by Maxine Carter-Lome, publisher

“MOURNING—Court, Family, and Complimentary—The Proprietors of the London General Mourning Warehouse, Nos. 247 and 249 Regent-street, beg respectfully to remind families whose bereavements compel them to adopt mourning attire, that every article (of the very best description) requisite for a complete outfit of mourning may be had at their establishment at a moment’s notice.”

– Advertisement in The Illustrated London News, August 31, 1844

When Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert died in 1861, the world joined the distraught Queen in her mourning. Average citizens of all classes, both here and throughout Western Europe, looked to emulate her piety, dress, and mourning conventions not only as a way to show her their respect but to publicly display their own wealth and refinement in the mourning of their own loved ones in a way once reserved only for royalty and aristocrats.

Prince Albert’s death escalated an already elaborate set of strict protocols that dominated mourning rituals for royalty and commoners alike through the Victorian Era and into the pre-war decades of the 20th century. These requirements were shared with the general public through articles in fashion magazines, mail-order catalogs, and etiquette handbooks that dictated everything from the various stages of mourning to be followed to what one was to wear during each phase and for how long based on the relationship between mourner and the deceased. It also created consumer demand for one-stop mourning shopping, resulting in a booming ready-to-wear industry and the rise of huge department stores in both London and in America known as mourning warehouses.

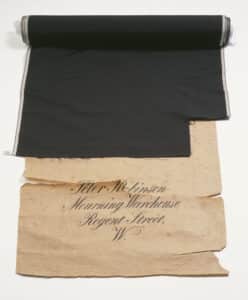

Mourning warehouses provided everything one needed to put forth a socially appropriate display of mourning. This not only included mourning garments and accessories for all sizes and phases of mourning, and fabric with which to drape a home, but also gravestones, coffins, and the ability to rent a hearse and the appropriate horses to draw it. Thanks to the railway and developing technology that allowed for the ready-to-wear mass production of mourning clothing, mourning warehouses were also able to supply customers with proper clothing within a day at rates much cheaper than one’s local tailor or dressmaker.

Companies such as Jay’s London General Mourning Warehouse and Peter Robinson’s Mourning Warehouse, both located on Regent Street in London, and in America, Jackson’s Mourning Warehouse in New York City, and Besson & Son of Philadelphia, sprung up to meet the needs of “sudden” mourners by supplying everything individuals and families needed “to carry out the requirements of Modern Mourning Orders.”

Jay’s London General Mourning Warehouse

One of the largest and most renowned of the Victorian Era mourning warehouses was Jay’s London General Mourning Warehouse, which opened on fashionable Regent Street in 1841.

An entrepreneur and marketer by nature, William Chickhall (W.C.) Jay recognized a business opportunity in the link between grief and clothes, and the public’s need for guidance and easy access to the prescribed items as they navigated the ever-changing fashion and protocols of Victorian mourning.

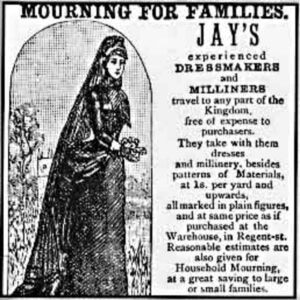

Warehouse advertisement

Jay’s Mourning Warehouse was conceived as a one-stop bereavement department store. It sold fabric and ready-made garments of every type and size for all stages of mourning but could also dispatch skilled dressmakers to one’s home for personal outfitting, advertising: “Ladies living at a distance may be supplied at their own Residence” with an army of “experienced dressmakers and milliners, ready to travel to any part of the kingdom, free of expense to purchasers, when the emergencies of sudden or unexpected Mourning require the immediate execution of mourning orders.”

These traveling salesmen of sorts would be armed with fabric swatches and an array of ready-made dresses and hats. For other circumstances, there was a catalog service available with several illustrated plates of dresses and accessories; Victorians loved catalogs, and Jay’s catalogs were very much the arbiter of grief.

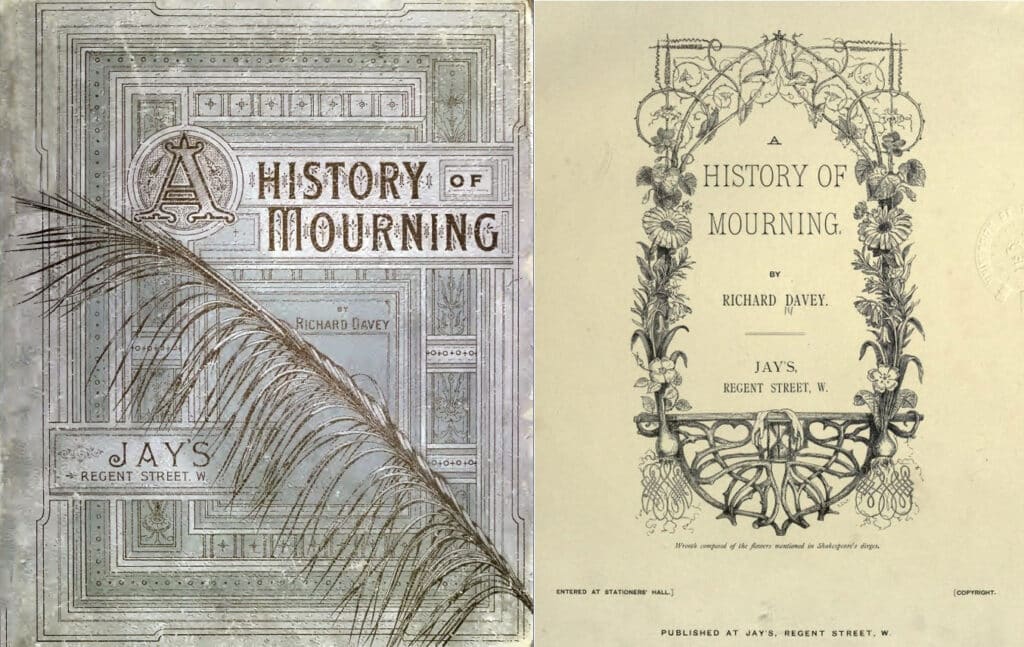

Jay also commissioned writer Richard Davey to publish the definitive etiquette handbook on mourning to assist their customers in mourning appropriately. A History of Mourning was a large and elaborately illustrated tome documenting mourning rituals from ancient Egypt to the “present” day. Davey explored not only clothing but funeral rites and the mourning performances of the

aristocracy throughout time. If the Victorian reader was unsure as to mourning policy and guidelines, Davey helpfully included a series of notices toward the back of the book which offered detailed information as to what to wear, depending on your stage of grief.

As Jay’s business grew, so did the quality and unique nature of its attributes, as the firm wrote in an 1860s advertisement: “Of late years the business and enterprise of this firm has enormously increased, and it includes not only all that is necessary for mourning, but also departments devoted to dresses of a more general description, although the colors are confined to such as could be worn for either full or half mourning.”

Although known for mourning dress and accessories, one of the most important departments of the business was “funeral furnishing.” Jay’s provided its customers with the complete furnishing of funerals, “supplying everything essential to propriety and decorum,” including an efficient staff dispatched to the mourner’s home to take complete charge and “conduct all the arrangements from first to last, without the slightest trouble to the bereaved.” Their ads touted that “reasonable estimates are also given for Household Mourning, at a great savings to large and small families.”

Jay’s flourished well into the 20th century with upwards of six hundred hands in their service, including showroom and counter assistants, clerks, and workpeople engaged in the “making-up” departments. At its height, it took up an enormous chunk of Regent Street, spanning several large units, and was doing a brisk export business to both France and the United States. Jay’s famously dressed Queen Victoria for mourning after the death of her husband and for the following 40 years of her life, during which she remained in mourning dress and set a national trend.

The Marketing of Mourning

Advertising in the late 19th century, both in Europe and in America, consisted primarily of advertorials, which provided space for the business owner to talk directly and in detail about their offerings to their patrons. This form of marketing was particularly effective for mourning warehouses. As death was a more common and sudden occurrence at the time of pre-20th century modern medicine, sudden mourning was a shared experience across all classes. Yet, many had the desire but did not have the background or understanding of how to mourn in Victorian fashion, especially in the United States.

In their vulnerable state, modest mourners in particular were easily overwhelmed by the requirements, items, and accessories associated with Victorian mourning, and could be talked into buying multiple or unnecessary items to prevent the mistake of acquiring the wrong items or selecting the wrong colors. It was not uncommon for women and many families to go into debt or become homeless during the Victorian Era by observing the fashion of mourning.

Mourning warehouse advertising spoke directly to that consumer vulnerability, assuring readers that everything they needed and needed to know when the time came could be found in their establishment and with their help. This was a comforting message, especially given the premium placed on socially appropriate mourning during the Victorian Era on those with limited financial resources but aspiring to put on a public show. That guidance was also particularly helpful to Americans still holding on to “all things English aristocracy” in an attempt to maintain a similar social order in this country.

Mourning in America

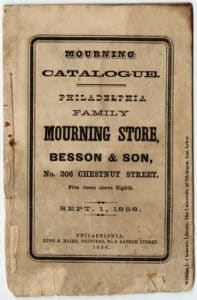

Mourning warehouses also became popular businesses in America in the second half of the 19th century. Civil War widows needed a place they could go to dress their grief suitably. Ordering from London-based mourning warehouses and waiting for the return of goods was not practical or sustainable in a country that was becoming increasingly self-reliant. Businesses such as Besson & Son in Philadelphia and Jackson’s Mourning Warehouse in New York City sprung up to meet this urgent domestic demand, modeling their establishments after Jay’s and other prosperous London mourning houses, as their advertising shows.

Jackson’s Mourning Warehouse, located at No. 777 Broadway, between Ninth and Tenth streets, offered “the most complete stock of mourning goods … of the latest style.” Jackson’s advertorials promoted the Establishment’s latest seasonal fashions, affordability, and convenience, all compelling reasons for American consumers to shop domestically rather than ordering and importing mourning fabric and mourning ware from overseas. They regularly advertised their wares in The New York Times.

In an April 28, 1886, advertorial in The New York Times, Jackson’s announced that many specialties in dress goods for summer wear were now on hand. “Among the silk fabrics, India pongees are especially noticeable.” A pongee is a soft and typically unbleached type of Chinese plain-woven fabric, originally made from threads of raw silk, today made with cotton.

An April 18, 1888, advertisement in The New York Times invited patrons to pay “special attention to the big display in the cloak and suit departments, the gems in millinery, to the grey and second mourning goods, pongees and plain stripes, and incidentally, it may be mentioned that there is a large assortment of sateens and zephyr ginghams in the cotton department.” It then went on to provide pricing on a range of ready-made mourning garments and accessories and fabric by the yard. The advertisement concluded that “there is nothing that a lady in mourning can desire that is not to be found in this old and well-known store.”

In their 1856 catalog, Besson and Son’s Mourning Store of Philadelphia assured prospective buyers of the quality of their black goods, promising only “what is of the proper shade of black” in their “Crape Grenadines, Balzerines, Baryadere Bareges, and Black Bareges.” An October 21, 1862, ad from Besson & Son, Philadelphia, in The North American, provides an extensive list of the assortment of mourning goods it sells, from Black Dress Goods to Shawls, Silks, and accessories, and emphasizes that it also offers “a large stock of second mourning dress goods … of the latest styles and at reasonable prices.”

Mourning in the Post-Victorian Era

The fashion of and passion for mourning changed in the decades following Queen Victoria’s death in 1901 as public interest in holding and funding elaborate funerals and adhering to a strict and complex set of Victorian Era mourning rituals, waned. A new era of mourners could now look to new sources and resources and mourn on their own terms, in their own fashion. This shift in the 20th-century culture of mourning ultimately led to the demise of mourning warehouses; its value proposition absorbed and replaced by other types of businesses and retailers.

The fast-rising industry of funeral homes (by 1920, there were around 24,469 funeral homes in the United States, showing a 100% growth in less than 80 years) and the profession of “Undertaker” could now coordinate and handle all aspects of a burial, services once provided by a mourning warehouse. Mourning appropriate ready-to-wear black dresses and accessories could now be purchased in the mourning departments of better department stores everywhere or ordered through a catalog.

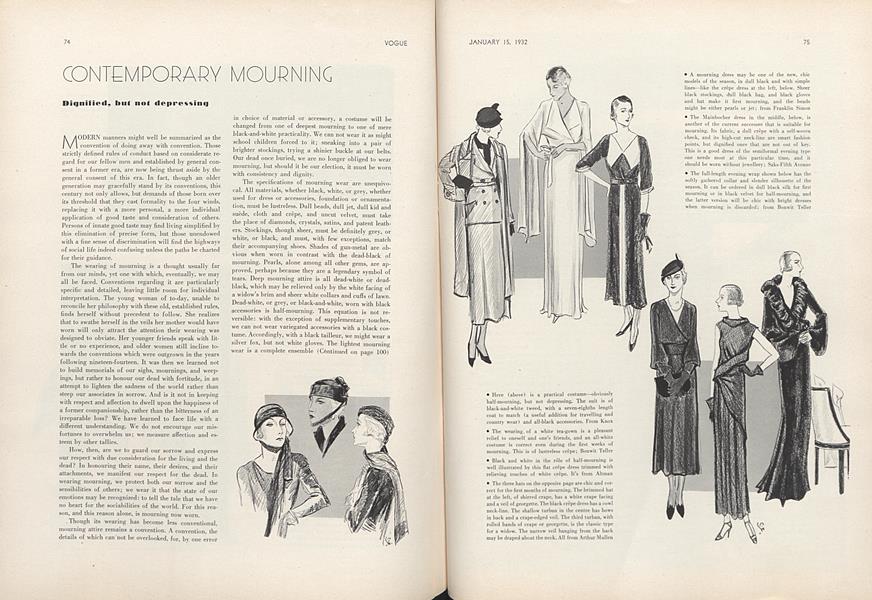

Where once only royalty set mourning style, trends, and requirements, the stock of which drove the inventory of a mourning warehouse, now ladies’ magazines were the arbiters of fashionable mourning. In 1932, Vogue provided a multi-page illustrated article to share and show what fashionable mourning—to be found in better ladies’ shops—looked like.

These were not your grandmother’s widow’s weeds.

Related posts: