Benjamin Franklin, not an unlikely association,

since as a widely-traveled Postmaster General,

he must have been synonymous with the office

throughout the colonies. Post riders describe a horse and rider postal delivery system that existed at various times and various places throughout history.

The founders knew that delivering mail as quickly and dependably as possible was critical to the colonies’ survival, and after the war, to bringing a nation together. That’s why three months after the battles of Lexington and Concord, the Second Continental Congress on July 26, 1775, established a national post service, known as the United States Post Office, and named Benjamin Franklin its first Postmaster General.

Why Benjamin Franklin?

Prior to his appointment in 1775 as the first Postmaster General of the US Post Office, Franklin had a long association with the importance and challenges associated with delivering the mail.

In 1737, at the age of 31, Franklin was already an established printer and shopkeeper in Philadelphia, and publisher of The Pennsylvania Gazette, when the British authorities appointed him postmaster of Philadelphia. Although the position did not pay much, it came with a big fringe benefit. Franklin had franking privileges, which enabled him to mail his newspaper to readers at no cost. That helped Franklin to turn his newspaper into one of the colonies’ most successful publications.

Franklin, a meticulous record keeper, was so skillful at running postal operations in Philadelphia that in 1753, the British Crown appointed him Joint Postmaster for all 13 colonies. Franklin held that post for more than two decades, most of which were directed by him remotely from England. But Franklin’s involvement with the growing resistance to British taxation and rule eventually caused him to run afoul of British authorities. Carla J. Mulford, a professor of English at Penn State University and author of Benjamin Franklin’s Electrical Diplomacy, notes that Franklin “was rudely and summarily dismissed” from his postmaster-general position in January 1774 after receiving a batch of anonymously sent letters by the British Governor of Massachusetts that were then leaked to a Boston newspaper.

currently hangs in the Oval Office, to the left of the Resolute Desk. The image of Franklin used on the $100 bill is based on the Duplessis portrait.

Franklin’s experience, ideas, management skills, and successes made him the ideal candidate for establishing and overseeing the new U.S. Postal Service, and in July 1775, the delegates offered Franklin the new position of Postmaster General, at a salary of $1,000—about $40,995 in today’s dollars—and authorized him to hire a staff. However, his tenure was cut short less than a year later when he was dispatched to France to perform another important mission on behalf of a new country as an ambassador to the court of King Louis XVI.

The postal system that Franklin helped build continued to flourish and became a critical part of the new democracy. His achievements were honored by putting him, along with George Washington, on the first U.S. postage stamps in 1847.

You can read more about Franklin’s role as the nation’s first Postmaster General, here: https://www.history.com/news/us-post-office-benjamin-franklin.

Philately Gatherings

It was only a matter of time with the issuing of US postage stamps in 1847 that collecting postage stamps and related items would become a thing. Starting with a few enthusiasts in the 1850s, collecting postage stamps as a hobby grew steadily over the next three decades as the US Post Office issued new stamps. By the 1880s, there were an estimated 25,000 stamp collectors in the United States. That number grew exponentially with the issuing of commemorative stamps starting in 1893.

In April of 1886, several prominent stamp collectors with the assistance of some 400 hobbyists formed The American Philatelic Society (APS) as a national organization “… to assist its members in acquiring knowledge in regard to Philately; to cultivate a feeling of friendship among philatelists; and to enable them to affiliate with members of similar societies in other countries.”

Today, APS has members in more than 110 countries and is the largest, non-profit organization for stamp collectors in the world. Learn more about becoming a member, here: https://stamps.org/join-now.

Commemorative Stamps

In 1893, the first U.S. commemorative stamps, honoring that year’s World Columbian Exposition in Chicago, were issued. The subject—Columbus’s voyages to the New World—and the size of the stamps were innovative. The stamps were 7/8 of an inch high by 1-11/32 inches wide, nearly double the size of previous stamps.

Over the years, commemorative stamps have been produced in many sizes and shapes, with the first triangular postage stamp issued in 1997 and the first-round stamp in 2000. In 2017, the Postal Service issued its first stamps with special tactile features — the Have a Ball! Stamps, printed with surface textures mimicking sports balls, and the Total Eclipse of the Sun stamp, printed with a heat-sensitive ink that, when touched, revealed an image of the moon.

The 29-cent Elvis Presley stamp, issued in 1993, has been the best-selling U.S. commemorative stamp to date.

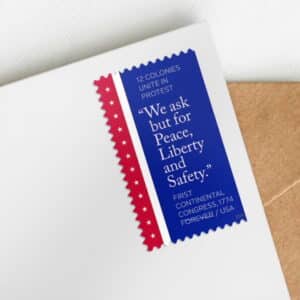

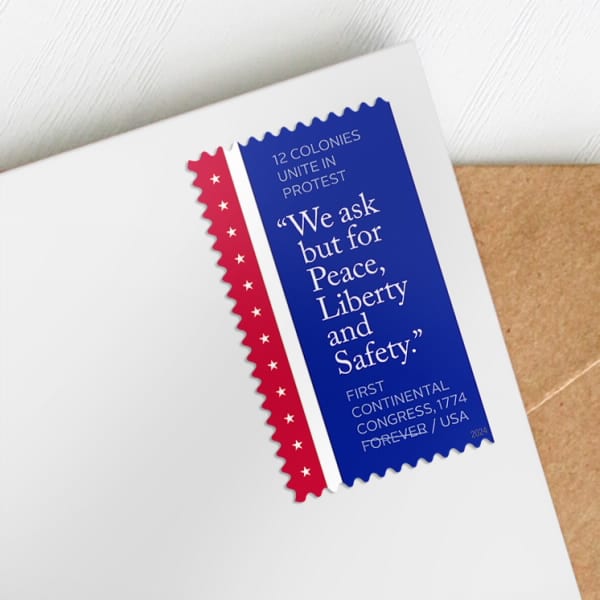

In 2024, the USPS commemorated the 250th anniversary of the First Continental Congress of 1774 with a non-denominated (73¢) forever stamp.

The vertical commemorative features the signature red, white, and blue colors of the U.S. flag. A total of 18 million First Continental Congress, 1774, stamps that were finished into panes of 20 for sale at post offices and other outlets authorized to sell postage stamps, were printed.

National Postage Museum

With a history that dates to the founding of our country, it is no surprise that the US Postal Service has its own museum to house the National Philatelic Collection, among the world’s largest and most valuable stamp collections with nearly six million postage stamps, revenue stamps, and related items, and other postal-related memorabilia to tell its story.

Located in the historic D.C. City Post Office next to the restored Union Station, the Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum was established through a joint agreement between the United States Postal Service and the Smithsonian Institution; it opened its doors in 1993. The Museum showcases the largest and most comprehensive collection of stamps and philatelic material in the world – including postal stationery, vehicles used to transport the mail, mailboxes, meters, cards, and letters, and postal materials that predate the use of stamps. Visitors can walk along a Colonial post road, ride with the mail in a stagecoach, browse through a small-town post office from the 1920s, receive free stamps to start a collection, and more.

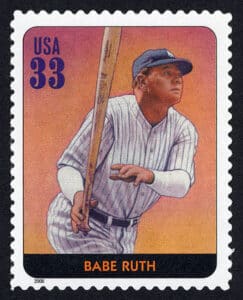

Current special exhibitions include Voting by Mail: Civil War to COVID-19 through February 23, 2025, and Baseball: America’s Homerun through January 5, 2025. Permanent exhibitions tell the story of the USPS through such exhibits as Stamps Around the Globe, World Stamps, Airmail in America, and Gems of American Philately, among others.

Stamp Collectibles

Stamp collectors have a wide range and history of stamps upon which to build a collection. While the value of the hobby is mostly in the fun of completing stamp books and meeting fellow hobbyists, some “holy grail” stamps keep all collectors on their toes.

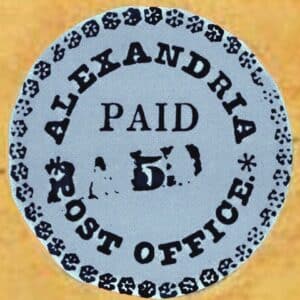

In the world of U.S. stamp collecting, the Blue Boy is akin to the Mona Lisa. Between 1845, when Congress established federally standardized rates for postage, and 1847, when the first federal postage stamps were produced, postmasters in counties and cities within the 29 states issued their own provisional stamps. Postmasters got creative with the designs. For example, the St. Louis provisional stamps display the image of two bears holding the United States coat of arms between them. Of particular interest are such provisional stamps from Alexandria, which were retroceded to the state of Virginia (from the District of Columbia) in these years. Seven such stamps are known to exist, but most of them are “buff” or a brownish-yellow color. Only one of them is bright blue—found on a love letter sent in 1847, that was supposed to be burned by its recipient—earning it the name “Blue Boy,” after the famous portrait—of a boy in fancy blue clothes—by English painter Thomas Gainsborough.

In 1847, the USPS introduced 5 and 10-cent stamps, the first year that you could purchase stamps from the United States government and affix them to a piece of mail as a method to prepay for its delivery (the legislation was passed in 1845). Due to their age and fragility, few in excellent, unused, condition exist today.

Stamp collectors love rarities, firsts, and errors – and 1869 Pictorials with inverted center errors have all three, plus some politics. While the stamps were printed under President Ulysses S. Grant, their issue was conceived in 1868, during the fraught days after Andrew Johnson had been impeached, but still held on to power. Highly controversial and discontinued after one year, these were the first U.S. stamps printed using two colors. The pictorials are also the first example of a printing error by the Post Office Department. To print in more than one color, each color had to be printed separately; the careless placing of several sheets upside down in the press resulted in the first American invert errors.

One sought-after stamp is the 1879-1883 issue 3 cent stamp, thanks to its beguiling blue/green color and its scarcity. Fewer than 20 are believed to exist, of which only 14 have been certified by the American Philatelic Society.

of only two recorded copies

of this rare printing.

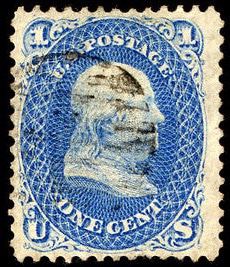

One of the rarest US stamps ever is the “1 cent blue Benjamin Franklin Z-Grill,” of which there are only two recorded copies. One is held by the New York Public Library. That leaves only one one-cent Z-grill available to private collectors. That stamp went up for auction in 2024 by Robert A. Siegel Auction Galleries, selling for nearly $4.4 million.

The Inverted Jenny, though, commands the most attention among collectors. The name refers to a printing error of the original airmail stamp. First issued on May 10, 1918, in which the image of the Curtiss JN-4 airplane in the center of the design is printed upside-down. Only one pane of 100 of the inverted stamps was ever found, making this error one of the most prized in philately.

To learn more about “The 10 Most Valuable U.S. Stamps” from History.com, click here: https://www.history.com/news/10-most-valuable-stamps-in-american-history.

Related posts: