Pressed Glass as Patriotism

Daniel Jay Grimminger, Ph.D.

Since at least the 1820s, North American memorabilia has appealed to the patriotic spirit by portraying the presidents who Americans so dearly loved. Manufacturers of material goods charmed the working class-especially the women, who had control over their parlor rooms that “overflowed with store-bought mass-produced objects, carefully arranged …” These items distributed to the American public were vast. By the time this industry reached its climax in the 1896 election between William McKinley (1843-1901) and William Jennings Bryan (1860-1925), presidential artifacts included “banners, pillows, plaques, tapestries, belt buckles, bandannas, shirts, watch fobs, canes, paperweights, ashtrays, cigar holders, match safes, mugs, plates, trays, bracelet charms, spoons, rings, soap ‘babies,’ razors, mirrors, and other items bearing the names or likenesses of the Republican and Democrat standard bearers.” Out of all of the thousands of presidential mementos, pressed glass has remained one of the most coveted for its clear and beautiful portrayal of the commanders in chief and the nationalistic attitude that they inspired.

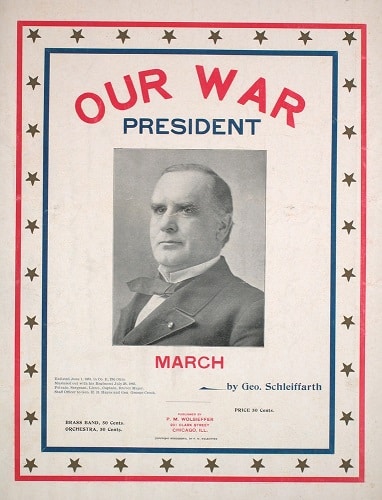

Scholars have defined Nationalism in various ways, but one can say that Nationalism (or what we will call “patriotism” here) is an attitude that raises one’s country and national identity above other countries and other personal identities. One’s country takes on an ultimacy that surpasses other interests and allegiances. This attitude was expressed in so many distinct aspects of material culture in America, including music. Patriotism is a thread that runs throughout American sheet music, which countless Americans bought to create a patriotic spirit in the Victorian home, both aurally-through the realized music-and visually-through the colorful covers. The 1,476 pieces of patriotic American sheet music printed between 1820 and 1916, in the Lester Levy Collection of sheet music at Johns Hopkins University, bears out this claim. The covers are as patriotic as the lyrics of the songs. One such piece, titled “Our War President March” (1898), includes a portrait of President William McKinley on the cover, framed by a blue inner border, a row of gold stars, and an outer red border. Any way that manufacturers could appeal to the American public’s patriotism they did. This was often done by a marketing strategy, which targeted women. The products aimed at women at the end of the nineteenth century were an “influential factor in determining how their husbands would cast their votes.” Thus, presidential glass was more than something that was meant to look pretty. It worked together with other furnishings to “create an American atmosphere” in the home. More importantly, it was an influential force in the overall politics of the age.

Campaigns and Memorials

Pressed glass depicting a president or presidents (“presidential glass” in this essay) was so successful because companies created and marketed their wares at two key times: during a presidential campaign or election year, and when a president died. These were both times when, even if the country was mourning, the patriotic spirit would be high. At both times, the American people came together for the good of the country, something that is seldom seen today. Campaigns/elections and funerals were events that brought people together and glass was a way to memorialize the event and give the parlor room in the home a place in venerating America’s national heroes.

Early examples of presidential glass are sparse, but exemplars exist in curated collections. One such early piece is a cup plate pressed for the campaign of William Henry Harrison (1773-1841), who would become the ninth President of the United States, elected in 1841. Harrison served the shortest term of any U.S. president, because he died just 31 days after his inauguration due to pneumonia. His log cabin cup plate and five other cup plate designs (two with variants) aided Harrison in his campaign efforts. They would have likely served the second purpose of presidential glass (i.e., memorializing the President) following his untimely death.

Unlike other presidential glass, the Harrison cup plate does not include a bust of Harrison anywhere on the piece. But, anywhere there is a meaning, there are symbols. This is as true in music and paintings as it is on pressed glass. The log cabin along with the hard cider barrel, the coonskin, and the liberty pole, were symbols of the Whig Party, but they became “the principle emblems of the [Harrison] campaign and embodied almost every material used by craftsmen.” It is interesting to note that the only place where one finds more designs concerning the presidents and other patriotic subjects in pressed glass outside of cup plates is on flasks and bottles, as George and Helen McKearin demonstrate in their monograph, American Glass.

On one bread plate in a collection, symbolism is particularly pungent. Pressed in 1881 as a memorial to President James A. Garfield (1831-1881), the three busts of Presidents Garfield, Washington (1732-1799) and Lincoln (1809-1865) are surrounded by a garland of leaves, topped by the words “In Remembrance,” and squarely centered around a shield bearing the stars and stripes of the flag. A scrolling banner under the deceased presidents boldly proclaims “God reigns. First in Peace. Charity for all.” This presidential glass bread plate (12 1/2″x10 1/8″) not only memorializes the most recently deceased president for whom the piece eulogized, it pulls on the collective memory of the American people, and makes them remember possibly the most beloved of all presidents up to that time. Garfield, like Harrison, served a short term. Less than four months after his inauguration, a Charles J. Guiteau shot him twice with an English bulldog pistol, disabling him until his death just over two months later.

Another memorial piece was pressed in remembrance of President Garfield. The large round plate (11 1/2″ in diameter) would have gone very well in a parlor room display with its dainty swags akin to a floral damask cloth found in curtains of the age. President Garfield, center, is surrounded by the date he was shot, the date he was born, and the date he died, and a full circle of stars. In bolder, larger letters, the plate states its real purpose: “We mourn our nation’s Loss.” The line wraps around the presidential bust and finds its final punctuation in a larger, lone star.

Two later examples of presidential glass serve as exemplars of the two types I detail above. The first is a small campaign plate from 1896. It bears the bust of McKinley in the center and he is surround by raised stars, as if the stars revolved around him as the center of the universe. McKinley’s bust is in a shield, exactly like the shield in the three-president Garfield bread plate I discuss above, implying that McKinley IS America. His story and his message are the American story and the American message. The point of the shield points downward to the motto “Protection and Plenty,” an illusion to the Republican stance that protected the gold standard. One recent writer comments on the issue at hand during McKinley’s campaign: “the Democrats stand for unlimited coinage of silver to expand the currency against the Republican pledge to maintain the gold standard. Inflation against sound money. Underlying it all was a deeper conflict-the agrarian West and South opposed to industrial East; the ‘toiling masses’ against the ‘special interests,’ as the Democrats put it.” Because of this plate’s diminutive size (7 1/2″ in diameter) it would have been a moment that could be displayed anywhere in the parlor.

The more commonly-seen oval bread plate (10 1/2″x8″) bearing the full figure of McKinley is a memorial piece. It would have been an accompaniment to the pictures Americans saw in their local newspapers of the funeral procession that led up to the Stark County Court House in Canton, Ohio, where McKinley had once practiced law, and where his body laid in state before being interred in West Lawn Cemetery in Canton.15 Somehow, this plate gave Americans another glimpse of the President, something the pictures did not allow for with a closed-casket procession.

The hay day of presidential glass finally came to a close in the second decade of the twentieth-century. Historian, Roger Fischer, explains: “The ceramic and glass decorative objects that filled bric-a-brac cabinets of Victorian partisans remained very much in vogue through the 1908 campaign, declined perceptibly in 1912, and were virtually nonexistent in 1916.” One explanation for this fact is that the Victorian aesthetic gave way to new tastes. In his book on the history of house interiors since 1700, Steven Parisienne writes that “the modernists of the twentieth century followed Nietzsche in reckoning that over-attention to the past turned men into impotent spectators … The brave new Modernists of the 1920s based their design on the two concepts that had dominated the thoughts of the Arts and Crafts designers of the turn of the century: technology and health … Modernism seemed to require designers, at least, to deny an interest in aesthetics and, at most, claim that the form of their work was reliant solely upon function or programmed.” This meant that while the parlor room was still a part of many modern homes, the content was reduced down and the visual appeal was based more on simplicity. This shift also effected the glass companies as they wanted to keep up with the desires of consumers.

Another explanation is that the pressed glass industry was damaged by manufacturing issues and competing fads in the market. Bill Jenks and Jerry Luna, in their layman’s guide to pressed glass, remark: “Torn by labor troubles, the depletion of natural gas, and the depression, the 1890s was a time of turmoil in which many factories were forced to close or combine in an effort to survive …” The period from 1895 to 1915 saw the slow waning of pressed glass in favor of a cut-glass fad, creating a “reversal of public demand” from what it was before 1895 when pressed glass demanded everyone’s attention. Also the popularity of china and pottery around 1900 made glass companies scramble, looking “to other fields for sales potential.”

Even if these facts are in question, we should be asking why pressed glass fell out of favor as a form of presidential memorabilia. One scholar believes that it is entirely for political reasons: “The gradual extinction of one whole group of campaign objects was caused neither by new technology nor by changes in popular tastes, but by a basic transformation in the political system itself … presidential campaigns evolved steadily into highly centralized operations … the most creative aspects of material culture in American politics came to an end.” A more balanced approach may take all of these factors into consideration to understand why presidential glass was only known to later generations in what they inherited from their mothers and grandmothers. Nevertheless, these remnants of a former time have served as constant reminders of the American spirit, the attitude that fueled industry and won wars, created pride and brought unity to the melting pot.

Conclusion

Related posts: