The original props. The one-sheet posters. The lobby cards. The sculptures and statues and autographed photos of the stars of the cinema. All of these are hugely fun categories for collectors – categories that tend to be the most visible and the most popular when it comes to vintage Hollywood.

But there’s a vintage movie collecting category that’s a little off the beaten track. It’s made up of the “tools of the trade” that brought these cinematic treasures to us through the years. These are the projectors that showed these films, and the films themselves – artifacts that tended to end up in closets and attics in greater numbers than posters and photos. Generally speaking, projectors do just fine in closets and attics, but films are another story.

Pro Versus Amateur

Movie projectors can generally be divided into two main types. The first type is the unit used by the professionals down at the Orpheum or the Rialto or the Bijou; these were large, complex machines that showed either 16mm or 35mm films, the millimeter number referring to the width of the film. Films shot and projected in the 35mm format were highly flammable as they contained nitrate – an ingredient that often was referred to as “flash paper” due to its unstable nature, which often made its presence felt as a film passed through a projector just in front of a blazing hot lamp. As old nitrate films get older, they turn to powder, which is even more flammable.

In 1923, Kodak introduced 16mm film, which was made from cellulose acetate. Although acetate film will melt and burn, it won’t spontaneously combust the way 35mm film can. The 16mm format, therefore, is often referred to as safety film. As it ages, the images on an acetate film will fade and the film will start to smell like vinegar as it decomposes.

The vast majority of the large theater projectors that showed these films from the 1920s through the 1970s wound up on the scrap heap, although examples still can be seen in museums and private collections.

It’s much more common these days to run across the second type of movie projector, which is the kind that was manufactured by companies such as Keystone, Argus, Revere, and Bell & Howell. These were the units aimed at the consumer, for showing movies at home. The earliest home projectors showed 16mm film; in 1932, Kodak introduced 8mm film, which was less expensive than the 16mm product. The standard 8mm format also is called regular 8, to differentiate it from Super 8 – a format introduced by (you guessed it) Kodak in 1965. Despite being the same size film, regular 8 and Super 8 are not inter-changeable: although some projectors are “dual 8,” meaning they’re equipped to run both, the sprocket holes are smaller on a Super 8 film than on regular 8. It is pretty easy to ruin a Super 8 film by trying to run it through a regular 8 projector, and visa versa.

The Passage of Time

All of this, of course, assumes that it’s fine to put vintage films into vintage projectors, fire them up, and enjoy movies the way they did in 1948 or 1973. Except sometimes it isn’t. We’re talking here about films that have had 50 or 60 or 80 years to lay around and become brittle, along with projectors that often haven’t been run since Lyndon Johnson was president. “As a serious preservationist I get asked about projectors all the time,” says Nick Spark, owner of Los Angeles-based Periscope Film, a film preservation service. “If you actually have truly rare or unique films, like home movies, the last thing on earth I would recommend is to buy a projector and project them. That is a recipe to destroy films. People don’t realize that all projectors are antiques at this point—even ones from the 1970s are 50 years old—and unless serviced, they will scratch and break films. It is best to simply pay a knowledgeable company or individual to make scans to digital.” It’s one thing to damage your Marx Brothers or Charlton Heston film, but irreplaceable images of loved ones or historic events should be digitized; you then can have your original films and canisters returned, and they can make great display items.

The same is true of vintage projectors, which, in terms of design, often hold a mirror up to the era in which they were made. Many 1920s and 1930s projectors are wonderful examples of art deco-inspired design, with lamp housings sporting parallel heat-sink lines and pebbled paint finishes. These things just scream “pre-war America,” and, when displayed with their film reels in place, can give you a glimpse of what it was like when your friends up the street invited you over to watch the latest Claudette Colbert flick.

Following World War II, some projector manufacturers followed the lead of the makers of other household products such as refrigerators and record players, giving their projectors a similar mid-century look that emphasized rounded edges and, in some cases, a somewhat “space age” look. This was especially true of many of the more portable projectors manufactured during the 1950s.

Some projectors (including many toy and “junior” models) actually were hand-crank powered, which may have saved on cost but likely got old fast for the operator. In the 1920s-1930s, Bridgeport, Connecticut-based Lindstrom Tool & Toy Company offered a 16mm model that stated on its label, “For use with slow burning film only.” This was an acknowledgment that hand cranking was more likely to lead to film catching fire than with a standard motor-driven model due to the operator slowing/stopping the film directly in front of the hot lamp, resulting in the film heating up to the point of combustion.

Many other projectors were marketed as toys over the years, including one that tied in very well with the movies themselves: Keystone’s Mickey Mouse projector was a 16mm unit made during the 1930s and sold with films of Mickey Mouse cartoons.

Those interested in this projector will have to compete with collectors of Mickey Mouse/Disney memorabilia, which tends to drive the price up. Other toy projectors included the Eastman Kodak Kodatoy, the Excel “Jolly Theatre” projector, and a plastic crank-powered model made during the 1950s and 1960s by Brumberger of New York.

As with most antiques and collectibles categories, selling prices of vintage projectors vary widely depending on condition and model. The good news is that many projectors survived the 20th century and they turn up often at flea markets, at antique shows, and on online auction sites. Because it’s such a “niche” category, you often can find even 1930s and 1940s projectors in serviceable shape for $50 to $100.

Of course, if it’s complete with the original case and/or box and instructions, and in top condition, the price will head North from there.

Boxes and Canisters in Film Memorabilia

Films in their original boxes, or canisters, turn up surprisingly often. Collectors of films actually shown in movie theaters are an endangered species; before the advent of videotape (and then of course digital media), collectors battled one another for the choice examples in this category, to own and show to friends and other enthusiasts. But the number of these collectors has been dwindling for decades as technology continues to advance. “I would say it’s a literally dying hobby,” says Ken Segal, a New Mexico collector who was given his recently deceased grandfather’s 8mm Bell & Howell standard 8mm silent projector when he was ten years old. “So much film degrading or being trashed after digitizing. Also, who can compete with the quality of relatively inexpensive DVDs and Blu-rays?”

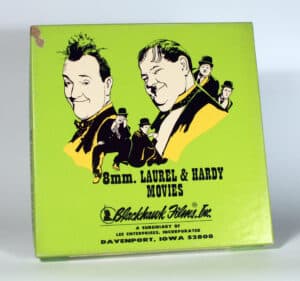

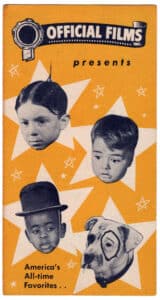

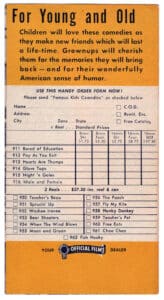

Commercially produced films made for home movie projectors are another story. These can be found both in 8mm and 16mm, as short as 50 feet in length up to 800 feet. Over the years, the subjects and titles of these films covered everything under the sun, from comedy to horror and science fiction, from sports to history and travel, and on and on. These films often were condensed versions of longer movies, but for most people, that didn’t matter. Just being able to show a Laurel and Hardy or a Gary Cooper movie in your home was a powerful draw with these films.

Two of the largest sellers of these “home Hollywood” movies were Blackhawk Films, in Davenport, Iowa, and New York-based Castle Films. For movie buffs in the 1960s and 1970s, getting the latest Blackhawk catalog in the mail was a little like Christmas morning: new titles, sale and promotional items, and descriptions of the movies being offered made for an effective sales tool.

While there undoubtedly are collectors of most categories of films, it’s the 1930s through 1960s horror and science fiction films that are most in demand with collectors. Rather than acquiring them to show with a projector, most buyers part with their money because they love the artwork on the film’s box. Classic comedies by legends like Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin, among others, also have a strong following.

Despite the box art being a key reason these films are in demand, you don’t want to buy one that’s in a state of decay. “If a film is stiff, warped, has a vinegar smell, and/or is brittle, it’s a big red flag, especially if it’s a commercial release,” says Ken Segal. “But with modern chemical treatments and patience, it’s no longer an automatic death sentence. [Products such as] Filmrenew and FilmGuard can do wonders. The success stories I’ve read are impressive. We’re talking months of soaking in Filmrenew to get it pliable enough to scan [for digital conversion].”

“Go-With” Items

There are other film-related items that are collectible and that make for interesting displays. Small bottles of oil, offered by some manufacturers so that owners could keep their projectors in good working order, look great when they’re parked next to a vintage Filmo or Apollo. So can replacement lamp bulbs, which often came packaged in boxes with artwork that was very evocative of its era. Of course, like any light bulb, these tend to be fragile, so finding one unbroken in a sharp original box is a find.

Metal film canisters and reels have a wonderful vintage look and vibe, even if there’s no film with them. And if you have the space and the interest, film editing machines and splicers can make for an interesting collection and display. These don’t turn up very often at in-person shows, but eBay usually has a number of them up for sale.

For that matter, finding original film catalogs and flyers, whether from Blackhawk or any other seller, can be a challenging undertaking. Catalogs and flyers tend to be thrown out once they’ve been thumbed through, and perhaps the fact that film was being replaced by videotape and then digital media helped hasten the demise of most of these documents.

For those interested in learning more about vintage films and projectors, Facebook has an informative and helpful group called “8mm, 16mm, and 35mm Film and Projector Collectors.” Once you join, you can see and learn about a variety of films and projectors, but be warned: it’s highly addictive stuff.

Douglas R. Kelly is the editor of Marine Technology magazine. His byline has appeared in Antiques Roadshow Insider, Back Issue, RetroFan, Diecast Collector, and Buildings magazines.

Related posts: