The spies from the earliest days of America may not have had the level of “toys” and methods used by a 21st century James Bond. Still, their tactics and establishing U.S. Intelligence operations are just as fascinating.

The Art of Disguise During the Revolutionary War

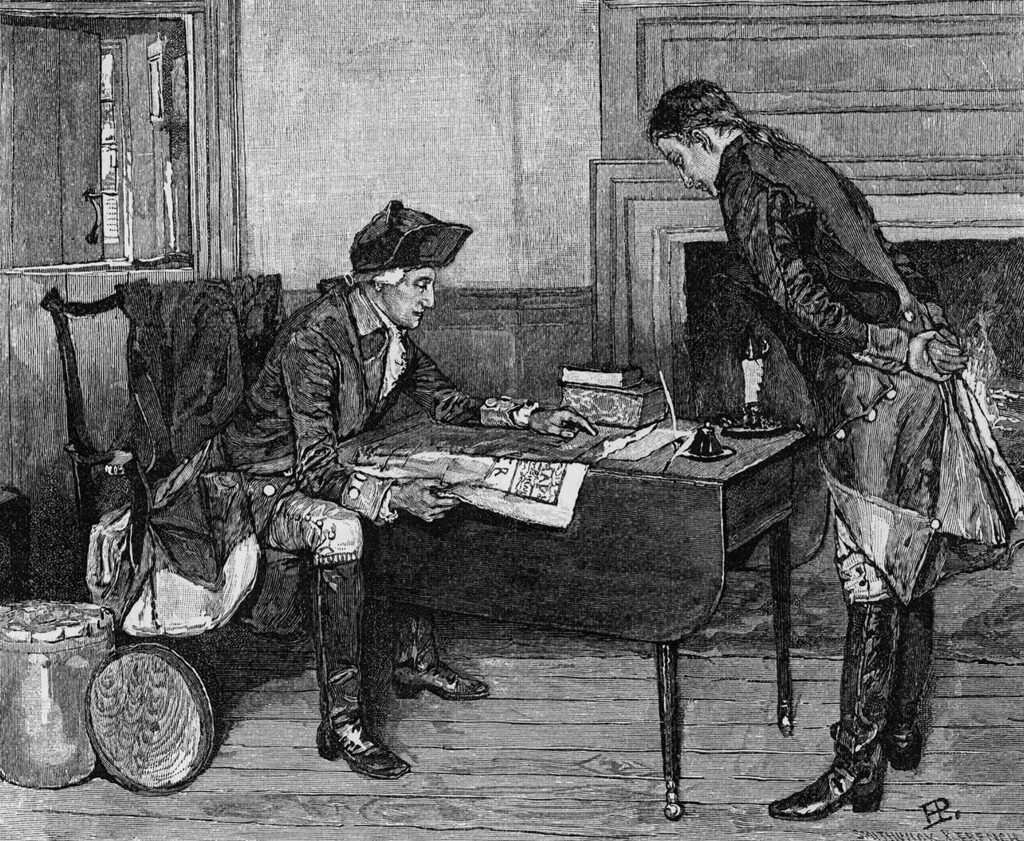

According to MountVernon.org, Nathan Hale used disguises to gain access behind enemy lines. “During the Battle of Long Island, Nathan Hale—a captain in the Continental Army—volunteered to go behind enemy lines in disguise to report back on British troop movements. Hale was captured by the British Army and executed as a spy on September 22, 2776. Hale remains part of popular lore connected with the American Revolution for his purported last words, ‘I only regret that I have but one life to give for my country.’”While a person may dress as the enemy, apply makeup to change their features, or fake a broken leg to go undercover, objects hiding in plain sight were also used to disguise a message. The Culper Spy Ring, headed up by Benjamin Tallmadge during the Revolutionary War, “employed systematic tactics of dead drops, codes were hidden in plain sight (a petticoat hanging from Anna Strong’s clothesline could indicate the location of a meeting or that a message was available at a dead drop), and even messages written in invisible ink with ciphers and coded letters,” as stated at battlefields.org. Even George Washington worked with Tallmadge to use invisible ink to leave messages on pocketbooks and everyday ephemera, including pamphlets or flyers, which were less likely to be searched or confiscated than personal correspondence.

Most of the spies who worked in America and beyond were ordinary citizens doing their bit for freedom. Their unique approach to spying often utilized their personal skills and connections. For example, Patience Lovell Wright, an American-born artist living in London, sent secret messages across the Atlantic hidden in wax busts she sculpted. Wright also corresponded with Ben Franklin and Thomas Jefferson by sending letters inside buttons, in drawings, and through other ingenious methods.

While Quaker Lydia Darragh’s Philadelphia home was occupied by the British, she hid in a small closet to gather information that she would later share with patriots at a tavern in another town. She was never considered a suspect by the British.

Hercules Mulligan was a tailor in New York City and catered to the British and patriots. Thanks to his “interest” and grand service when servicing British officers, he was able to learn when troops were going to be on the move (if they suddenly needed quick repairs to uniforms) and could get messages to Washington and other leaders when concealing them within clothing. His slave, Cato, also gathered information while in the shop and would move information when making “deliveries” to whoever needed to hear all about what transpired.

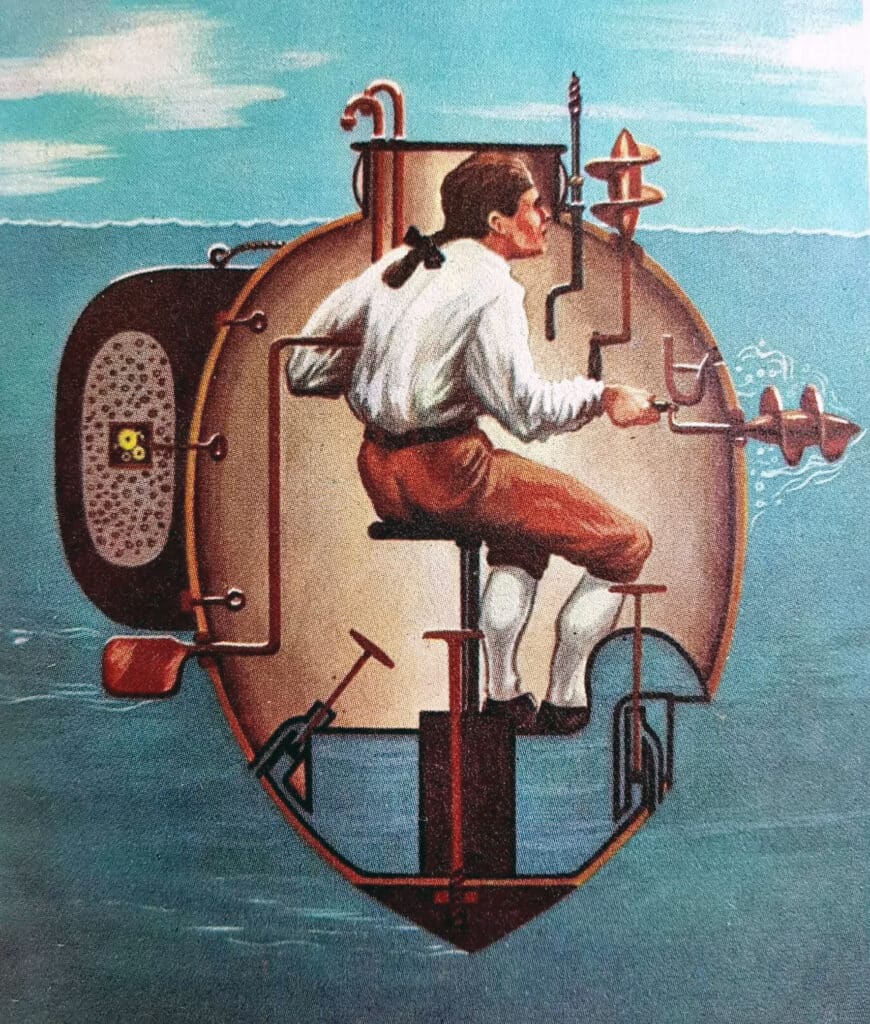

A ragtag colonial army faced the mighty British Empire in 1776. Could American ingenuity turn the tide? Inventor David Bushnell hoped so. Bushnell built America’s first combat submarine, the pedal-powered Turtle. Its covert mission? To slip into New York Harbor and attach a bomb to a British warship. It almost worked. The pilot submerged beneath the ship undetected, but had to abort as his air ran low.

New War, New Spy Methods

Moving into the Civil War era meant several changes were made regarding how espionage was conducted. While some battles were fought as citizens watched from nearby hills or even a distant front porch, the topography of the land and whereabouts of key locations that impacted the slave trade, national and international trade, and government strongholds, along with the movement of troops, were continually monitored using spies working by foot, on horseback, and within the workings of the area’s modern society. “Scouts” were often paid spies and guides for either the Confederate or Union military as they moved across the country and fought in unknown lands and terrain.

The Union Army

According to intelligence.gov, “The United States military hadn’t been involved in a large-scale military conflict for more than a decade, and the small peacetime Army was mostly deployed west of the Mississippi River, protecting pioneers and homesteaders. With the country now at War and the Federal Army suddenly faced with tens of thousands of Confederate troops just across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C., military intelligence became an urgent priority. Options for leading such an enterprise, however, were few.”

One of the most famous names in the world of detective work and spying was Allan Pinkerton. The Commanding General of the (Union) Army of the Potomac, George McClellan, chose Pinkerton as the leader of the Army’s first intelligence organization. The two were past acquaintances—Pinkerton had provided security for the Illinois Central Railroad while McClellan was its Vice President—and Pinkerton was already involved in the Underground Railroad. He had also worked with other detectives to foil a plot to assassinate President-elect Abraham Lincoln, earning him a great deal of respect from McClellan. Pinkerton had a healthy ego and often called himself the “Chief of the United States Secret Service,” even though the agency did not yet exist.

Pinkerton agent Timothy Webster traversed the Southern states, making connections with the Confederate military, including its leaders and generals. He would bring messages from the South to Confederate members in the North but “stop by” Washington D.C., where the messages would be unsealed, opened, read, and resealed before reaching their intended recipient. In April 1862, Webster was arrested by the Confederacy as a spy (much to the embarrassment of its leadership) and was found guilty of “lurking about the armies and fortifications of the Confederate States [while] at the time an alien enemy and in the service and employment of the United States.” Webster was found guilty and hanged.

The Confederate Army

In the earliest days of the Civil War, the Confederate military took advantage of the Union’s lack of a strong intelligence organization by growing their network of sympathizers and spies who worked and lived in the Nation’s capital, Washington D.C. Also to the Confederates’ benefit was having the “home field advantage” of sorts as the War raged on within their own territory, which they knew inside and out. Confederate spies had little reason to infiltrate the unknown northern terrain of the Union-held states. Ultimately, their espionage plans made them feel more secure in the South. Still, the information they gathered had a limited impact on how the Confederates fought.One of the most famous spies working for the Confederacy was Belle Boyd. She had killed a Union soldier after he and his cohorts attempted to raise the Union flag at her home. At trial, her shooting was considered a “justifiable homicide.” As word spread about the incident, she became known as “La Belle Rebelle” in the press. She became a noted spy working with General “Stonewall” Jackson and other Confederate commanders. By then, she had relocated to her aunt’s hotel in Front Royal, Virginia, where she flirted with members of the Union army and took information to her connections.

Boyd’s reputation was shared in both the Southern and Northern press, so much so that the Secretary of War Edwin Stanton issued an arrest warrant in July 1862. Boyd was captured by a Pinkerton agent and held at the Old Capitol Prison in Washington, D.C., only to be released a year later in a prisoner exchange. She moved to Martinsburg, West Virginia, and resumed spying. Caught again, Boyd suffered typhoid fever in prison and was again transferred back to the South.

According to intelligence.gov, “Unable to return to Martinsburg, she traveled to Europe in Early 1864 aboard a blockade runner to escape the War. … After the ship was captured by a Union Navy warship, Boyd Charmed one of her captors, and, ironically, the two fell in love and married. In 1900, at the age of 56, Boyd died of a heart attack while on a speaking tour in Wisconsin.”

20th Century Military Spies: A world at war

During WWI and WWII, the U.S. once again could not establish an international intelligence organization; however, this in no way deterred the work of government and volunteer spies from sharing intelligence in the cause for peace … and wartime spies used what links they had to get the job done.

FBI.gov talks about the FBI during wartime as incredibly busy. “The Bureau had a vital role in protecting the homeland and supporting the war effort – from rounding up draft dodgers to investigating companies that deliberately supplied defective war materials just to turn a tidier profit. The FBI continued performing background checks on federal workers to keep criminals from entering the government. It kept working to head off espionage and stepped up its efforts to gather and analyze intelligence and to feed it to policymakers. The FBI Laboratory, growing stronger and more capable by the year, played a pioneering role by helping to break enemy codes and by engineering sophisticated intercepts.”

Another government office was organized and operated during World War II. America’s continual burgeoning of its international intelligence hierarchy was tried and tested.

In 1908, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) was founded to handle national domestic investigations and espionage, to uphold the law of the land, and to protect its citizens. However, it would take until 1947—after the end of World War II—to establish the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) as the U.S.’s official international arm of governmental intelligence.

World War I

Thanks to the Industrial Revolution, improved communications methods, and modernized armaments, the way wars were fought had more options than ever before. World War I now had battles being won by air, sea, land, and intelligence. As explained at intelligence.gov, “Early in the War, the United States began selling thousands of tons of desperately needed explosives and munitions to what was known as the Triple Entente or the Allied Powers (Great Britain, France, and Russia). Though the U.S. was technically neutral in the War, British naval dominance in the Atlantic Ocean forced American munitions manufacturers’ hands. If they sent munitions to Germany, they would be sunk.” Germany responded by blocking as many deliveries of munitions to the Allied Powers as possible and was successful in their efforts.

Before joining the War, there were battles to be won at home. In 1913, an immigrant from Germany who had graduated from Harvard with a PhD in German traveled to New York City to volunteer in the German spy ring, the Abtielund Illb – Germany’s military intelligence office. While it is unclear what his status was with this group, on July 2, 1915, “Frank Holt” (Erich Muenter) placed explosives in the Senate reception room of the U.S. Capitol. The bombs destroyed the area and also caused damage to the Senate chamber. Muenter then focused on J.P. Morgan, Jr. He went to the financier’s home and shot Morgan twice before he was subdued by Morgan’s staff and then arrested. He was then linked to the Capital bombing, and on July 6, he jumped to his death from his New York City jail cell. The following day, the SS Minnehaha exploded. The ship had been loaded with munitions for France. Captain Tunny, in charge of Muenter’s case, was able to link the bomber to this incident as well.

Another on-shore spy worked against the United States by using germ warfare to destroy Cavalry horses on their way to France, killing thousands of horses. Anton Dilger, a volunteer veterinarian, was recruited by German Spy Franz von Rintelen to pull off this devastation. Dilger and his brother grew cultures in their basement that was used as part of a “health” injection administered to the horses as they boarded ships to make the trip to France.

At this point, not only did the U.S. lack a centralized intelligence organization, but the Army and Navy intelligence operations were underfunded, and resources were lacking for the federal law enforcement agencies as well. Other countries were able to pick up some of the slack. When Great Britain’s intelligence discovered a German plot against the U.S., America entered the War. When Great Britain’s intelligence discovered a German plot against the U.S., America entered the war.

After entering WWI, the U.S. passed the Espionage Act in June 1917. The Act was built on a law passed in 1911 with new elements included to further outline activities that were called dangerous or disloyal, such as acquiring military operations information, photos, books, blueprints, etc., for use against the United States. An amendment was added in 1920 called the Sedition Act, but this was later repealed as it counteracted a citizen’s right to free speech.

World War II

The outbreak of what was to become World War II followed years of radical racial rhetoric and the growth of power-hungry dictators seeking to take over how the world functioned.

For Americans, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the agency in charge of gathering information from around the world. According to the National World War II Museum, then-President Roosevelt “realized the need for some sort of coordination for the gathering of intelligence. He chose General William ‘Wild Bill’ Donovan to be the leader of the Office of the Coordinator of Information (COI) established on July 11, 1941. Donovan was a highly decorated hero of the First World War and was awarded the Medal of Honor, among other orders and medals.”

lighting conditions.

The OSS recruited and trained spies to carry out covert operations, gather intelligence, and spread propaganda to send messages and affect the perception of the enemy in its own territory. Throughout the War, the Office expanded as it added branches and departments, including Strategic Services Operations and Intelligence Services.

According to the National WWII History Museum, “The Strategic Services Operations department, titled Special Operations (SO), was modeled on the British Special Operations Executive (SOE), carried out missions dropping small teams of officers to train and assist resistance fighters, as well as committing acts of sabotage, destruction, and general mayhem.”

Unfortunately, infighting within the OSS and other intelligence and military agencies took its toll. Strategic Intelligence (SI) and Strategic Operations (SO) were at odds with the OSS. “SI’s work in recruiting agents and building networks took a different set of skills and temperament from SO’s work of parachuting into occupied

territory and destroying enemy infrastructure. Some SI officers viewed SO colleagues as trigger-happy hooligans, with the subtle ways of a drunken rhinoceros. Some SO officers viewed SI, especially those operating under diplomatic cover, as nothing more than ineffective diplomats or ivory tower eggheads,” – the National World War II Museum. All this and more contributed to discord and highlighted the growing pains of building an international spy organization.

Noted spies operating on behalf of the U.S. during the Second World War included Josephine Baker, the famous singer and dancer who also spied for French intelligence; Arthur Goldberg, who would go on to become a Supreme Court Justice; and Sterling Hayden, called “the most beautiful man in Hollywood,” who left acting to fight in World War II. Other famous spies included Hedy Lamarr, a glamourous movie star who patented a “Secret Communication System” that helped guide radio-controlled torpedoes to reach their targets; Hollywood director John Ford who created OSS training films and war documentaries; and actress Marlene Dietrich, who not only entertained troops at the front lines during the War but recorded sentimental songs in German for broadcast to Nazi troops.

The scattered and sometimes splintered spies working on all sides of the World Wars continued fighting for improved tools in the field and at home to help keep the peace.

Related posts: