“At eBay Prices” – Business of Doing Business – The Journal of Antiques and Collectibles –

By Ed Welch

The term “at eBay prices” has become synonymous with the term “discount retailing.” Discount retailing works well for large retail sellers, like Wal-Mart, because they can order a huge supply of popular items at a lower price to meet the demands of their customers. Discount retailing does not work for antique and art businesses, where the supply of merchandise is almost always limited. Generally speaking, antique dealers cannot sell at a low price and expect to make money with volume.

But the term “at eBay prices” belies that fact. An Aug. 6 article by Kevin Manley in USA Today details how AT&T, Verizon Communications, and SBC Communications – known as the Big Three – want MCI (now in bankruptcy) removed completely as a provider of telephone and telecommunication services. The article states that the Big Three are after MCI for two reasons. First, there will be one less competitor in the telecommunications marketplace. Second, MCI’s valuable assets can be bought by the Big Three “at eBay prices.” When major corporations and market analyzers deem “eBay prices” to be synonymous with “cheap” and “bargain basement” rates, a small business owner should take notice.

Evidence shows that the term is well-founded. Tias.com, a company that provides electronic storefronts (eStores) and an interface for their users to sell on eBay, analyzed 18,000 items sold by their clients with the on-line auction house. The study revealed that eBay prices were down 39 percent compared to the previous year. At the same time, the number of items posted by their members had increased 63 percent. The study showed that their dealers worked much harder finding, cleaning, posting, and shipping items sold on eBay. And, they were doing all this work for much less money. (More about this study is available at Tias.com and Auctionbytes.com.)

At one time, I sold thousands of items on eBay for reasonable and, every now and then, extremely high prices. I still sell on eBay, but only low-end items. For example, I recently purchased 5,000 books for $800 (16 cents each). I posted these books on eBay with no reserve and a starting price of $4. My overhead was about 30 cents each. About half of the books sold. Of that half, about 80 percent sold for the starting bid of $4. The other 20 percent brought between $10 and $60 each. The other half of the books that did not sell on eBay were put on the market at several local auctions. The average selling price was $1 per book.

A quick review of my expenses and income is revealing. My costs included : the purchase price (16 cents), eBay sellers fee (30 cents), local auctions sellers fee (20 cents), and state and federal income taxes (11 cents). My 16-cent book, having failed to sell on eBay, now cost me 77 cents. Therefore, I made 23 cents for each book sold at local auction while making much more per book on eBay. Obviously, for this low-end lot of books, eBay is a much better marketplace.

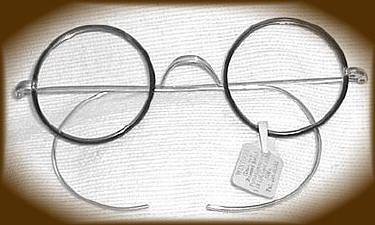

Let’s take another case in point. As an experiment for this article, I sold on eBay a pair of Windsor-style gold-filled eyeglasses that I had purchased at Brimfield for $35. The eyeglasses were old warehouse stock from the 1920s and were never used. They still retained their original identification and price sticker. Six people placed bids on these eyeglasses, and they sold for $20.50. I specialize in antique and vintage eyeglasses and have nearly 20,000 pair in stock. I commonly sell Windsor style eyeglasses between $65 and $85 each. The eBay buyer got a real bargain.

But that has been the trend. Five years ago, a similar Windsor frame would sell for between $85 and $125 on eBay. Three years ago that frame would sell for between $50 and $60 on eBay. Today, the selling price is about $20. Obviously, a dealer is much better off selling such frames at Brimfield. In fact, if the person who bought the frames resells them at Brimfield, I will gladly buy them again for $35.

There are many reasons for the decline of selling prices at the virtual auction giant. eBay, itself, is a major factor, because it has two practices that are, in my opinion, “anti-seller.” First, all the cost is placed on the seller. eBay buyers have no financial incentive in keeping eBay viable. Second, it allows end-of-auction sniping. eBay actually penalizes sellers by encouraging this form of bidding, which prevents more than one interested buyer from bidding at the end of the bidding cycle. It is almost the same as an auctioneer in a live on-site auction accepting only the first bid. It makes no sense to me that eBay receives 100 percent of its income from sellers, but at the same time it conducts its auctions in such a manner as to be detrimental to the seller.

Some marketplace watchers have blamed the fall in eBay prices on a glut of goods. This is certainly not the case for antiques, which by their very nature are in limited supply. I will agree that a glut of common mass-produced collectibles does place a downward pressure on auction prices. However, even mass-produced collectibles such as Depression glass and Roseville are limited in number. In addition, collectibles have never been a stable commodity in the antiques marketplace because prices are subject to the whims and fantasies of dealers and collectors.

Prices can soar to new heights – then plummet to new lows – in a matter of weeks or months. The eBay market for collectibles simply reflects this lack of stability.

Another possible factor in the decline of Internet auction prices has nothing to do with eBay. Historically, selling prices have always risen when antiques and collectibles are introduced to a new method of selling. When group shops began to appear in the late 1960s, prices for antiques and collectibles doubled, tripled, and soared to new highs. For example, when the first group shop in Maine, called Bo-Mar Hall, opened in the fall of 1972, I was a wholesale dealer specializing in furniture. The price for an oak commode had for a long time been $12.50 wholesale.

The oak commodes I offered for sale at Bo-Mar Hall would fetch $36. But that did not last. Prices at group shops eventually stabilized due in part to price guides, trade papers, and the over-abundance of group shops.

When many antique “shows and sales” changed their format in the late 1960s, the price of antiques and collectibles again increased. Early antique “shows and sales” were places for collectors to show off their collections. Selling was an afterthought.

In fact, many booths had nothing for sale. Furthermore, items that were for sale included duplicates and less-than-perfect pieces. I displayed at one of these early “selling shows,” as we then called them, in the fall of 1968. I sold so well that I was able to buy a 1968 Chevrolet four-wheel-drive pickup complete with snowplow – and pay cash for it. But prices realized at shows have stabilized over the years for the same reasons that prices have stabilized in group shops.

When the Internet became available to the public in early 1991, I began selling antiques by placing them on bulletin boards and in classified ads. There was no World Wide Web (www) at that time; all sites on the Internet were FTP. When the World Wide Web, and later eBay, came to the Internet, I was ready to take full advantage of both. Prices realized on the Internet and later on eBay were so high that I would be embarrassed to quote them here. But selling on the Internet in the first few years was difficult. Photographs had to be sent by snail mail. Payment had to be made by check, and shipping was a nightmare. The credit card company that I had used for years dropped me like a hot potato the first time I made a sale for $3,500. They told me that Internet selling was too risky for any credit card company. I had a difficult time finding another credit card company that would accept payment for merchandise sold on the Internet. The only reason that I and other early Internet sellers persisted was the high profits.

There were other challenges in the first two years of eBay that are unimaginable now. The only time of day that it was possible for sellers in Maine to post items for sale was between 2 and 4 a.m. because Internet connections were slow and telephone line capacity was not adequate to handle regular telephone service as well as the Internet. To keep things on eBay, I had to get up at 1:30 a.m., post between 2 and 4 a.m., and then go back to bed for a couple of hours. Had the profits not been so high, I would not have done this.

Historically speaking, when prices leveled out at group shops and antique shows, they did not decline. Today, prices on eBay have not only leveled, they have declined. But eBay is following an established pattern in the antique marketplace: a new selling method is introduced, and prices rise. As more people rush to take advantage of these new high prices, prices level out. Usually, the first people to use a new selling method make the most money, so looking at new trends is critical.

The next new method of selling antiques is the self owned and self maintained eBusiness selling site. For the adventurous and the aggressive seller, that eBusiness site must be a dot.com. For the less adventurous, the hobbyist, and the part-time dealer, that eBusiness site can be an eStore.

Do you know the difference between an eBusiness site and an eStore? Do you know the advantages and disadvantages of each method? Hundreds of millions of dollars in antique sales on the Internet are up for grabs in the next five years. If you want a piece of this pie, invest your time and money in learning how to create, build, and maintain an eBusiness site or an eStore.

-

- Assign a menu in Theme Options > Menus WooCommerce not Found

Related posts: