An essay from Quiltindex.org by Merikay Waldvogel

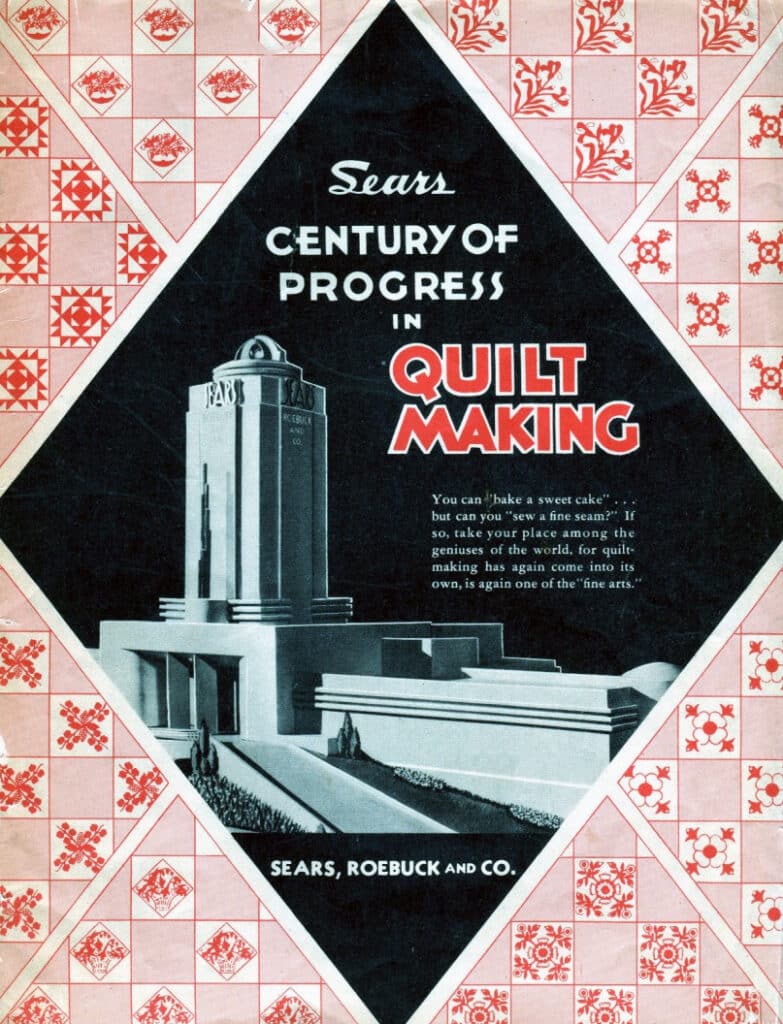

The Sears National Quilt Contest organized by Sears Roebuck & Co. in connection with the Chicago World’s Fair (known officially as “The Century of Progress” Exposition) was announced in the January 1933 Sears Roebuck Catalog. They offered $7,500 in prizes – including a grand prize of $1000.

Why is this contest so important to quilt historians? Because more than 24,000 quilts were entered making the Sears Contest the largest quilt contest in history. Nearly 80 years later, the record still stands. By offering such a large prize when the nation’s economy was not good, the company set in motion a huge amount of quilting. People who had never quilted before decided to try. Husbands and boyfriends helped make the quilts. Adept quilters did their very best work. Local Sears stores not only sold fabric, supplies, and patterns, they displayed the finished quilts. The effects of the contest were long-lasting.

The contest instructions were simple. Enter a quilt “all of your own making” which had not been exhibited before. Sears did not want an exhibit of “antique quilts.” Sears offered quilting advice at their stores. The contest was advertised through the Sears catalog, on a WLS radio broadcast, and in local newspapers’ Sears advertising throughout the nation. At the time, Sears Roebuck was headquartered in Chicago and owned the WLS radio station. Other Sears staff based in Chicago were: Sue Roberts, the contest organizer, whose signature appeared on all the letters sent by Sears to the quilt entrants and Mae Wilford, who served as the quilt advisor in the Chicago area Sears stores.

The quilters had just four months to finish their quilts. The deadline was May 15 for the first round of judging. The top three winners at the local round were sent to one of the ten Regional Mail Order Houses for another round of judging: Boston, Philadelphia, Atlanta, Minneapolis, Chicago, Memphis, Kansas City, Dallas, Seattle, and Los Angeles. At the Atlanta regional round, for example, there were 1100 quilts. Only three from each region were sent to the national round. Of those 30, the judges chose the top three and an Honorable Mention.

Presumably, all 30 quilts were exhibited during the run of the Fair that first summer in 1933. No photographs exist of the quilts on display that summer. There were some publicity photos of the judges with the top three quilts sent to local newspapers. For example, the Lexington, KY newspaper carried an interview with Margaret Caden whose traditional quilt “Star of the Bluegrass” had been awarded the $1000 grand prize.

Commemorative Quilts

Although traditional pieced and appliqué quilt designs won the top prizes, Sears invited originally designed quilts that would depict the spirit of the Century of Progress. They even offered an incentive of $200 if an original design won the grand prize. It is interesting to see how quilters handled this challenge. Some simply embroidered the words “A Century of Progress” across an upper border of a quilt made from a standard pattern. Others spent many hours in the library researching inventions and technological advances to include in their quilt designs.

Chicago area quilters who took the challenge often incorporated aspects of the World’s Fair itself. The 1933 Chicago World’s Fair commemorated the 100th Birthday of the founding of Chicago. The dates 1833 and 1933 were embroidered, appliquéd, and quilted into the entries. Some included the story of Fort Dearborn and the Chicago fire. It’s important to note that the construction of the Fair occurred during the Great Depression.

The buildings at the Fair went up slowly. The replica of Fort Dearborn was erected early and people were encouraged to visit. Promotional brochures included line drawings of the buildings that were planned. The Sears Pavilion was on the front of the contest brochure and it figured prominently on a number of commemorative quilts entered in the contest.

Unfortunately, only two commemorative quilts reached the final round and neither won the grand prize so the $200 bonus was not awarded. Chicago quiltmakers grumbled that their local and regional judges had not treated the Century of Progress quilts fairly. Ida Stow sent a protest letter to Sears but received only a curt reply. However, in the summer of 1934, the Fair managers decided to open the Fair for a second season. Sears had already returned the 30 quilts. Sue Roberts invited the top 10 winners to send their quilts back to the Sears Pavilion. They also invited Chicago quilters who made commemorative quilts to display their quilts. Sears photographed prize quilts as well as the commemorative quilts. Ida Stow’s quilt was front and center.

The Sears Contest Search

The search began when Barbara Brackman was living in Chicago in the late 1970s. She knew about the Sears Quilt Contest and visited the headquarters to ask about contest archives. They had a few photos and a catalog page listing the top 30 winners.

Barbara decided to try to find all thirty quilters to document their stories and their quilts, reaching out to local newspapers, mentioning the search during workshops and lectures, and writing for a variety of Quilters’ publications. As the word spread, she began to get referrals.

I met Barbara Brackman at the Southern Quilt Symposium in Chattanooga in 1984. A Sears Contest quilt showed up at a Quilts of Tennessee survey day. In 1990, when I wrote Soft Covers for Hard Times: Quiltmaking and the Great Depression, I included a chapter on the Sears Contest as it played out in the South.

Following the publication of Soft Covers, Brackman proposed we write a book together solely devoted to the Sears Contest. We pored through the quilt stories that had been referred to Brackman and chose several for the book. We also renewed our quest for new discoveries.

When the book Patchwork Souvenirs of the 1933 World’s Fair was published in 1993, the list of found quilts totaled 95. An exhibit of the quilts in the book organized by the Knoxville Museum of Art and Smith Kramer Fine Arts traveled to ten museums. With publicity about the book and exhibit, more contest quilts appeared.

When the exhibit tour ended in 1996, more than 150 quilts had been found. Both of us continued to write and lecture about the contest. I even acquired two of my own contest quilts – one via an online auction that still had an entry tag attached and one commemorative quilt I named “A Bird’s Eye View of the World’s Fair Site” also with a tag attached.

The Sears Contest Project for the Quilt Index provided an opportunity to share what we have found. For this project, only the most fully-authenticated contest quilts were selected for this online repository. Quilts with good color photographs received preference, but not all the important quilts had color photos. All the final round quilters’ names are included even though some quilts are still missing. Fortunately, quilts were often photographed for local newspapers. When available, we have used those photos. We also found a written eye-witness account of the quilts on display at the Sears Pavilion in 1933. Dr. William Rush Dunton Jr. visited the display and recorded descriptions that often include the quilt name, pattern, colors, and quilting designs. As of June 2011, 235 quilts were in the database kept by Merikay Waldvogel.

Do you have a Sears Contest Quilt?

Over 24,000 quilts were entered in the contest and we have only found information on a small percentage. We have winners’ names that were printed in newspapers, and of course, the top 30 winners’ names and home towns which were published in the Sears Catalog. The list of known entrants and prize winners is listed on the Quilt Index.

If you have a quilt that has a contest entry tag sewn to it or it has a ribbon attached, this is the best proof that the quilt was actually entered in the contest.

Ribbons are strong evidence that a quiltmaker won a prize in the contest though not necessarily with a particular quilt.

If a quilt has world’s fair imagery, the Sears Pavilion, or the dates 1833-1933 appliquéd to it, it was likely made for the contest.

Merikay Waldvogel is the author of Patchwork Souvenirs of the 1933 World’s Fair with Barbara Brackman, among many other titles on quilting and the many studies she and fellow experts in the field have conducted on the topic. Waldvogel is a 2009 inductee to the Quilter’s Hall of Fame. Waldvogel’s lectures and workshops are her true gifts to people in the quilt world.

The Quilt Index (Quiltindex.org) is an open-access, digital repository of thousands of images, stories, and information about quilts and their makers drawn from hundreds of public and private collections around the world. User tools, such as search and compare, facilitate inquiry and education. The Quilt Index is a digital humanities research and education project of Michigan State University’s Matrix: The Center for Digital Humanities & Social Sciences.

Related posts: