By Maxine Carter-Lome, publisher

In 1820, Thomas L. Jennings (1791–1856) was a well-known tailor among gentlemen of wealth and taste, with a successful clothing shop in Lower Manhattan in New York City. He used the finest cloth and decorative elements to satisfy his client’s desire for quality and refinement.

Preserving His Craft

Jennings found himself disappointed in the conventional methods used to safely clean dirt and grease from his customers’ expensive clothes without soaking the fibers and ruining the fabric. He experimented with different solutions and cleaning agents, testing them on various fabrics until he found the right combination to effectively treat and clean them. He filed a patent for his process of “dry scouring” fabric that same year under the Patent Act of 1793, and was granted U.S. patent 3306x on March 3, 1821.

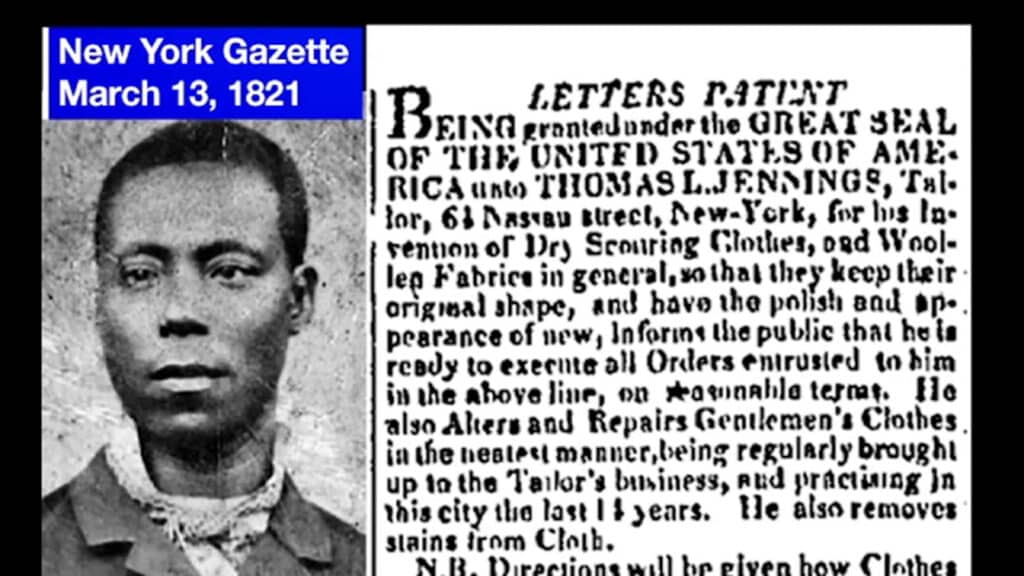

An item in the New York Gazette dated March 13, 1821, announced Jennings’ success in patenting a method of “Dry Scouring Clothes, and Woolen Fabrics in general, so that they keep their original shape, and have the polish and appearance of new.”

According to Emily Matchar in a 2019 Smithsonian magazine article, we may never know exactly what Jennings’ scouring method involved, although it is widely recognized as the precursor to modern-day dry cleaning.

A Patent Earned, But Lost

“[U.S. Patent No. 3306x] is one of the so-called ‘X-patents,’ a group of 10,000 or so patents issued by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office between its creation in 1790 and 1836, when a fire. began in Washington’s Blodgett’s Hotel, where the patents were being temporarily stored while a new facility was being built. There was a fire station next door to the facility, but it was winter and the firefighters’ leather hoses had cracked in the cold.

Before the fire, patents weren’t numbered, just cataloged by their name and issue date. After the fire, the Patent Office (as it was called then) began numbering patents. Any copies of the burned patents that were obtained from the inventors were given a number as well, ending in ‘X’ to mark them as part of the destroyed batch. As of 2004, about 2,800 of the X-patents have been recovered. Jennings’ is not one of them.”

This, however, is not the real story behind U.S. Patent No. 3306x. It’s actually about the patent holder, Thomas Jennings, the first known African American inventor to be issued a U.S. patent, recognizing him as a U.S. citizen and granting him the legal right to own and profit from his invention.

A Question of Citizenship

Although African-American slaves were known to work with their masters to create trade tools and better methods for getting the job done, they were not eligible to file for a patent. The exclusion was based on the legal presumption that “the master is the owner of the fruits of the labor of the slave both manual and intellectual.” They were also excluded by a requirement of the 1793 Patent Act, which contained a “Patent Oath” that required applicants to swear to be the “original” inventor of the claimed invention and a U.S. citizen.

Enslaved people up until the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments after the Civil War were not considered U.S. citizens. Individual states enacted laws that prevented enslaved people from owning any kind of property, presumably including patents. While there were some provisions through which a slave could enjoy patent protection, the ability of an enslaved person to seek out, receive, and defend a patent was unlikely.

“It’s likely that some slave owners secretly patented their slaves’ inventions,” writes Brian L. Frye, a professor at the University of Kentucky’s College of Law, in his article Invention of a Slave. “At least two slave owners applied for patents for their slaves’ inventions, but were denied because no one could take the patent oath – the enslaved inventor was not eligible to hold a patent, and the owner was not the inventor … some black inventors hid their race to avoid discrimination, even though the language of patent law was officially color-blind. Others used their white partners as proxies. This makes it difficult to know how many African-Americans were actually involved in early patents.”

Black inventors who were either born free, like Jennings, or otherwise, who had acquired their freedom, also faced challenges—legal and financial—in securing a patent based on the citizenship requirement and the ambiguous status of free African Americans as U.S. citizens.

The Application

When he applied for his patent in 1820, Jennings was emboldened by his status as a free black man born in New York City to a free Black family. He was also a successful business owner. On the application, he checked off the box declaring himself a U.S. citizen.

The issuing of his patent less than a year later was the ultimate confirmation of his belonging; it officially recognized Jennings as a U.S. citizen. This was a rare designation for a Black person at a time when forces such as the American Colonization Society opposed the right of free African Americans to live here.

Jennings’ patent generated news and controversy, neither of which he seemed to mind. It also made him a wealthier man and someone not to be trifled with. When a rival tailor illegally used the invention, Jennings sued him in the city’s Marine Court and won $50 when he dramatically produced the Letters of Patent.

According to The Inventive Spirit of African-Americans by Patricia Carter Sluby, Jennings was so proud of his patent letter, which was signed by Secretary of State—and later President—John Quincy Adams, he hung it in a gilded frame over his bed.

A Post-Patent Legacy

Jennings spent the first money he earned from his patent on legal fees to buy his family out of enslavement. Jennings’s wife, Elizabeth, was born a slave in Delaware in 1798. Under New York’s gradual abolition law of 1799, she was converted to the status of an indentured servant and was not eligible for full emancipation until 1827. After that, he spent much of his apparently substantial earnings on abolitionist and civil rights causes, earning him even greater distinctions in his lifetime for philanthropy and activism.

In 1831, Thomas Jennings became the assistant secretary for the First Annual Convention of the People of Color in Philadelphia, PA, and went on to found Freedom’s Journal, the first black-owned newspaper in America, and helped to found the Legal Rights Association in 1855, raising challenges to discrimination and funding and organizing legal defenses for court cases.

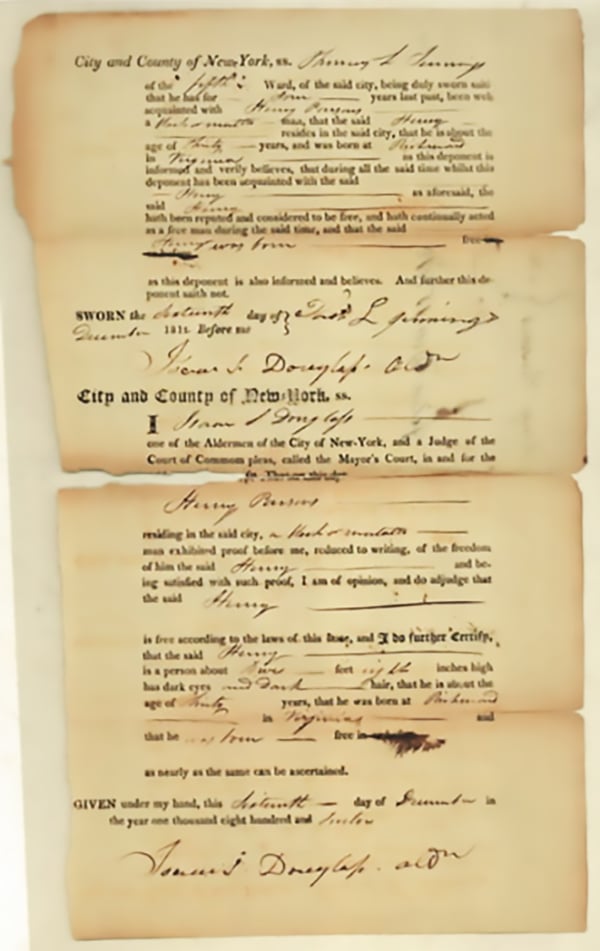

Jennings was also a leader in New York City’s black community. A native New Yorker, Jennings was among the “one thousand citizens of color” who volunteered to dig trenches to fortify New York City during the War of 1812. Well respected and highly regarded, he signed Certificates of Freedom for other black men vouching for their status as free Americans. He was also a founder and trustee of the Abyssinian Baptist Church, a pillar in the Harlem African-American community, and a civil rights activist who organized a movement against racial segregation in public transit in the city.

A Strong Defense

After his daughter, Elizabeth Jennings, a fellow activist, was forcibly removed from a “whites only” New York City streetcar in 1854, Jennings used his wealth to retain the best legal representation for her. He hired the law firm of Culver, Parker, and Arthur to sue the bus company and was represented in court by a young attorney named Chester Arthur, who would go on to become the 21st President of the United States.

Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune commented on the incident in February 1855:

She got upon one of the Company’s cars last summer, on the Sabbath, to ride to church. The conductor undertook to get her off, first alleging the car was full; when that was shown to be false, he pretended the other passengers were displeased at her presence; but (when) she insisted on her rights, he took hold of her by force to expel her. She resisted. The conductor got her down on the platform, jammed her bonnet, soiled her dress, and injured her person. Quite a crowd gathered, but she effectually resisted. Finally, after the car had gone on further, with the aid of a policeman they succeeded in removing her.

Ms. Jennings ultimately won her case in front of the Brooklyn Circuit Court in 1855. The jury awarded her damages in the amount of $225, and $22.50 in costs. The next day, the Third Avenue Railroad Company ordered its cars desegregated. Her father lived to see the outcome of his daughter’s trial but died the following year. It took a decade, until 1865, for all New York City streetcar companies to eliminate segregation on their lines.

When Jennings died in 1856, Frederick Douglass described him as “a bold man of color” who led an “active, earnest and blameless life,” and noted the importance of his patent that recognized Jennings as a “citizen of the United States.”

The epitaph on his headstone in Cypress Hills Cemetery sums up his life in a way that respects Jennings’ greatest contribution to the American story, that of “Defender of Human Rights.”

In 1861, five years after Jennings’ death, patent rights were finally extended to slaves. In 1870, the U.S. government passed a patent law giving all American men including Black Americans the rights to their inventions.

The “dry-scouring” process Jennings invented is essentially the same method used to this day by dry cleaning establishments, worldwide.

The Marketing of Jennings and Dry Cleaning

Sharing the good news about inventor Thomas Jennings and his Dry-Cleaning invention is, and was, a marketing adventure in its own right. Early on it was typically noted in classified and the occasional print ad from tailors and the like. Word of mouth regarding this “miracle” machine and method spread over time, leading to a demand to have this cleaning method available for the homemaker.

According to www.frontiersin.org, “The first dry-cleaning operations in the United States (U.S.) date back to the 1800s when people washed fabrics in open tubs with solvents such as gasoline, kerosene, benzene, turpentine, and petroleum and then hung out to dry.”

To say this was dangerous is an understatement. At the turn of the 20th century, the U.S. started using specialized machines for the dry-cleaning process in order to contain the dangers of the chemicals. In 1911, a book titled The Practical Dry Cleaner, Scourer and Garment Maker became the “Bible” for dry-cleaning shops with the how-to’s and guidelines for running a successful business. It was presented first at the 1911 Convention for the National Association of Dry Cleaners.

There was also a publication for dry cleaners that started in the mid-1800s called the Practical Dry Cleaner and later another called Information that offered ideas, innovations, and more to those involved in the industry. Information was promoted as the “ONLY magazine in the United States that is edited by a practical dry cleaner, dyer, and chemist. All recipes are tried before publishing.” Within its pages were advertisements for Studebaker Delivery Wagons, The Berwyn Steam Dye and Cleaning Works, a classified for a course on “How to Remodel Hats,” and Taylor-Made Garment Hangers.

Individual shops were heavily supported by organizations such as the Neighborhood Cleaners Association. The N.C.A. is an organization of retail, on-the-premises dry cleaners in New York. New Jersey, Connecticut, Delaware, and part of Pennsylvania. This and other Associations that popped up supplied businesses with marketing tools to promote their company and the industry.

In the 1930s, the California State Fire Marshal produced a short film to show in theaters called More Dangerous than Dynamite, showing a homemaker cleaning clothes in a tub with white gasoline, ingesting fumes, her children ingesting fumes, and a fire in which she is horribly burned (showing her covered head to toe with white plaster in a hospital bed) and at the end of the film, is shown to be featured in a newspaper, alive, but “withered and scarred for life.” This tragic story is interjected with industry film showing a state-of-the-art dry-cleaning company with all sorts of safety bells and whistles in place. With the dangers of dry cleaning, businesses took to any way possible to promote the safest way to care for your finest clothing: go to a professional.

As the industry boomed, dry cleaners marketed their message in just about every way possible, including strong signage, advertising, printing on their hangers, on the bags placed over cleaned clothes, and more. Pick-up and delivery, 1-Hour Cleaning, drive-through shops, and more help to keep the industry on its feet.

Still Celebrating Today

In 2018, BeCreative360 (a marketing firm for dry cleaning and other specialty shops) established the first annual National Dry Cleaning Day, a new holiday falling on March 3 of every year. National Dry Cleaning Day celebrates the day Thomas Jennings, an inventor and abolitionist leader, filed a patent for dry-scouring on March 3, 1821. This new holiday, quickly embraced by dry cleaners across the nation, is gaining in popularity year after year, with a multitude of marketing tools and graphics offered for free to dry-cleaners across the country.

Also, an online business called ourhistoryisdope.com is selling a range of casual wear that features Black inventors over time, including Thomas Jennings.

An Excerpt from the Article “Taken to the Cleaner’s”

by Louis Botto in The New York Times, August, 1975

So, where have the likes of the du Ponts, Rockefellers, Deweys, Roosevelts, Harrimans and Lehmans sent their dry cleaning and laundry? These illustrious families, plus Lee Radziwill, Richard Rodgers, Mrs. Gilbert Miller—and when they’re in town—Frank Sinatra, Rex Harrison, Gregory Peck, Robert Cummings and Peggy Lee, have for years patronized the Budge?Wood Laundry Service, Inc., housed in a gargantuan plant in the heart of Harlem.

There, 600 skilled workers toil to do the kind of specialized cleaning and hand-pressing that their fastidious clientele has demanded since the business was founded in the nineteen-thirties by tennis champions Donald Budge, Sidney Wood and Frank Shields.

The current owner of BudgeWood, Alexander Karten, proudly escorts a visitor around his plant, pointing out Rex Harrison’s finely cleaned and pressed shirts, and commiserating over the passing of one of his most illustrious customers—Ari Onassis. “He always sent us his silk shirts when he was in town. He said we were the only ones who pressed them correctly. We charged him $5 a shirt.

“The Johnson used to send us their towels from Washington,” Mr. Karten continues, “and the Kennedys their linen when they were in the White House. F.B.I. agents would come by to check the finished work to make certain that there were no incendiaries in the tablecloths.”

The Budge-Wood name appears only on the Harlem plant and on trucks that pick up laundry and dry cleaning. “We have about 30 shops in New York,” says Mr. Karten, “and one in Connecticut, under such names as Fleur-DeLis and Certified. But all our work is processed in the Harlem plant.”

Related posts: