By Judy Gonyeau

It is hard to shop anywhere that does not have some form of a rewards program in place. Even in the earliest times, shopkeepers looked for ways to keep buyers coming back for more.

The “Bakers Dozen” is considered the earliest form of a buyer’s incentive to buy more, when buying a dozen baked goods meant you would actually get 13 – the extra often turning into a quick snack on the way home from the bakery. This practice and others were meant to infuse trust and build loyalty to a shop and its products.

The first instance of trading a token for products took place in 1793. A merchant in Sudbury, New Hampshire handed out copper tokens with each purchase. Once the customer collected a number of these tokens, they could redeem them for “free” goods in the shop. This caught on quick, making the 19th century the era of the incentives to keep shoppers coming back again and again.

In 1851, the B. A. Babbitt Company started including certificates in their Sweet Home laundry soap that could then be traded in for color lithographs. The Grand Union Tea Company issued cardboard tickets to shoppers at Cyrus D. Grand Union stores, which were redeemed for merchandise featured in a company catalog.

Sound familiar? It should, because one of the most successful incentive programs offered by grocery stores was built on this very idea: S&H Green Stamps.

Start Licking Those Stamps!

Using stamps as a verified token to collect and trade for goods was first used by the Schuster and Company department store in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 1891. The “Blue Trading Stamp System” was the blueprint for what would become Sperry and Hutchinson Company. Schuster gave a stamp to a customer for every 10¢ spent and provided booklets to paste in the stamps. Customers then traded in their stamp books in for selected products in the store.

The success of the Blue Trading Stamp System was incredible, and caught the eye of Thomas A. Sperry, a silverware salesman from Michigan doing business in Milwaukee. Using his perspective as a salesperson, he theorized that an independent incentive program could be used by a number of shops. The program would be able to expand among a variety of merchants within any given town. Expansion could be swift and territories would be thick with sales potential. The program would automatically build the brand of the trading stamp company and act as a magnet for shoppers always looking to get “something” for “nothing.”

Sperry found a financial backer for this concept in Michigan businessman Shelly B. Hutchinson, together forming Sperry & Hutchinson in 1896. Similar to the Schuster program, S&H sold the right to participate in its program along with the stamps to stores and then provided the premiums either through a catalog or at a redemption store. The more stamps needed to trade for a prized item, the more shopping that had to take place first, driving customers to participating shops for more and more stamps.

First called “Sperry Green Trading Stamps,” Sperry and Hutchinson started issuing the stamps its first year of operation in Sperry’s hometown of Jackson, Michigan. As the company’s salesperson, Sperry moved quickly throughout the territory and expanded to New England where several dry goods businesses bought into the plan, and things really took off. In 1897, the first S&H redemption center opened in Bridgeport, Connecticut, and by the early 1900s, shoppers across the East and Midwest were collecting and redeeming their S&H Green Stamps.

Almost from the very start, labor unions, trade associations, and even politicians turned against the independent incentive industry, mainly because it interrupted loyalty programs at larger chains and made the “Mom and Pop” shops more competitive. The anti-stamp lobby tried to alert shoppers that while it appeared like they were getting a “free” reward by shopping at particular stores, they were not getting a great price on their purchases. Their reasoning was, and it was not entirely untrue, that the store had to pay for the stamps and passed that cost along to the shopper with higher prices on their goods. Merchants also spoke up saying if all the competing shops in a town offered trading stamps, the only business benefiting from the program is the stamp company and not the shops, themselves.

These arguments and more questions continued to plague the industry even as it approached its strongest period of operation from the 1950s to the 1970s. Legislatures in several states fought for laws that would tax the industry with additional penalties for manipulating the market, or sought to ban them completely. When the programs attempted to go into Canada, they were immediately banned from doing so.

Over half of the states in the U.S. introduced anti-trading stamp legislation in the 1950s alone. In 1957, the Federal Trade Commission conducted an investigation that pointed out that, while the trading stamp companies were not considered illegal, they would be keeping an eye on them just in case.

S&H worked diligently to keep these problems at bay. In one instance, the state of Tennessee was trying to double the $300 privilege tax on stamps and add a two percent gross receipt tax on the merchants that gave them out. S&H recruited a number of women’s clubs to lobby the State and to do a mail campaign resulting in over 2,500 pieces of mail delivered to the State House every day. The tax bills were defeated. In return, S&H made very healthy “contributions” to the clubs’ treasuries. This happened in many states looking to ban the program altogether.

In 1968, a complaint was brought against S&H Green Stamps focused on the guidelines the company held their clients to when it came to how they could dispense stamps to customers (like handing out double stamps, etc.), saying S&H had gone so far as to cancel contracts with stores that had not adhered to these guidelines. S&H wanted to control how many stamps were handed out in order to be able to sell enough stamps to cover the costs of the premiums and ensure a tidy profit. Only one stamp could be given out for every 10¢ spent. Shops felt that they should be free to dispense the stamps any way they wished since they were purchased and therefore considered their property.

“The foregoing acts, practices, contractual provisions, and understandings are all to the prejudice and injury of the public, have restrained and hindered, or have a tendency to restrain and hinder competition unduly, thereby constituting unfair methods of competition and unfair acts and practices in commerce, in violation of Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act.” – Federal Trade Commission decision, volume 73, January-June, 1968; pages 1099-1228.

The result? Sperry and Hutchinson was instructed to “forthwith cease and desist from” forcing its policies onto the merchants regarding stamp distribution. S&H was given sixty days to notify employees and merchants, and get contracts updated and filed. Following an appeal in 1972, the Supreme Court backed up the decision by saying the restriction of giving away trading stamps was illegal. Soon stores competed with one another fiercely, offering double and even triple stamps to shoppers even as their expenses increased when buying more stamps.

The sweetest time for S&H was in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. The post-war era saw the birth of the boom in building the modern home with its modern décor, appliances, accessories, fixtures, and more. All those items for the home could be found at S&H Green Stamp stores and catalogs.

As happens when the going gets good, competition against S&H grew, with major companies marketing their own stamp programs. In California, A&P, Safeway, and a number of other businesses joined forces and essentially blocked S&H from getting a foothold in their territory by offering Blue Chip Stamps. Although once investigated by the Justice Department as a possible monopoly in the region, the Blue Chip Stamps had the highest redemption rate of any of its competitors, including S&H.

But S&H was across the U.S. by this point, and the variety of shops handing out stamps—from funeral homes to gas stations, car rental companies to drug stores—made it easier than ever to get and save S&H Green Stamps. It is said that over 80% of American households collected S&H Green Stamps at this time. By 1964, statistics showed that S&H was printing 32 million copies of its catalog, distributing over 140 million savers books, and customers redeemed more than a billion stamps a week, making S&H stamp production almost three times higher than the U.S. Post Office.

A Wave of Consumerism

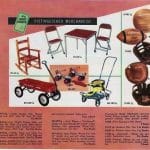

After all that shopping, consumers would lick stamps and try to make a decision on what products to save for, as the Ideabooks offered all the products that could be found at major Department Stores. The question was, who could resist trading stamps for a new blender or living room set or even fine jewelry?

Manufacturers of these items approached S&H to test market new products and sell out large quantities of inventory as well as create buzz around their products, and they were loyal. One of the first items offered back at the turn-of-the-century was a Bissell carpet sweeper, with its more updated version available 100 years later. At its height, S&H was the largest distributor of GE products in the U.S. Product names of everyday items included Melmac, Libby, Corning, Pyrex, Panasonic, Swank, Rubbermaid, Magnavox, Sunbeam, Spaulding sporting goods, Vendome jewelry, Seiko watches, etc. – a veritable who’s who of product names and dictionary of items that were considered the “must haves” of the modern home.

The marketing prowess of S&H to offer modern products from a variety of manufacturers, with the constant issuing of new catalogs and changeover of inventory at their shops, created the buzz that kept driving shoppers in for more.

As I was putting this article together, my mother told me that two of her friends took lessons on how to play Bridge thanks to S&H Green Stamps. Cooking classes, home repair, interior design, and even fine art lessons were available depending on where you lived and what was in demand. The selection seemed endless.

Things were running like a fine engine until the mid-1970s. The economy slowed, the oil crisis gripped the nation, and saving money to stay financially afloat became a focus for the majority of households. Trading stamps seemed to no longer apply when it came to saving dollars and cents – the actual cost of goods played a larger role than saving for that new blender; the old one was working fine. S&H felt the pinch.

And Now?

In the latter half of the 20th century trading stamps struggled to survive. Stamps turned into cards turned into digital points turned into changing hands over the past forty years. Currently, the business is owned by Anthony Zolezzi, CEO of Twinlab Consolidated Holdings, Inc. Zolezzi is a change agent in the world of health and wellness and the environment. Although he was hoping to breathe new fire into the S&H incentive program, initially scheduling a launch for Earth Day in 2015, that did not happen you never know what the future holds, as Zolezzi is an entrepreneur with vision and definitely one to watch.

When it comes to collecting, it may appear there is little to collect other than memories of trips to the store to gather stamps and the taste on your tongue when being allowed to lick the stamps and place them in the saver books. But today, a quick google search for S&H will bring up not only the stamps themselves, but those great catalogues with their images and history. That set of Pyrex mixing bowls that are currently valued at over $150? They may have been bought with a few books of stamps right out of the S&H catalog. Can’t quite figure out what that vintage design on a set of Libby glasses is? It may have been an exclusive design offered only through S&H. Anyone interested in Mid-century Modern would do well to collect the many vintage catalogs for their style and information.

S&H also had great signage both at its participating stores and their own. A double sided lit sign can range from $100 to $1,500 depending on size and condition, but tin signs can go for as low as $75 if you are in the right venue. Signs were often created with both the S&H logo and the name of the store, so the variety is endless.

S&H also produced promotional items from pens to ashtrays to bottle openers and key chains. There was an S&H insulated cooler selling on eBay for $49.95, an ashtray for $14.99, and unused stamps and filled books for anywhere from $5 to $100 depending on the lot. I also came across a rare S&H Green Stamps 25-piece flatware set new in the box for $99 and a Stamps Roller for $42. A 1959 print ad was on Etsy for $8.99.

Catalogs and Ideabooks are also collected and used as reference materials and memory-joggers. Condition is key, and certain years of catalogs sell better than others including their Diamond Jubilee catalog from 1956 (selling for $80+ online). Also look for special catalogs and advertising featuring Dinah Shore, Andy Williams, and Dick Clark; S&H were regular sponsors of their television shows, and these are highly sought after items.

Great graphics and solid marketing made S&H Green Stamps successful, but the taste of those stamps and joy of filling up a book to get a special gift made great memories.

Related posts: