Now, while Rea may have been curious about the writings, his successor, Laura Bragg, was fascinated by them. Becoming The Charleston Museum’s director in 1920, Bragg had developed a vital interest in “Carolina clay” and, especially, the enslaved potters who worked it. Eventually, Bragg’s research, which included first-person interviews and repeated visits to long-abandoned pottery sites, would yield data quintessential to understanding the whole story of what was a once considerable enterprise, “Edgefield Pottery.”

The Beginning of a Local Industry

By 1860, The Edgefield district was about 950,000 square acres positioned midway between the Blue Ridge Mountains and the Atlantic Ocean on the western edge of South Carolina at the Savanna River –– what is today Edgefield, Aiken, McCormick, and Saluda counties. For most of the nineteenth century, it held dozens of family-connected potteries, each producing massive amounts of wares for use throughout the south.

The genesis for the eventual establishment, production, and commerce of South Carolina pottery is perhaps best attributed to the lackluster desirability for European-made porcelain, considered in the mid-1700s “an expression of the needs and taste of the peasantry” compared to the ultra-refined wares exported from the Orient. However, the discovery of kaolin-essential for making both hard and soft-paste porcelain-in the Carolina interior gave western ceramicists, they hoped, a way to produce wares comparable to those of their Asian counterparts. Getting their hands on it, though, would not be easy. Several expeditionary groups had already ventured inland to gather the so-called “Cherokee Clay.” Even Josiah Wedgewood sent agents to procure “an earth, the product of the Cherokee Nation in America,” but found the exploit too dangerous and expensive to continue.

The Story of Dave

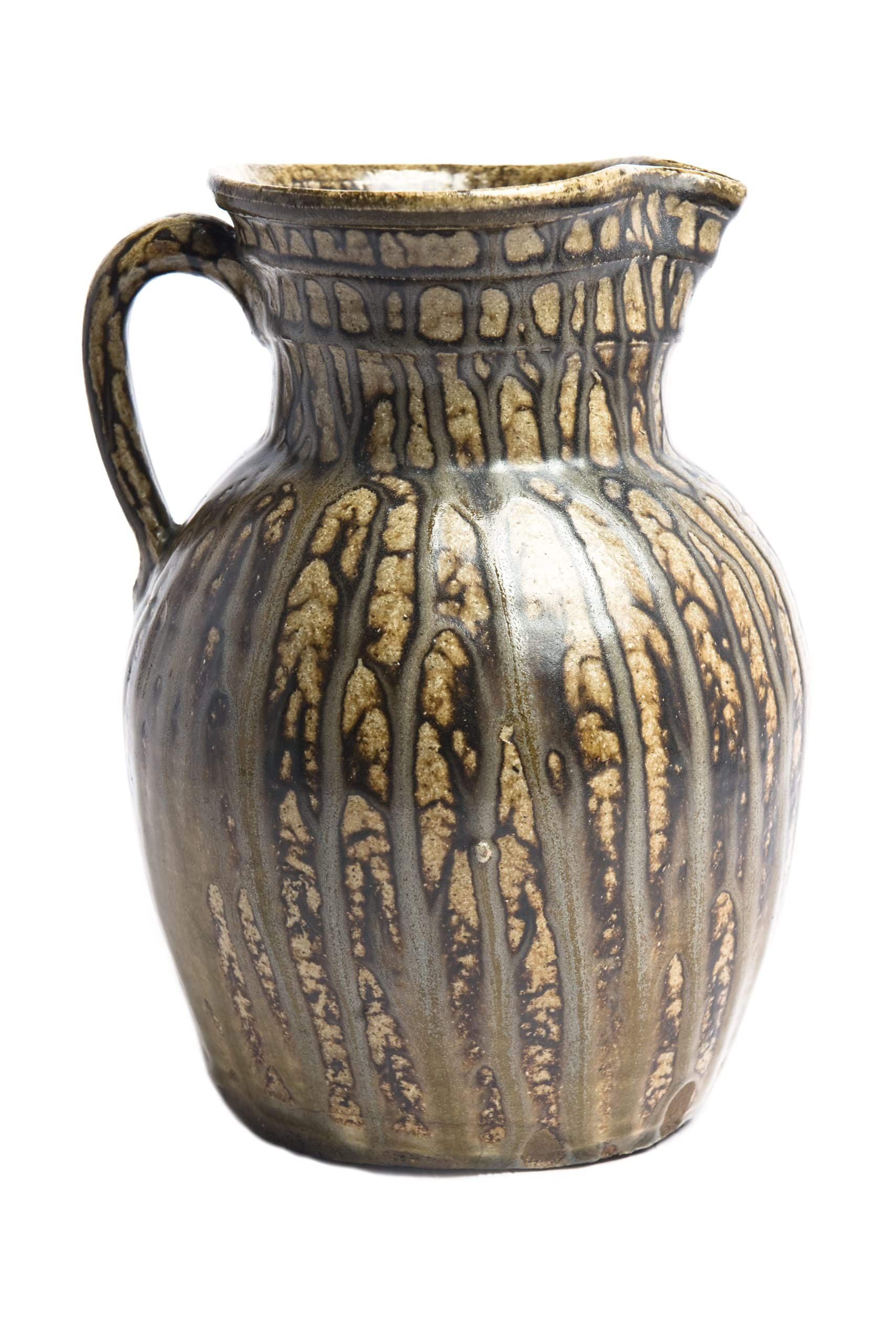

Pleased with Pottersville’s success, Abner Landrum eventually sold most of his stoneware interests to nephew, Harvey Drake who brought to the business an additional number of enslaved Africans. Of these, it was the “turners,” who were of particular value. Turners were the backbone of any pottery; each having a specific skill set to form clay into myriad vessels, and a potter called Dave was one of them.

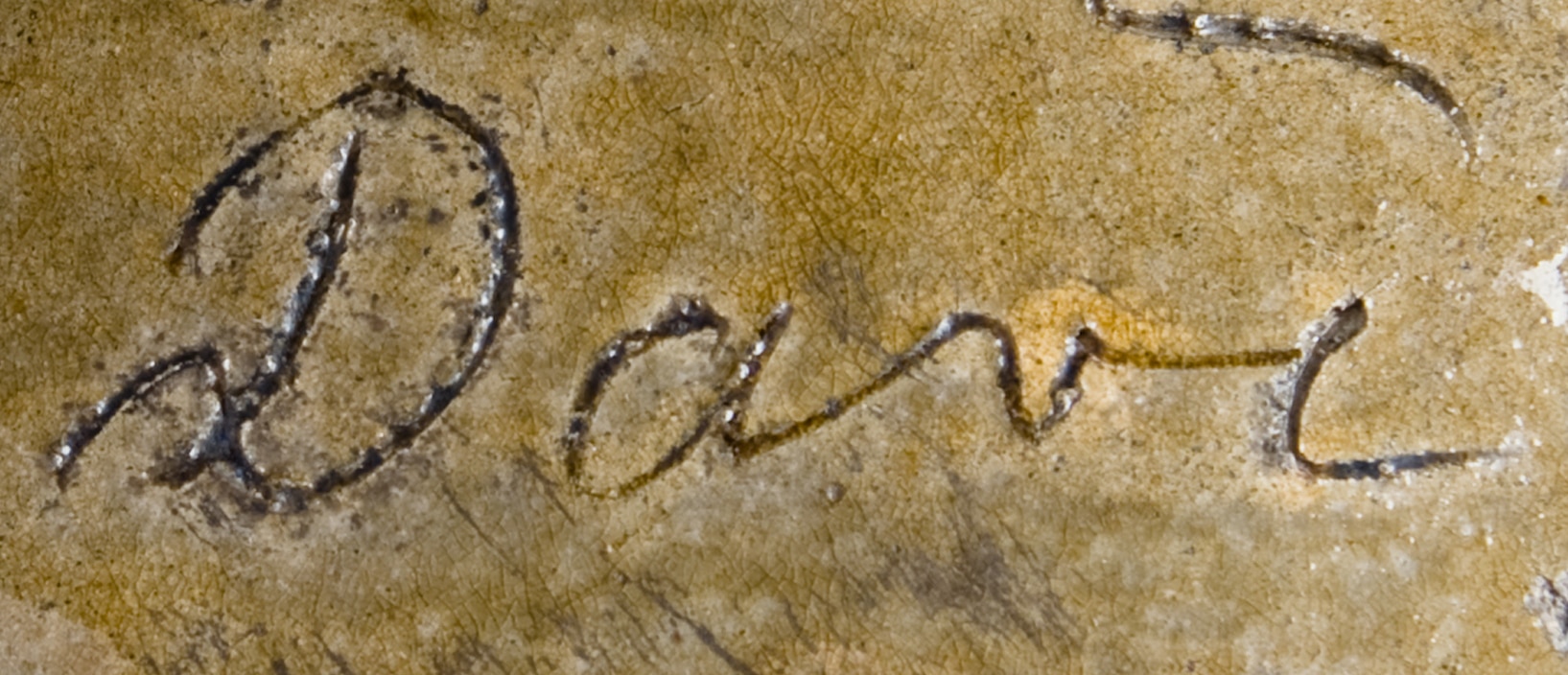

Born circa 1800, Dave first appeared in Harvey Drake’s 1818 mortgage as a “boy about 17 years old.” Though he had possibly learned stoneware by this age, he was certainly a skilled individual by the time Drake died in 1832, being valued at a relatively high price of $400 in the estate. Dave’s workmanship notwithstanding, perhaps most noteworthy for his time and place was his proclivity for signing, dating and, on at least thirty known occasions, inscribing poetic verse on his finished wares. Verse that, as far as the law was concerned, never should have been put there in the first place.

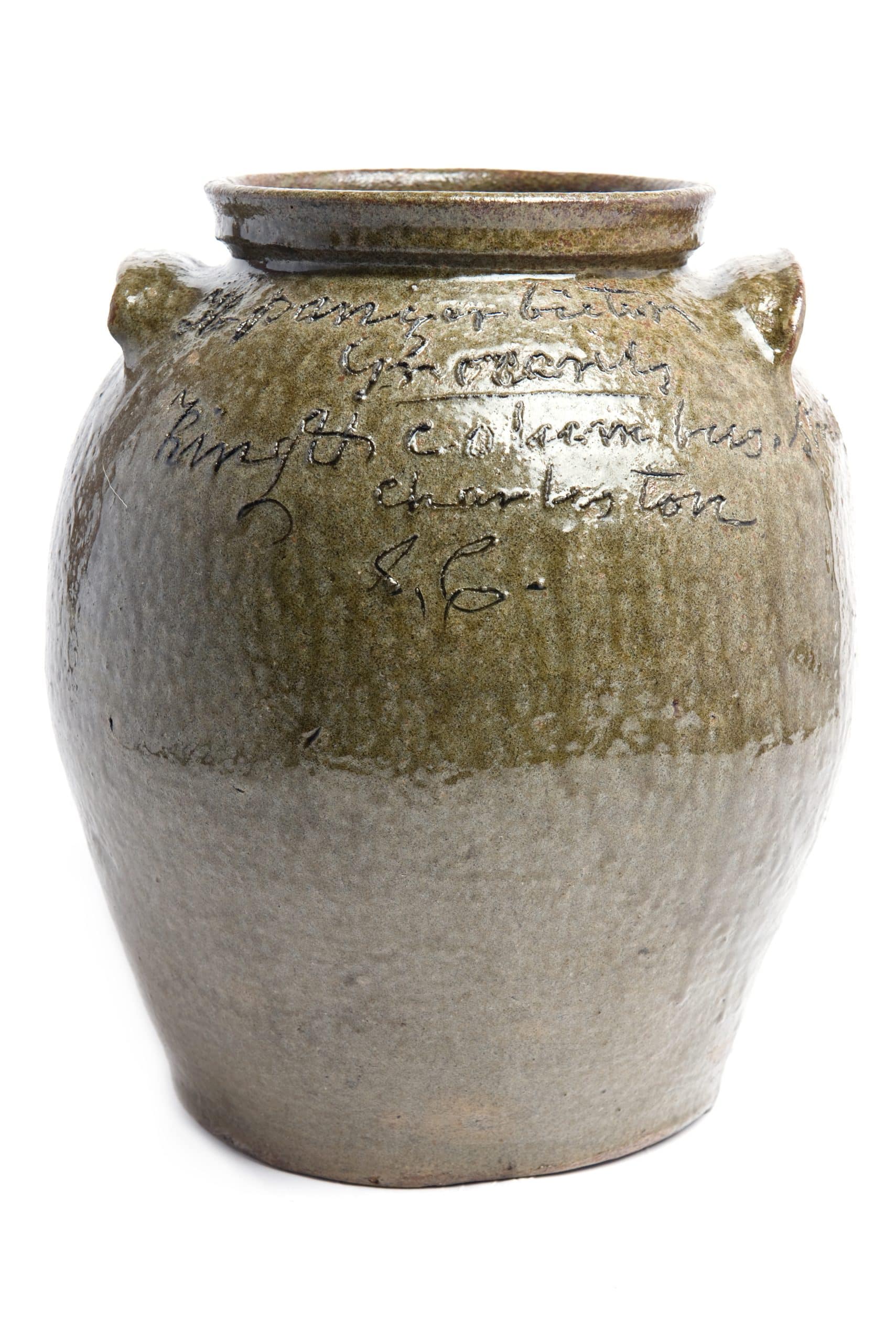

It is difficult to positively identify how, when, or exactly where Dave learned to read or write. Moreover, since he marked his works again and again in the face of oppressive laws against such a thing, how did he get away with it? Theories abound on both. In becoming literate, one hypothesis suggests that Harvey Drake taught him. A”profoundly religious man,” Drake could have felt the need to give Dave access to the bible, something a few denominations had advocated in spite of the law. Another theory is that he was put to work as a typesetter for the local newspaper, the Edgefield Hive, owned by Abner Landrum. It’s also possible that Lewis Miles, one of his subsequent owners, permitted Dave’s writings so that he could better personalize products for commercial buyers. One surviving example of this customization is a storage jar unsigned by Dave but inscribed by him for Charleston’s Panzerbieter Grocery Store.

Whatever his reasons and allowances, Dave’s poignant, whimsical, even romantic inscriptions create an almost personal connection to him. “His works … touch that part acutely attuned to the daily life of the rural community and the rhythm of routines, which require an innate sense of timing,” wrote Charleston artist Jonathan Green in 1998. ‘His hands on the clay and his foot on the treadle using his unique creative energy and personality to breathe life and history into what would otherwise be simply utilitarian objects.”

Gathering Elusive Information

Laura Bragg was likely feeling much the same way in the 1930s whilst gathering whatever data she could in pursuit of Dave’s elusive story and those of other Edgefield potters. Indeed, his remarkable messages present him as a creative and thoughtful man.

He makes known his wit in 1836: Horses, mules and hogs / all our cows is in the bogs / there they shall ever stay / till the buzzards take them away

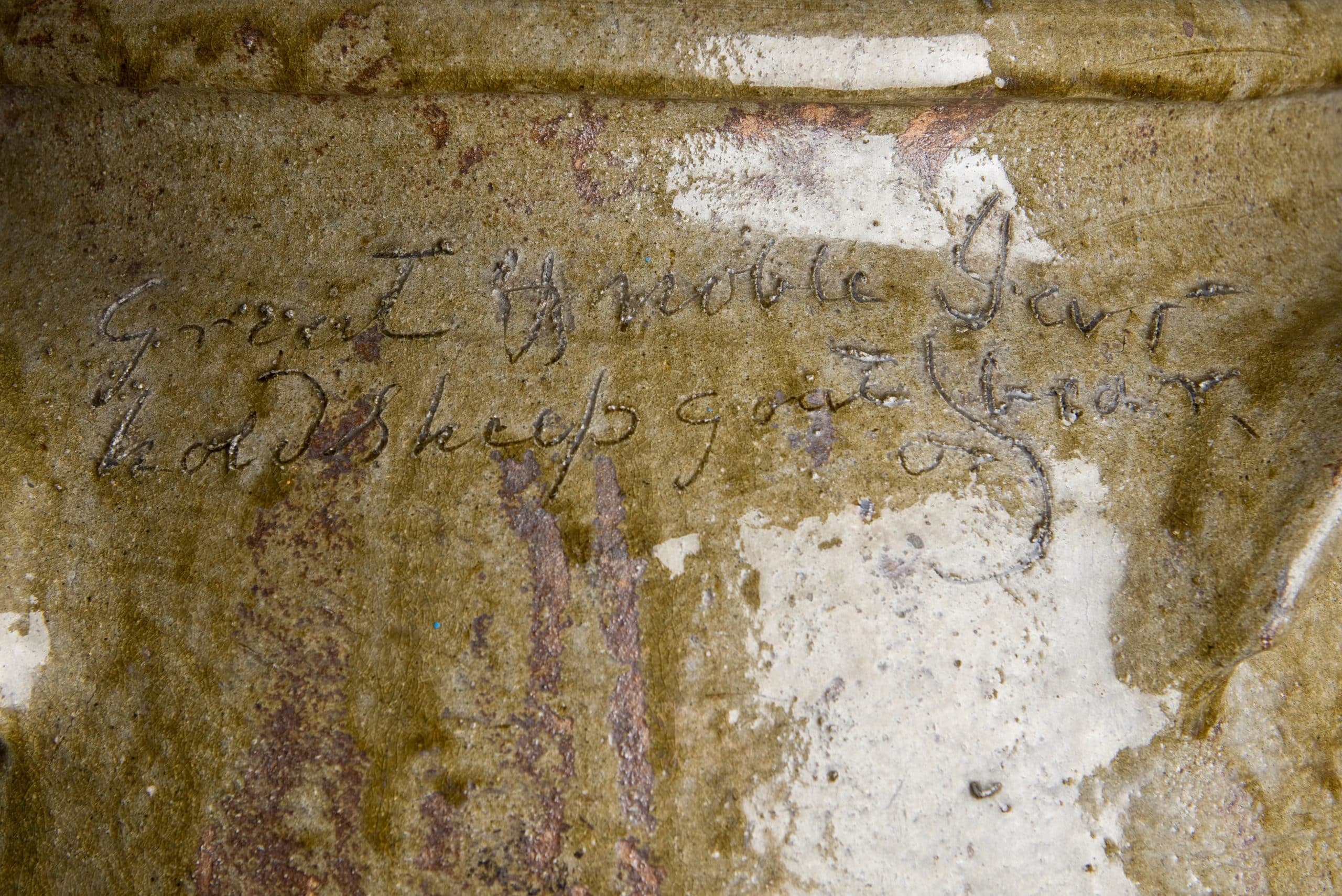

His business sense in 1858: This noble jar will hold 20 / fill it with silver then you’ll have plenty

And, regrettably, his lot in life in 1840: Dave belongs to Mr. Miles, wher the oven bakes & the pot biles

As Bragg continued her research into the 1930s, it was through a pair of interviews that uncovered an interesting, if not dramatic, detail of Dave’s life. On both occasions, she was told of a rather unfortunate accident that Dave endured during the course of his career. “Sure I knew Dave,” was how Mrs. Carey Dickson described him to Bragg. “It was at that time he belonged to old man Drake, and it was at that time he got his leg cut off. They say he got drunk and laid on the railroad track.” The other source, Mrs. Fletcher, who at the time was living in Lesslie, S.C., further noted to Bragg that she remembered Dave as being “mighty good” at turning pots, despite his having but one leg.

Now, it’s questionable at best as to when exactly Dave lost his leg. Dickson’s quote puts it somewhere before 1832, yet other notations in Bragg’s papers suggest the troubling event might have occurred much later. Whatever the case, the fact that Dave was able to continue making pottery with only one leg to drive his treadle is, in a word, remarkable. There were, however, some occasions where Dave had help. When Dave fell under the ownership of Abner Landrum’s brother, John, for example, he was paired with a fellow enslaved worker named Henry, who had lost the use of at least one arm. Henry, of course, still had two good legs to treadle the wheel while Dave put his hands to the clay. Later, while enslaved at Stoney Bluff in the 1850s, Dave, working together with another potter, Baddler, was put to work making large meat storage jars including the aforementioned 40-gallon piece, which Dave signed for both Baddler and himself.

Clearly, Baddler was a good match for Dave. After all, his name appears alongside Dave’s on more than this one pot. In fact, another mammoth 40-gallon storage jar arrived at The Charleston Museum in 1920, not quite a year after the first one. Just like the other, it was signed “Dave and Baddler” and, in Dave’s unmistakable penmanship, included the verse, “Great and Noble jar hold sheep goat or bear.” Amazingly, a quick comparison of the two pieces together reveals that both vessels are dated the same, May 13, 1859. Thus, if Dave is to be believed (and there is no reason not to), he and Baddler created these two massive works on the same day. To date, they are the largest Dave pieces known.

Post-Civil War Pottery

Like many enterprises in the American South, the Civil War greatly disrupted Edgefield’s pottery industry. Of the numerous potteries scattered about the Edgefield district in 1860, only two were operational in 1870. The wider availability of glass and metal containers didn’t help things either. By the mid-1880s, however, new generations of old potters were reviving Edgefield’s antebellum success, exhibiting the same durability and resolve of the stone-ware they produced. Landrum descendent Benjamin Franklin Landrum, for instance, by 1880 was producing upwards of $5,000 worth of stoneware goods.

An 1870 federal census listed David Drake, age 70, as a turner still making pottery near Edgefield. Alas, it was the last time he was ever recorded. Cohabitating with one Mark Jones, also listed as a “turner, age 35,” it’s possible that Dave spent the last few years of his life teaching a fellow potter to carry on his legacy.

All images courtesy of The Charleston Museum

Related posts: