By William A. Turnbaugh, Ph.D.

Native American traditions and mythology highlight the regard that the New World’s people have long held for their smoking pipes. Links between the tobacco pipe, the gods and the tribe stand forth in the belief systems of many American Indian societies. For most, their pipes symbolized group identification and cosmic affiliation. Origin myths of the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and others credit the tobacco pipe with a role in the genesis of the tribe, having been bestowed by a culture hero at the very beginning of the world.

Archaeological research substantiates the hoary antiquity which such legends ascribe to native smoking pipes. Even allowing for the likelihood that earlier forms go unrecognized if they were made of unfired clay or perhaps organic materials such as bone, wood or bark, we do know that Indians have smoked pipes for thousands of years.

A period of more general pipe usage seems to coincide with the northward spread of maize agriculture in the early centuries of the modern era. Pipe forms reached an apex of artistic achievement and variety around this time. Midwestern moundbuilder sites yield elegant carved stone effigy pipes. The faithfully sculpted birds and animals on these little works of art must have held special significance for smokers.

Most Native American groups employed their smoking pipes to send smoke heavenward as an offering or message for the Great Spirit. Naturally, the combustible materials that filled the pipe bowls were carefully selected to please the gods. Tobacco was the standard choice, although other botanicals with special properties were sometimes chosen. As the most favored “supernatural” plant among the New World’s original inhabitants, tobacco might also be chewed, drunk as an infusion, smoked as a cigar or cigarette, or offered directly to wind, water or flame. For native peoples the “spirit power” of these plants dictated their use in a prescribed manner that went beyond simple pleasure or indulgence.

The popularity and endurance of smoking pipes as an element of Native American culture lies in their deep symbolism and their perceived mystical associations. Even when considered apart from tobacco’s important role in the smoking process, the pipes themselves were linked with life forces and other elemental concepts in the belief systems of many societies. Thus, the raw materials for the pipes, their shapes and ornamentation, the rules pertaining to their use, as well as the various combustibles tamped into their bowls were all meaningful and significant.

Mid-continent tribes favored pipes skillfully carved from an especially attractive red stone sometimes spotted with salmon-colored flecks. The 19th century artist of aboriginal America, George Catlin (1796-1872) first recorded a Sioux legend about the famous Minnesota quarry that was the key source of this pipestone. Having summoned the nations together at that place very long ago, the Great Spirit broke a chunk from the ledge of red rock and shaped it by a turn of his hands into a large pipe, which he filled and smoked to the cardinal directions. As he did so, the manitou admonished those gathered there to work in harmony on that hallowed ground and to fashion only pipes of peace from the sacred stone. Longfellow later worked this legend into his epic poem “Hiawatha.”

Thus, the importance of catlinite, named for the artist and the most valued of all pipestones, can be attributed to more than just its rich hue and its workability. Some held that the stone’s red color derived from the congealed blood of bison anciently consumed by the Great Spirit. An even more prevalent tradition among the Plains tribes who quarried the stone was that it symbolized the flesh of their own ancestors. So holy was this substance and so strictly did they interpret the Great Spirit’s injunction to use it only for pipes, that the local Sioux had tried to prevent Catlin from reaching the quarry, lest he remove some stone and thereby make a hole in the red man’s flesh from which the blood would spill forever.

Plains Indians exploited several different local sources of red stone resembling catlinite for pipemaking, but the extensive quarries near the present-day town of Pipestone, in southwestern Minnesota, were by far the most important. For centuries before Catlin’s uninvited visit and description in 1836, natives had wielded heavy stone mauls to access the seam of metamorphosed red claystone embedded in a tough quartzite matrix. On the authority of William Clark, explorer, territorial governor, and long-time student of Indian lifeways, Catlin asserted that every tribe in the Missouri River region had obtained pipestone there despite the exclusive presence of the Sioux in the vicinity at the time of his visit.

Many tribes sought to resist the unwelcome changes associated with advancing European culture by adopting formalized rituals, including elaborate pipe protocols. Special smoking pipes were devised for important gatherings. Some of these ceremonial practices had originated in the northern prairies. It was perhaps because of its primary association with these regions and activities that the handsome inverted-T-shaped catlinite pipe bowl became the most widely accepted style. Less common was the protohistoric disc pipe. Later idiosyncratic varieties are sometimes encountered. Pipes intended for personal use usually took a different form and were much smaller.

The meshing of symbolic meanings that resulted in the calumet concept seems to have occurred at a relatively late period. The calumet’s popularity then expanded throughout native America. References to its use became more frequent by the mid-17th century. Historical documentation thereafter records the rapid diffusion of the instrument and its accompanying rituals along major waterways and communication routes.

The use of a ceremonial tobacco pipe in sealing pacts and in arbitrating internal and external disputes became a widespread practice. Typically, Plains tribes such as the Kiowa used the pipe calumet as a diplomatic instrument having the power to bind participants to their word. These behaviors were recognized by non-Indians as well. Because whites noticed that solemn agreements made in this manner were seldom broken, they coined the term “peace pipe” to describe the device.

By the mid-19th century, when the Sioux were forced to relinquish the Minnesota quarry temporarily, catlinite fell under white control. Fur traders distributed raw pipestone among the growing number of tribes who desired pipes made of it. Even after rights to the source were restored by treaty in 1859, the Sioux consented to quarry and sell the stone to the whites, who then employed lathes and other equipment to turn out quantities of catlinite pipes and other trinkets for the Indian trade. Between 1864 and 1866, the Northwest Fur Company alone had manufactured and sold nearly 2,000 pipes, and by 1892 hardly any catlinite items were native made.

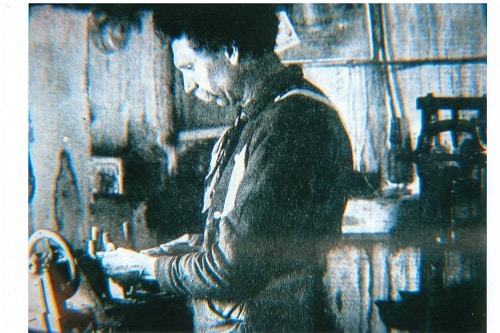

Today a scant handful of carvers continue to turn out pipes for Native American ceremonial use. Cultural demonstrators associated with the Upper Midwest Indian Cultural Center exercise their legal privilege to exploit catlinite resources within Pipestone National Monument. Employing basic carpentry tools, they turn out pipe bowls and small carvings for sale mainly to tourists and collectors. Their commercial work maintains a venerable craft activity and provides a tangible link to the past.

- Catlinite is hardened claystone with oxides giving it red color, metamorphosed to hardness 2.5.

- While the psychotropic effects of certain varieties of native tobacco, etc., then in use have not been fully studied, there is no debate that Indians accorded them an esteemed role in New World ritual and mythology long before Europeans arrived.

- The important pipe stones in specific areas varied with the underlying geology, from steatite or soapstone to fine sandstone, indurated clay, or even pumice and tuff. Many favored materials, and frequently the finished pipes themselves, were transported through intertribal trade networks or obtained by direct procurement over long distances.

- In some regions, both clay and stone pipes were employed, especially after white contact when steel tools made stone carving easier.

Related posts: