America’s Catalog (1888-2010)

By Ian Moody

The Sears catalog – once a four-pound, 1,400 page colossus featuring a staggering 100,000 items – has been tossed into the dustbin of history, but is still appreciated today by collectors.

More than a century before Amazon’s grinning boxes would adorn the fronts of homes everywhere, there was a delivery behemoth that at one time accounted for one percent of the nation’s GDP. Everything from underwear and socks to washing machines and live chicks could be found in the pages of their catalog and delivered to your home. And if you were in the market for a place to store all of these purchases, you were in luck. You could even have shipped your very own, brand new home. All of this and so much more could be purchased through the Sears, Roebuck and Co. catalog that, at its largest, was a healthy four pounds, featuring a staggering 100,000 items across 1,400 pages.

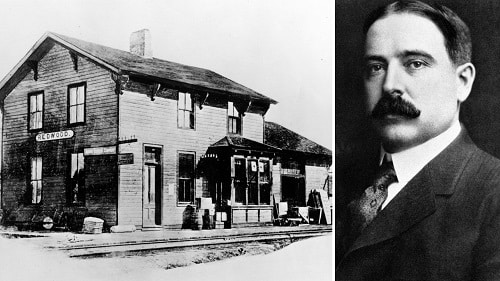

In 1886, Richard Sears, then aged 22, was working for the railroad as a station agent in Minnesota. He bought an order of gold watches from a wholesaler who had received the order in error and was disgruntled with the shipment. Sears bought the watches for $12 apiece and sold them at $14, despite the watches selling for $25 retail elsewhere. Already, the budding salesman began to show signs that he would one day run the self-advertised “Book of Bargains” and the “Cheapest Supply House on Earth.”

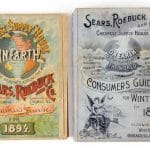

The next year, Sears joined watchmaker Alvah Roebuck in a store on Dearborn and Randolph Streets in Chicago. In 1888, Sears took a step towards creating the “Book of Bargains” when he began advertising watches and jewelry through the printed mailer, “The R. W. Sears Watch Co.” By 1894, the watch and jewelry catalog exploded in content to include bicycles, sporting goods and firearms, all packed within 322 pages. In 1895, eyewear was added to the catalog. Not only could customers order their desired frames, but would also be informed of their necessary prescription with the included eye-test. The next year, the catalog swelled from 6 inches by 9 inches to 8 inches by 11 inches, as groceries and washing machines were added. By 1899 catalog customers could even open their own movie theater thanks to Sears’ “Special Lecture Outfits,” which offered projection equipment, a screen, posters and admission tickets.

Sears, ever mindful that his company couldn’t afford to lose a customer, offered discounts beyond the company’s already low prices. A “club order program” was launched in 1897, allowing friends and neighbors to combine orders and receive discounts. Later, in 1904, the catalog instituted a “customer profit sharing” program in which a certificate was awarded for each dollar spent and could then be used towards specific items in the catalog.

As well as offering discounts to retain customers, Sears provided incentives to draw in new ones. To eliminate language barriers to ordering from their catalog, they hired translators. In 1904, wigs were added for African American men and women. Louis Hyman, a professor of history at Cornell University, even suggests that, in practice, Sears and its catalog competitors were champions for social change in African American communities throughout the South. At general stores in the Jim Crow era, store clerks would not serve black shoppers until white shoppers were finished with their purchases, and when given the chance to purchase their goods, Hyman argues they may have received an additional mark-up on the price of their purchases. These constraints were not present when shopping by catalog. African Americans received the same convenient and affordable services as everyone else in the country.

In most of their practices, Sears did not have good stewardship in mind, but simply good business. In 1905, Sears invited customers to experience their products through touch and sight, when they offered textured wallpaper and men’s suit samples. The next year, Sears showcased paint samples. Whether decorating the home or choosing the right ensemble, Sears strove to cater to every possible need.

Your Home, Delivered

In 1908, the same year the company’s namesake retired, the Sears, Roebuck and Co. catalog undertook its most ambitious offering: the mail-order “kit home.” Sears wasn’t the first to offer mailed homes, but the scope of their operation was massive. From 1908 until 1940, the year they ceased the product, more than 70,000 homes were sold to the American public. Throughout these years, customers could view 447 home designs. In the early years, most designs had such illustrious names as “Modern Home No. 52,” sold between 1908 (for $782) and 1913 (for $1,995). Apparently, the creative brass at Sears thought homes would sell better if they were given less chemical sounding names because by 1919, Sears homes had noble and classic names like “The Somerset” (1917-1925, $732-$1,576); “The Arcadia” (1917-1921, $267-$946); and “The Yates” (1939, $1,812-$2,058).

For an additional cost, customers could have features such as plumbing and central heating installed in their homes. For some customers, their Sears homes were the first to include such luxuries.

The process to own a Sears home was simple. Prospective home owners would only need to choose the desired design, mail in a check, and in a few weeks the necessary materials would arrive by train. The customer supplied the land and the manpower to put it all together. Sears assured its customers that even without highly qualified labor, their homes could be constructed in less than 90 days.

In 1911, Sears made it even easier to own one of their homes by providing customers with mortgage loans which were typically set at 6 percent over 5-15 years. To sweeten the deal, they offered no-money-down financing between 1917 and 1921. Sears may have been too eager to get customers into homes, for almost half of their $12 million sales were in mortgage loans in 1929, the same year the American economy tumbled into the Great Depression. The financial crash brought an end to Sears’ housing financing options. Mortgage loans were terminated in 1933, and in 1934 all mortgage accounts were liquidated to a sum of $11 million. The last “Book of Modern Homes” catalog was issued in 1940.

And That was Just the Beginning

It is astonishing to consider that this massive home enterprise was still only a fraction of Sears’ offerings. In 1910 Sears, for the first time, offered their customers an electric washing machine. Eight years prior to that, in 1902, customers could purchase an Acme Royal Range coal oven for between $17.25 and $22.14. In 1913, Sears introduced a specialty catalog for automobiles. In 1914, customers could build, furnish and even power their homes with Sears, thanks to their “Private Electric Lighting Plants.”

Just as impressive as the breadth of items Sears offered, was their ability to create exceptional brands. Almost a century ago, they introduced product names that we still recognize today: Craftsman (1928), Kenmore (1929), and Allstate Insurance (1931) were all children of the Sears Company.

As well as offering recognizable product lines, Sears also employed figures who today are still large in the American consciousness. Edgar Rice Burroughs, the author of Tarzan, penned copy for the catalog. On two separate occasions, paintings by Norman Rockwell graced the catalog’s cover. For a 1927 cover, Rockwell illustrated a young couple perusing the catalog, searching for an engagement ring. 1932 was the bicentennial of Washington’s birth, and was the inspiration for Rockwell’s second Sears work. The painting was featured the same year, and was titled, At Work on his Washington Essay. The cover shows a boy, hard at work at his desk, while a stoic George Washington stands proudly in the background.

For some, however, a pen and brush were not necessary for the honor of appearing on the Sears catalog. Actresses Gloria Swanson, Susan Hayward, and Lauren Bacall (and supermodel Cheryl Tiegs) could all be found pictured in the Book of Bargains. 1931 was the first and only time Sears would include paid advertising from some of its vendors, including Chevrolet and Curtis Publishing Company, in their catalog.

A year previous, Sears introduced what some would consider one of its more bizarre products: mail-order chicks, at a cost of 12 cents per bird. When it came to flavor, Sears strove to have a seat at every American’s table, offering exotic items such as Jamaican ginger, fish from Northern Europe, canned frijoles, and pickled pigs’ feet. Mail-order chicks and pickled pigs’ feet, however, could not save Sears’ catalog from being overtaken by its retail sales.

In 1931, even as America was in the thick of the Great Depression, Sears, now synonymous with selling inexpensive necessities, earned more than $12 million. For the first time, the majority of Sears’ sales were not from its catalog, but from its retail presence. Six years previously, responding to changes in shopping habits, they opened their first brick and mortar store in Chicago. By 1929, Sears owned 300 stores nationwide. By the 1950s, Sears’ more than 700 stores anchored shopping malls across the country.

Despite the declining importance of the catalog to its corporate bottom line, Sears continued to offer new and exciting items within its catalog pages. In 1949, the catalog featured TV sets, Hobart dishwashers and Silvertone hearing aids. 1957 brought an automatic garage door opener. In 1971, Kenmore released both a trash compactor and microwave oven.

By the early ‘90s, however, the Sears brand, not just the catalog, experienced a precipitous fall. In 1991, Walmart defeated Sears for the title of the nation’s top retailer. Two years later, Sears closed its catalog division, ending a service once used by one out of every five Americans.

The formal end to distribution of the Sears catalog, however, did not end the legacy of this ubiquitous institution.

Begun in 1933, the Sears holiday book, renamed in 1968 the “Wish Book”, captivated children and adults alike. By 1968, the 87-page original had grown by nearly seven times, to include 225 pages of toys for children and 380 pages of gifts for adults, offering exceptional items such as live canaries. Like any sibling relationship, the Sears catalog and Wish Book could at times be tumultuous and competitive. Special offers were featured in the Wish Book that boasted of savings beyond any found in the main Sears catalog. One Wish Book promoted a washer and dryer set which could be purchased $130 cheaper than the same product in the Sears catalog. Even after the shuttering of the main catalog, the “Wish Book” promoted special discounts beyond those found in-store. In 1998, Sears launched a website where customers could place orders for items found in the physical Wish Book. Sears stepped boldly into the 21st century in 2009, when they placed the entire holiday catalog online, complete with holiday scenes and music. 2011 was the first time in 78 years that Americans did not have a physical holiday catalog to pore over. The Wish Book took one last bow in 2017, when Sears sent out a special issue to customers in its loyalty program.

Although Sears ended syndication of its catalogs, physical testaments to the “Big Book” still remain. One of the grandest fossils of the Sears catalog is its kit homes. It is difficult to locate the tens of thousands of Sears homes sold, due to the destruction of records and the homes being neglected, renovated, and torn down. However, there are small but impressive grassroots efforts that have identified nearly 50,000 delivery homes from Sears and its competitors. One such kit-home crusader, Rebecca Hunter, set out into her neighborhood in Elgin, Illinois with a Sears catalog in hand. Shortly, she spotted her first Sears home. On her subsequent walks she found more and more homes. To confirm her findings, she sent mailers to her neighbors, asking them to check their homes for identifying marks – part numbers, shipping labels, and even blueprints were found. Since the start over twenty years ago, she and her fellow house hunters have identified over 200 homes in Elgin alone.

Since the Sears catalog was a large part of the American experience, there is a market for them—albeit a small and weak one—as antiques. Sears’ massive distribution means supply exceeds demand; Sears catalogs can be priced well under $100; older editions can fetch a higher price. Despite their relatively small monetary worth, the Sears catalog will always be an invaluable part of American culture.

About the Author: Ian Moody is a freelance writer living and working in Philadelphia. He is available for assignment at ianmoody93@gmail.com.

Related posts: