By Judy Gonyeau, managing editor

In the early 1800s, tin peddlers were out and about selling their wares to the westward-leading people of the United States. Soon after, the tin peddler’s role became much more than selling tin; they recycled goods to feed the growing industries in the Northeast and brought news, finished goods, and opportunities to make a dollar or two to the outliers putting their stake in the ground to create a home.

Making Tin Goods in America

There was and still is no tin to be found in America, but there was plenty of iron for making tinplate. England had tin and needed iron to make tinplate. So, as the French and Indian War (1754-1763) was revving up, England imported iron from the Colonies but discouraged them from manufacturing finished wrought iron goods and tinplate, forcing the Colonies to purchase finished goods from England. This remained the law until after the Revolutionary War.

The First Peddlers?

In 1740, prior to the Iron Act, two Irish immigrants by the name of William and Edward Pattinson were importing sheet tin from England to make utilitarian tools for their home in Berlin, Connecticut. The sheet tin was expensive, but these simple products were lightweight and easy to make allowing the pricing to stay low.

After their home market had been supplied, the Pattinson brothers began traveling by foot to other nearby settlements carrying their goods on their backs. This was the kernel of the idea for the traveling peddler. Other families in Berlin began to make tinware and travel to other areas to sell their products. Soon enough, they were going by horseback and, where roads were being made and improved, with wagons.

Traveling Men

It only took a handful of tinsmiths (also called “whitesmiths”) to make enough product for several peddlers to distribute across a wider and wider area. These peddlers were not roaming independent ne’er-do-wells. In the early 1800s, they were hired by the tinsmiths and sent out to sell their goods along the early frontier and then report back to give the tinsmiths the money they were paid for the goods, settle up accounts, restock, and hit the road.

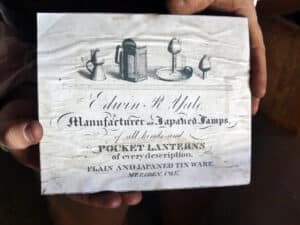

Typically, the peddler would carry items including candlesticks (one of their best sellers), whistles, pans, lamps, coffee pots, dinnerware, and chandeliers. They would carry at least 60-80 pounds of goods on their backs as they traversed across the area to small towns and homes.

Some of the traveling was able to be done with a horse and sometimes a wagon, but for the most part, the early peddlers traveled on foot. There were no trains, barely any maps, and much of the information about homesteads seeking goods came from word-of-mouth. Long narrow boxes would be balanced on each shoulder as the peddlers went through mud, and dense woods with insects and wild animals, Native Americans who may or may not welcoming, and any number of other hazards in all types of weather.

Even though this was not the most enticing of careers for some, many of the young men taking on the task came from across New England where industries were starting to take over the farms where children would have been working.

On the plus side, peddlers would establish a route and work with their customers to get a meal or even a place to stay overnight before going to their next destination. Some even bought land for a future home and met lifelong friends.

The number of peddlers on the road grew as the tin business began to network with other industries. The major factor in the growing number of peddlers was the growing population of the U.S. The population from the end of the Revolutionary War to 1800 had just about doubled from 2.8 million to 5.3 million. By the end of the War of 1812 (1812-1815), it had grown to around 8.7 million people. More people expanding to the Midwest, more people needing household and other goods, and more peddlers out there supplying goods made by their suppliers.

From Peddler to Recycler and Re-user

As other industries started to boom in the early 1800s, Tin peddlers worked to diversify what they sold along with what they were looking for in payment. Tinsmiths often networked with other businesses to enhance the supply of goods and raw ingredients they could sell to the companies via what was gathered by their peddlers. Peddlers were given a list of what was acceptable as payment and the value therein, and the Tinsmiths would use these goods to sell to other businesses as raw materials or needed products.

Buyers/negotiators (almost always the woman in charge of the household) were able to trade any scrap metal, leather, fur, cotton, moonshine, produce, scrap metal or broken metal items, and rags. As an example, the rags were valued at 3½ cents per pound according to an 1854 ledger from Morillo Boyes, a successful wholesaler and scrap trader in Bennington, Vermont. Rags were collected by peddlers because they were used in making fabric and in the huge industry of papermaking. At that time, cotton and rags were used to make paper. Damaged or scrap metal would be recycled to make new items.

And, as the sales territories grew, Tinsmiths would set up a “branch office” in many hubs in cities such as Richmond, Charlestown, Albany, and Montreal. Peddlers would hand over traded items, re-stock, place orders for customized pieces, and get right back out there to their customers with finished goods and maybe sell a few other things.

Show Me Your License

At the turn of the 19th century, there were eight licensed peddlers in Virginia. By 1831-35, that number had increased to 824. New England states were also licensing peddlers in ever-growing numbers. Licensing not only helped to verify who the peddler was but also provided a way for the government to keep track of and make a fee from each license issued. As the number of licenses granted grew, there was some dissent amongst legislators from state to state, saying the peddlers “stole” business from their citizens. At one point, a Kentucky legislator put forth a bill to raise license fees in 1819 because peddlers traveling there from New England kept growing in number.

Contracts also were put together between the Tinsmith or company and the peddler. A typical contract would require the peddler to take inventory to sell “on credit.” Some also gave the peddler a horse and maybe a wagon to transport goods. There might even be a small stipend for expenses. In return, the peddler had to come back with all the funds and trade items to the company which would then be added up and put against the cost of goods acquired by the peddler before they left for their latest trek. Often the peddlers were told to sell everything – even the horse and cart. Any profit could have been shared with the peddler instead of a salary, or taken in total by the company, and then a stipend that had been negotiated ahead of time would be paid.

A Reputation Tested

The use of peddlers as salesmen included several companies as other businesses saw this method as a prosperous way to sell their goods. The peddlers were known for being shrewd businessmen as their jobs changed over time. These Yankee Peddlers also gained a reputation for being a bit too harsh on their customers as rumors of theft and trickery spread.

In the academic paper The Unappreciated Tin-Peddler; His Services to Early Manufacturers by R. Malcolm Keir, “Some of the great industries of which New England is so justly proud have ceased to remember that they owe their start to the humble and even despised peddler. Because the peddler in his zeal for a bargain often used trickery (for instance, he was guilty of selling hams made of bass wood, cheeses of white oak, and nutmegs of wood), that is the thing on which his reputation rests, and not the real service he rendered to the struggling industries of his day, by disposing of their products.”

In another reference (Jack Turner, Spice: the History of a Temptation), it was noted that “Legend has it that unscrupulous spice traders of Connecticut conned unwitting customers by whittling counterfeit ‘nutmegs’ from worthless pieces of wood, whence the nickname the ‘Nutmeg State.’ […] the term “wooden nutmeg” became “a metaphor for the fraudulent or ersatz.”

The term “Yankee Peddler” became a synonym for a deceptive person trying to rip off customers. Rumors spread faster than compliments, and so many of them were unfounded. There were not many peddlers who were truly deceptive. The vast majority did their best to stand by their companies and their customers.

The Decline of Tin

The tin manufacturing industry was often thought of as “too simple” to be a force of industry. Steel was the next great metal. The railroad made it faster and easier to get goods to market. The Industrial Revolution meant machinery was taking away many earlier maker’s jobs. While the bronze market took off (a combination of tin and copper), simple tin and tinplate manufacturing began its downward turn.

Tin manufacturing remained viable in Connecticut until about 1850. However, the network amassed to match companies with customers continues to be used to this day. The peddler may now be represented by company salesmen and associates, as well as automated customer service used online, and the world of AI in its role reaching even the most remote of locations via the Internet to make a sale.

Related posts: