping trial of life and death: the doctor as the hero, the disease or condition as the antagonist, and the patient (often a corpse, but sometimes a live demonstration on a willing and typically poor person) as the victim. Things would unfold with pain, strife, gore, smell, and dialogue complete with screams and arguments on a set designed to allow its audience full view of the event. And then there is the artist as the “chorus,” recording and reflecting the event for posterity to be viewed by both the studious and the curious over time.

From the very beginning the body and its care and treatment has been a wonder to behold. It has it all: beauty, mystery, emotion, and infinite variety. Artists study shape and form throughout their lives, trying to capture every muscle, every hair, every nuance. But what happens when the body is injured, disease-ridden, disfigured or deformed? That is when artists step it up a notch to observe not only the body itself but how these factors affect its form, color, and response.

Even in the days when autopsies and dissections were against the law, physicians and artists would work with “body snatchers” to learn how everything under the skin worked. While the doctors were able to literally delve into the body, the artist could now accurately reflect what was beneath the skin and provide a visual representation to be used by students of medicine.

The artist’s strengths in observation were used to document mankind’s social and physical qualities, actions, reactions, and more over time, giving the viewer something to sense as they looked at a painting that reflects what their subject is feeling and thinking through all those details. In the world of medicine, art in its many forms is having a renaissance for practitioners and collectors.

First, a look at some of the classics.

The Master: Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicholas Tulip

This is a painting that appears to have it all. This 1632 oil on canvas is considered one of Rembrandt’s early great masterpieces showing Dr. Nicholas Tulip discussing the anatomy of the cadaver’s interior flexor tendons of the arm at a gathering of his peers—most of whom paid to have their portraits included in the painting—looking at the physician and the viewer as if they played a key role in this historic event. Rembrandt, just twenty-six at the time, was perhaps determined to show his strength of observation down to the finest of details while placing portraits of the “consulting physicians” in order by rank and amount of payment within the scene.

While the painting looks to be something that took place in a pristine environment, it is important to remember there was most likely a good amount of blood, and those white cuffs, as well as the body, were most likely not so pristine. Each piece of this painting was done in stages, from the intricacies of the arm interior to each individual portrait. This was how medicine among the learned was reflected at the time – exuding knowledge from every face to bring the viewer a sense of confidence in the work done by these men. This painting set the design elements for other paintings designed to serve the physicians well for quite some time. Note the 1730s painting Dr. William Cheselden giving an anatomical demonstration to six spectators of the Barber-Surgeons’ Company (attributed to Charles Phillips), white cuffs and all.

(Note: A wonderful work of historical fiction that is lauded by many medical websites on this painting is The Anatomy Lesson: A Novel by Nina Siegal that brings added dimension to this famous painting.)

In this oil-on-cardboard painting of Dr. Pavlov (of Pavlov’s Dogs fame), he is seen in action as he is about to deal a healing blow on a patient’s knee. The artist was a friend of the physician and his daughter had a surgical practice at his clinic. Known for his portraits and paintings of life in Russia, this image shows the force of some of the extremes surgeons used to produce results. It is unclear if the patient is under any type of anesthesia – only that his eyes are covered as the almost serene faces of the surgical staff are focused and ready for whatever may come next: severe pain, an outburst, and most certainly an explosive reaction.

Dr. Péan Teaching His Discovery of the Compression of Blood Vessels at St Louis Hospital, 1889, by Henri Gervex

In stark contrast to Repin’s painting is the gentlemanly approach as the scalpel is lifted by Dr. Jules-Emile Paen in the 1889 painting by Henri Gervex with the lengthy title Dr. Péan Teaching His Discovery of the Compression of Blood Vessels at St Louis Hospital. This snapshot of the modern medicine of the time includes images of state-of-the-art surgical instruments intended to “inspire awe” in the hearts of up-and-coming surgeons. The delicate state of the patient doesn’t hurt either. While not his first try at medical art, this stands in stark contrast to his much earlier Study for Autopsy at the Hotel-Dieu depicting the main Paris morgue of the day – an unusual venue to depict medical science at the time.

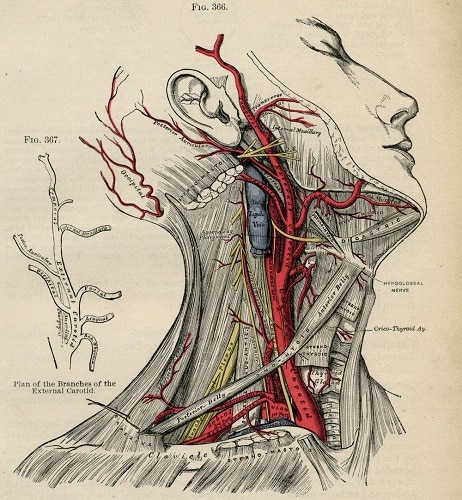

The Ultimate Resource: Gray’s Anatomy with illustrations

The 1858 Gray’s Anatomy reference tome on the human body continues to be updated and refined by experts in their field to this day. Henry Gray was an up-and-coming anatomist seeking not only fame but prestige. Broadly known to have absconded with the majority of the medical information from other already-existing resources, Gray’s ambitious nature led to his name often being attributed not only to the text but the illustrations of the book. Gray made note on the printer’s proof for the title page that the illustrator’s name should be much smaller and moved to the bottom of the page. But it was those simple illustrations, accurately and lovingly drawn, that continue to inspire the clean and clear drawings many turn to today to view our bodies from the inside out.

The illustrator was Henry Carter, a fellow physician and illustrator who worked tirelessly side-by-side with Gray as they conducted their research. In the article Gray’s Anatomy’s Forgotten Illustrator by Amanda Smith, fellow author and Gray’s expert said that “The title page of the first edition makes it clear that this anatomy book was created through dissections performed jointly by Gray and Carter. It reminds you that the drawings are of real people. … Carter, because of his religious background, sees the human body as the image of God. If you think the human body is the image of God, then you’re not going to treat it badly in illustrations; you’re going to treat it with dignity.”

Medical Technology As Art

In the world of medical art, the contraptions developed over the past century are now sought-after for their innovation and the design aesthetic involved in engineering their purpose into a useable tool. Mariano Chavez of Agent Gallery in Chicago (agentgallery.com) prides himself on gathering an eclectic mix of medical technology being offered for sale, which are photographed in a way that evokes the sculptural quality of these devices. Upon procuring a recent item—a rare Ophthalmophantome (eye surgical phantom) used by surgical students specializing in ophthalmology—he is thankful. “I am happy it survived this long.” Like a collector with a new toy, he even put together a video to demonstrate how it was used.

Clientele for Medical Technical Art are often physicians, museums, and others in the medical field, but crosses over to anyone interested in vintage tech, engineering, and design based upon use.

Today, fine art is also making its way into medical collections for its ability to enhance the observational skills of physicians in a world where technology has taken the doctor’s eyes off of the patient to rely on the image on the screen. Medical schools and teaching hospitals are now incorporating fine art to train the eye to see what was often unknown at the time.

For example, placing an image of Rembrandt’s Bathsheba at her Bath (1654) shows the model for the painting likely had breast cancer with axillary lymph noted involvement, among other observations able to be made about her overall health. In Caravaggio’s Young Sick Bacchus (1593) the ravages of Alcohol Use Disorder over time, something Caravaggio himself was quite familiar with, are evident thanks to the artist’s ability to show the jaundiced complexion. By using artwork to sharpen medical students’ powers of observation, it is hoped they will learn to see the diagnostic evidence before them before ordering expensive tests.

Collecting art within the theme of medicine and all things medical is stimulated by a discerning eye, a love of detective work, and a strong sense of curiosity. The revival of these classic works of art together with a new interest in vintage technology, are making the market stronger for the collector and the dealer.

“Last scene of all, that ends this strange eventful history, is second childishness and mere oblivion; sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.” – end of the speech given by Jaques in As You Like It.

Related posts: